Perfect Tribute To Indo-Iran Ties

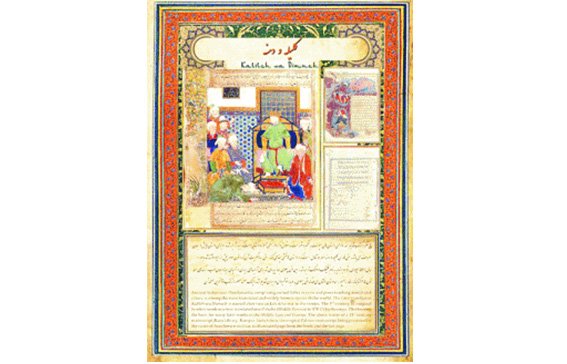

The facsimile reproduction of Kalila va Dimna, calligraphed by Sultan Muhammad in the Timurid period and preserved at the Raza Library in Rampur, is a homage to the ‘cousin cultures’ of the two countries, writes Professor Lokesh Chandra

The facsimile reproduction of Kalila va Dimna, calligraphed by Sultan Muhammad in the Timurid period and preserved at the Raza Library in Rampur, is a homage to the ‘cousin cultures’ of the two countries, writes Professor Lokesh Chandra

This facsimile edition of the Kalila va Dimna is a tribute to the cultural interflow between India and Iran over millennia, attested by the nexus of the Rigvedic hymns and Gathas of Zarathushtra, coming down to the reign of Akbar, who introduced Persian as the language of administration in India which continued till the middle of the 19th century under the East India Company. The Persian version of the Kalila va Dimna entitled Anwar-i Suhayli had the historic destiny of being the textbook for learning Persian to run the Government of the day.

India and Iran are the “we together” in the glory of language, with similar divinities in classical times, the Gathas and Vedic hymns with mindprints of common essence, Iranians of Parthia and Sogdiana translating Buddhist Sutras into Chinese, Iranian doctors curing Samba, the son of Lord Krishna, or Jivaka, the physician of Lord Buddha, studying under “white clad medicos”: Endless sharings throbbing with harmony.

The dynasty of Sasan were hereditary priests of a Zoroastrian temple. The grandson of Sasan Ardashir I defeated the Parthian king Ardavan I in 224 AD and founded the Sasanian dynasty. He advised his son Shapur I (ruled 241-72): “Know that faith and kingship are brothers, one cannot survive without the other. Faith is the foundation of a kingdom, and the kingdom defends the faith”.

There is a similar saying in Sanskrit: “Dharmo rakshati; Dharmo hato hanti.” He conquered the Kushan kingdom of Bactria, and the Sasanian kings came close to India. Shapur I ordered the collection and translation of religious, astronomical, medical and philosophical texts from the Byzantine Empire and from India. The books of moral precepts (andarz) were an important genre in Sasanian literature.

Pahlavi inscriptions of Kartir, who was a dominant figure in the Zoroastrian church in the reign ot-Bahram II (276-293), refer to Buddhists and Brahmans in Iran.

King Khusrau I (Susravas in Sanskrit) came to the throne in 531 and had a four decade-long rule till 579. His reign is famous for the final redaction of the 21 divisions of the Avesta, the vitalisation of the Iranian state, the blossoming of art and literature, and the translation of many Indian works into Pahlavi.

His epithet was Anushirvan “of immortal soul”. He was an enlightened monarch. When Justinian closed Plato’s Academy at Athens, which had been a centre of Greek culture and philosophy, some philosophers took refuge at his court. Greek and Sanskrit works began to be translated into Pahlavi.

Several collections of andarz or “advice” or “mirrors for princes” from his period have survived. The Pahlavi adaptation of the Panchatantra was the prime mirror for princes and commoners. The Avestan alphabet is also attributed to his reign. The pomp and glory of his reign can be seen in the immense size of the aivan or central arch of Taq-i Kisra in Ctesiphon.

Wisdom (andarz) literature was cultivated by writers, priests and royalty as ethical and practical precepts, maxims and epigrams. The Sasanians considered history and myth as validating social and political ideals and institutions. Visnusarma states in the opening of the first book of the Panchatantra that it is a collection of the essence of all the arthasastras, composed as delightful lessons in polity. It was designed to teach polity and statecraft to young princes in the form of fascinating stories and fables. With a penetrating insight into human affairs and a sense of humour, it reveals social consciousness in its mobility and treachery, in its maturity and worldly wisdom.

King Khusrau Anushirvan sent his physician Burzoe to India to get books on royal governance, particularly, the Panchatantra. Burzoe translated the Sanskrit Panchatantra into Pahlavi and expanded it from other Indian sources: Its chapters 11-13 are from the Mahabharata 12.138, 139, 111, and the other five chapters have to be traced in Indian sources. This Pahlavi translation is lost.

Syriac version: The Pahlavi was translated into Syriac by Periodeut Bud in 570, and it survives in manuscripts.

Ibn al-Muqaffa translated the Pahlavi into Arabic as a stylistic work of art intended for literary connoisseurs. Its stories became very popular and that led to frequent changes in its wording. The numerous quotations in Ibn Qutayba no longer reproduce Al-Muqaffa’s text word to word. An edition for school use was done as late as 1910.

Arabic version: It was put into Arabic verse three times — the first version was by al-Laqiki, a contemporary of Al-Muqaffa. It has been lost. The second verification was by Ibn al-Habbariya in 1100 with the help of both versions, in elegant and flowing language. The third versification was by Abd al-Mumin completed in 80 days on November 15, 1242.

A Syriac priest translated Al-Muqaffa’s text again into Syriac and endeavoured to give it a Christian tinge.

Poet Rudhaki (died 916) put the book into Persian verse, but only 16 verses have survived as quotations in Asadi’s Lughat-i Furs.

Nasr Allah reproduced Al-Muqaffa’s work in all rhetorical adornments of prose in 1144. On its basis Al-Tusi Qani composed a metrical version in the 13th Century. In 1504, Kashifi gave a new version in a more florid style and it had unparalleled success. He called it Anwar-i Suhayli in honour of the minister of the king in whose court he was. It was printed in England in 1836 as a text book for the examination of English officials in India in Persian. It was translated into several Indian languages.

It was translated twice into Eastern Turki, into old Ottoman Turkish, Ethiopic, Hebrew, Greek, Malay and several European languages. The Mongol translation was read by the Yiian Emperor Mongke Khan (ruled 1251-58) as a treatise on political theory and practice.

Kalila va Dimna inspired Iranian artists of the pre and post-Mongol schools and there is a large number of illustrated manuscripts.

Kalila va Dimna led to numerous translations into European languages: Greek (11th Century), Hebrew (12th Century), Latin (1480), German (1483), Italian (1563). Its distant echo is to be found in the charming fables in La Fontaine as late as the 17th Century. Ph Wolff calls it a book “that inspired the entire mankind and was held in reverence by kings and princes”.

The present facsimile reproduction of the manuscript, calligraphed by Sultan Muhammad in the Timurid period and preserved in the Raza Library at Rampur, Uttar Pradesh, is a homage to the “cousin cultures” of India and Iran. It reminds of Emperor Akbar’s desire to come close to the Iranians, for which he prepared the ground for Iranian intellectuals to flourish in India. Poet Salim Tehrani went so far as to say: “Henna did not acquire colour till it came to India.”

Humankind has to envision the emergence of a new awareness which will make life harmonious within ourselves and without with the world, to shake off the dust of minds. Humans have to wash their inkstone of its profane words, leaving body and soul transparently pure. As poet Rumi says:

“You dance inside my chest,Where no one sees you. But sometimes, I do,And that sight becomes this art.”

The writer is President, ICCR

Published on Daily Pioneer