Palkhivala and The Constitution of India

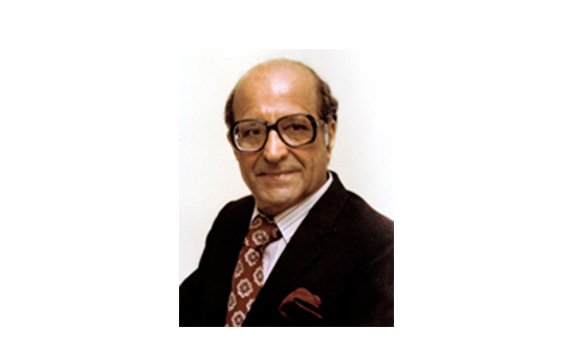

On 16-1-1920 was born a child in Bombay whom his parents christened Nanabhoy. It was not an earth-shattering event at that time. In later years, he was known as Nani Palkhivala—a household name, not only amongst lawyers, but throughout the length and breadth of our country. What was the constitution of this man who became an authority and a guardian of our Constitution in later years? What was his background?

On 16-1-1920 was born a child in Bombay whom his parents christened Nanabhoy. It was not an earth-shattering event at that time. In later years, he was known as Nani Palkhivala—a household name, not only amongst lawyers, but throughout the length and breadth of our country. What was the constitution of this man who became an authority and a guardian of our Constitution in later years? What was his background?

Physically he was not impressive. A young, slim boy measuring about 5 feet 7 inches in height and not having many kilos to carry. Nani Palkhivala was not born with a silver spoon in his mouth. He hailed from a humble Parsi middle-class working family. His ancestors were in the profession of making and fixing “palkhis,” namely, palanquins, to be fitted to horse carriages of those times. Hence the surname Palkhivala, which like many Parsi surnames, is associated with a particular calling or profession.

Nani Palkhivala’s schooling was in Master’s Tutorial High School in Bombay. He was a brilliant student and did extremely well despite his initial handicap of stammering which he overcame by sheer willpower. After matriculation he joined St. Xavier’s College, Bombay and completed his MA in English Literature. In younger days, he did take to music and played the violin reasonably well. But the spell of Apollo was short-lived. Music was not one of his passions in later life.

Palkhivala applied for a Lecturer’s post at Bombay University. To his surprise and regret, a Parsee girl was appointed to the post. With admission to most other courses closed, he enrolled at Government Law College, Bombay. This is one instance how destiny plays a role in one’s life. Had Palkhivala got the Lecturer’s post, we would have had a brilliant Professor but the world of law and public life would have been a loser. Nani was eternally grateful to the young lady Professor and treated her to a dinner for several years. Nani had the good fortune of joining the chambers of the legendary Sir Jamshedji Kanga in Bombay in 1944. He had no godfathers in the profession. His rise at the Bar was meteoric. Within a couple of years of joining the profession, he was briefed in every important matter in the High Court. He was the darling of the young members of the Bar who would throng the court to listen to his arguments. The first case of constitutional significance in which he appeared in the Bombay High Court was Fram Nusserwanji Balsara v. State of Bombay1 in which various provisions of the Bombay Prohibition Act were challenged. He was the juniormost counsel in the case which was argued by Sir Noshirwan Engineer. Some students of Government Law College, Bombay and I had bunked our classes and gone to the High Court to witness the proceedings. I distinctly remember Nani sitting at the end of the row and passing on written chits to the other counsel in the case who along with Sir Engineer were G.N. Joshi and R.J. Kolah.

It was not long before Palkhivala started arguing cases himself. The validity of the Administration of Evacuee Property Act and the Bombay Land Requisition Act were challenged. Nani was in the forefront of the legal challenges to these Acts which, however, were repelled by the Bombay High Court. Those familiar with the legal profession know that a lawyer often makes his mark not only by the cases he wins but by the quality of his performance in cases where the ultimate result is not favourable. Abdul Majid2 and Heman Alreja3 were two such cases in which Nani distinguished himself in 1950-51.

Another important case which Nani argued was the famous RMDC case4 which involved the question whether solution of a crossword puzzle in question depended on the exercise of skill or whether it was a lottery and chance predominated. A case of constitutional significance which Palkhivala argued in 1954 and won before the Bombay High Court was the one concerning the interpretation of Article 29(2) and Article 30 of the Constitution. It related to the right of Anglo-Indian schools regarding admission of students in schools teaching through the medium of English. The impugned circular issued by the State of Bombay was struck down by a Division Bench of the Bombay High Court presided over by that great Chief Justice, M.C. Chagla. Chagla was Nani’s most favourite Judge. He considered Chagla a great Judge whose burning desire was to do real justice and, whose judgments in Nani’s words, “had no dark nooks or misty crannies”.

The State of Bombay carried the matter to the Supreme Court which upheld the judgment of the Bombay High Court and ruled that the impugned circular violated the fundamental right guaranteed under Article 29(2) of the Constitution. Nani argued the case brilliantly before the Supreme Court. He was hardly ten years at the Bar.

Despite his busy practice, Nani devoted time to teaching law to students and was a part-time Lecturer at Government Law College, Bombay. He endeared himself to students by his clear exposition of the subject—always with a dash of humour and wit. (At that time he was lecturing on the Evidence Act.) His was one class that I and other students did not bunk. Indeed, we all wished that his lecture would go on beyond the allotted time. Justice Chandrachud, who was also a part-time Lecturer, has written in his piece in a Marathi daily that he and Nani shared a horse-driven Victoria to reach the Law College since they could not afford a taxi.

Nani’s contribution to the development of our constitutional jurisprudence commenced with his appearances in the Supreme Court in cases involving interpretation of the Constitution.

In Bhanji Munji5, the validity of the Bombay Land Requisition Act was challenged. The Supreme Court applied the Gopalan6 doctrine, namely, that the freedoms relating to the person of a citizen guaranteed by Article 19 assume the existence of a free citizen and can no longer be enjoyed if a citizen were deprived of his liberty by the law of preventive or punitive detention. Consequently, the Court ruled that when there is a substantially total deprivation of property which is already held and enjoyed, Article 19(1)(f) is excluded and is not applicable. One must then turn to Article 31 and see how far that is justified. Despite Palkhivala’s forceful advocacy, the Supreme Court refused to test the validity of the Bombay Land Requisition Act on the touchstone of Article 19(1)(f). That was in 1954.

Later in February 1970, in Bank Nationalisation case7 this legal heresy which had a restrictive, indeed a pernicious effect, on the development of constitutional law was given a long-awaited burial. The Court held that Article 19(1)(f) and Article 31(2) were not mutually exclusive.

This to my mind was Palkhivala’s signal contribution to the development of our Constitution by persuading the Supreme Court to remove the distortions that had crept in because of the earlier judgments. The irony is that Gopalan6, a case relating to the personal liberty of a Communist leader, was overruled in a case relating to property rights in the context of bank nationalisation.

Privy Purse case8 was another of Palkhivala’s achievements. He was appalled by the breach of faith by the Government of India by passing a midnight executive order derecognizing the Princes. The pledge given to the Princes by Sardar Patel in the Constituent Assembly when the Privy Purse provisions were enacted was flagrantly dishonoured. He felt that the action of the Government of India apart from being unconstitutional was in breach of constitutional morality. He firmly believed that:

“The survival of our democracy and the unity and integrity of the nation depend upon the realisation that constitutional morality is no less essential than constitutional legality. Dharma (righteousness; sense of public duty or virtue) lives in the hearts of public men; when it dies there, no Constitution, no law, no amendment, can save it.”

Freedom of expression and freedom of the press are the cornerstones of democracy, the Ark of the Covenant of our Constitution. A disingenuous attempt was made to stifle press freedom through the machinery of the import control regulations by imposing severe restrictions on the import of newsprint. Bennett Coleman, amongst other newspapers, challenged the import control policy.9 Nani was briefed. I was privileged to be his junior. Incidentally, Palkhivala was a Director of the national daily, Statesman, which fact also accounts for his deep attachment to press freedom. Nani’s performance was superb. The propositions he enunciated were a model of clarity, marked by elegance of language. Some of them are reflected in the majority judgment of Justice A.N. Ray. For example, the passage: “Newsprint does not stand on the same footing as steel. Steel will yield products of steel. Newsprint will manifest whatever is thought of by man”10 It is a pity that counsel’s arguments in important cases are not reported in the law reports. The Court struck down the restrictions. This judgment is another instance of the generous protection accorded to press freedom by our judiciary.

Rights of the minorities figured prominently in the Constituent Assembly Debates. Minority rights are indeed human rights and have been rightly guaranteed as fundamental rights in our Constitution. The minorities attached great importance to the freedom of religion and the right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice. They gave up their demand for separate electorates in view of the guarantee of these rights as fundamental rights and their guardianship and protection by the Supreme Court. The fears of the minorities were dispelled, in the words of Rev. Jerome D’Souza, who represented the Indian Christian community, by

“the completeness, the generosity, the thoroughness with which individual rights have been safeguarded in the section of our Constitution devoted to fundamental rights, the way in which these fundamental rights were placed under the power and jurisdiction of the Supreme Judicature and the spirit in which those provisions were passed by this House.”

State legislation encroaching upon the right of minority educational institutions became frequent. That led to St. Xavier’s College challenging the legislation in the Supreme Court. As you may be aware, St. Xavier’s College was Nani’s alma mater. It was mine as well. We both appeared in the Supreme Court. We did not charge any fees. The crux of the matter was the autonomy of the educational institutions and what were the limits of governmental interference especially in the matter of appointment and dismissal of teachers and admission of students of the minority community. There was no dispute that the right to administer did not comprehend the right to maladminister. But where did administration of educational institutions end and maladministration begin? Nani eloquently and movingly expounded the legal position to the nine-Judge Bench. The majority judgment11 upholding the right of the minorities is a substantial contribution to our constitutional jurisprudence. It is heartening that the recent eleven-Judge Bench judgment12 has not departed from the salutary principles laid down in St. Xavier’s College case11.

No account of Palkhivala would be complete without mention of his magnum opus, The Law and Practice of Income Tax. It is not customary to cite textbooks of living authors. Palkhivala’s treatise on income tax was an exception. Lawyers, judges, members of the Income Tax Tribunal and income tax practitioners regarded the book as their Bible and invariably relied upon it. The work has secured national and international recognition. The first edition of the book was published in 1950 when Palkhivala was about 30 years old. Sir Jamshedji whose name appears first in the table of the book gracefully acknowledged that the credit belonged to Palkhivala.

It seems that there was something in Nani’s genes which attracted him to the law of taxation. His talent in expounding the subject was matched by his genius in explaining the intricacies of the Budget to thousands of his listeners. His famous Annual Budget speeches had humble beginnings in 1958 in a small hall of an old hotel called Green Hotel in Bombay. He spoke without notes and reeled off facts and figures from memory for over an hour keeping his audience in rapt attention.

The audience in these meetings was drawn from industrialists, lawyers, businessmen and the common individual. Nani’s speeches were fascinating for their brevity and clarity. His Budget speeches became so popular throughout India and the audience for them grew so large that bigger halls and later the Brabourne stadium in Bombay had to be booked to keep pace with the demand of an audience of over 20,000. It was aptly said that in those days that there were two Budget speeches, one by the Finance Minister and the other by Nani Palkhivala, and Palkhivala’s speech was undoubtedly the more popular and sought after. It was a phenomenon, which could come only from a genius in the art of communicating.

Palkhivala had deep respect, indeed reverence for the Constitution. He realised the importance of preserving the cardinal values of the Constitution, its basic and essential features. His favourite quotation was the statement of Joseph Story, the great American jurist, who said:

“The Constitution has been reared for immortality, if the work of man may justly aspire to such a title. It may, nevertheless, perish in an hour by the folly, or corruption, or negligence of its only keepers, THE PEOPLE.”

As you may be aware these words of Story were quoted by Sachchidananda Sinha in his inaugural address, as Provisional Chairman, to the Constituent Assembly on 9-12-1946.

Palkhivala believed that a Constitution is intended not merely to provide for the exigencies of the moment but to endure over the ages. He urged that we should get accustomed to a spacious view of the great instrument because “the Constitution was meant to impart such a momentum to the living spirit of the rule of law that democracy and civil liberty may survive in India beyond our own times and in the days when our place will know us no more”. He pointed out that our original Constitution provided for stability without stagnation and growth without destruction of human values. He lamented that the recent amendments had only achieved stagnation without stability and destruction of human values without growth. Palkhivala did not at all believe that a Constitution is unamendable or cannot be changed. He shared the thinking of Thomas Jefferson who said:

“Some men look at constitutions with sanctimonious reverence and deem them like the Ark of the Covenant too sacred to be touched. They ascribe to the men of the preceding age a wisdom more than human and suppose what they did to be beyond amendment…. I am certainly not an advocate for frequent and untried changes in laws and Constitution … but I know that the laws and institutions must go hand in hand with the progress of human mind…. As new discoveries are made, new truths discovered and manners and opinions change, with the change of circumstances, institutions must advance also and keep pace with the times.”

Palkhivala appreciated the wise words of Pandit Nehru who expressed the same thought in felicitous language.

“A constitution which is unchanging and static, it does not matter how good it is, how perfect it is, is a constitution that has past its use. It is in its old age already and gradually approaching its death. A constitution to be living must be growing; must be adaptable; must be flexible; must be changeable … as society changes, as conditions change, we amend it in the proper way.”

What outraged Palkhivala was the tinkering with the Constitution by the politicians, its frequent amendment as if it were a Municipal Licensing Act or the Drugs Act, the failure to preserve the integrity of our Constitution against many hasty and ill-considered changes, the fruits of passion and ignorance. His firm belief was that Parliament’s amending power is not absolute, the amending power is subject to inherent and implied limitations which do not permit Parliament to destroy any of the essential features of the Constitution and thereby damage the basic structure of the Constitution.

The zenith of Palkhivala’s fame and forensic success was in persuading the Supreme Court to accept the basic structure doctrine which it did by a majority in Kesavananda Bharati case13 I vividly remember the early morning conferences the two of us had those days in his room at Oberoi Hotel. Both of us were in our pyjamas. At one such conference, I nervously suggested the argument about inherent limitations on the amending power based on certain articles which I had read in the US law journals. He grasped the point, but was not quite convinced. A few hours later in the Supreme Court, he expounded the doctrine brilliantly. The labour and efforts which were put in the case were tremendous. The range of our research was far and wide. I remember the volumes of the Constituent Assembly Debates which I went through in order to prepare a “short note” for Nani. He did not like long and verbose submissions. To my mind Kesavananda Bharati was Palkhivala’s greatest contribution to our constitutional jurisprudence. The judgment has been a salutary check on Parliament’s tendency to ride roughshod over fundamental rights and its insatiable appetite to encroach upon fundamental rights. You may be interested to know that the Bangladesh Supreme Court has followed the Supreme Court judgment in Kesavananda Bharati and struck down a constitutional amendment.

Nani, however, was at his forensic best in his arguments before the Bench which was specially constituted to reconsider Kesavananda Bharati. In the words of one of the Judges on the Bench “the heights of eloquence to which Palkhivala had risen have seldom been equalled and never been surpassed in the history of the Supreme Court”.14

Decision of the Supreme Court in Minerva Mills15 was another of Nani’s triumphant efforts to prevent the defacement and defilement of our Constitution. His unsurpassable advocacy in the case led the Supreme Court to declare that clause (4) of Article 368 of the Constitution which excludes judicial review of constitutional amendments was unconstitutional.

Nani’s intimate knowledge of taxation law and mastery of constitutional principles were at play in the challenge to the validity of the Expenditure Tax Act. This was one of Nani’s masterly but unsuccessful performances. Will the Supreme Court have time to repent its judgment in Federation of Hotel and Restaurant?16 Only time can tell.

Palkhivala’s forensic skills and ability were not confined to taxation and the Constitution. His knowledge of economics and industrial law and labour legislation were in full display in the case of Premier Automobiles17 which dealt with the issue of fixation of prices for automobiles and also in the case of Jalan Trading18 in which the constitutionality of the Payment of Bonus Act was assailed.

Palkhivala’s range of legal practice is also evident by his appearance and advocacy in Seshammal v. State of T.N.19 which involved the right of archakas in temples. In that case, Palkhivala expounded the rights which flow from the appointment of a priest or an archaka to perform religious functions and the impact and implication of that appointment in relation to the freedom of religion guaranteed by Articles 25 and 26 of the Constitution.

Palkhivala’s forensic achievements were not confined to courts in our country. He represented India in three cases in the international fora. First, before the Special Tribunal in Geneva appointed by the UN to adjudicate upon Pakistan’s claim to enclaves in Kutch. Another was before the International Civil Aviation Organisation at Montreal and later in appeal before the World Court at the Hague when Pakistan claimed the right to fly over India.

There have been lawyers who matched Palkhivala in erudition and legal knowledge. But for sheer advocacy Palkhivala was unsurpassable. Clarity of thought coupled with precision and elegance of expression, impassioned plea for the cause he espoused in the case, excellent court craft and an extraordinary ability to think on his legs rendered him an irresistible force and made him sui generis.

Another instance of destiny playing a part in Palkhivala’s life and career is the offer of the office of the Attorney-General to him. He recounts the incident in his book We the Nation. It is worth reproducing in extenso:

“In 1968, Mr Govinda Menon was the Law Minister in the Congress Government. He pressed me hard to accept the office of the Attorney-General for India. After a great deal of hesitation I agreed. When I was in Delhi I conveyed my acceptance to him, and he told me that the announcement would be made the next day. I was happy that the agonising hours of indecision were over. Sound sleep is one of the blessings I have always enjoyed. That night I went to bed and looked forward to my usual quota of deep slumber. But suddenly and inexplicably, I became wide awake at three o’clock in the morning with the clear conviction, floating like a hook through my consciousness, that my decision was erroneous and that I should reverse it before it was too late. Early in the morning I profusely apologised to the Law Minister for changing my mind. In the years immediately following, it was my privilege to argue on behalf of the citizen, under the same Congress Government, the major cases which have shaped and moulded the constitutional law of India—Bank Nationalisation (1969), Privy Purse (1970), Fundamental Rights (1972-73), among others.”

Palkhivala was offered judgeship of the Supreme Court in the early sixties which he declined possibly for the same reasons which made him decline the office of the Attorney-General for India.

I wish destiny or some other force would have made Nani decline the office of directorship in the House of Tatas. He gave a lot of his time and energy to that excellent business house but which he could have devoted to the legal profession and its improvement and the reform of the legal system.

Palkhivala has received recognition from renowned academics. In the book Working a Democratic Constitution by the eminent Granville Austin, reference to Palkhivala occurs at sixteen pages.

Palkhivala has received citations and honorary degrees of Doctor of Laws from various universities such as Princeton University, New Jersey, and Lawrence University, Wisconsin, Annamalai University, Tamil Nadu University and the University of Mumbai.

The citation he received from Princeton University is worth reproducing as it epitomizes Nani’s basic qualities:

“Defender of constitutional liberties, champion of human rights, he has courageously advanced his conviction that expediency in the name of progress, at the cost of freedom, is no progress at all, but retrogression. Lawyer, teacher, author, and economic developer, he brings to us as Ambassador of India intelligence, good humour, experience, and vision for international understanding….”

All these attainments to which I have referred testify to Palkhivala’s brilliance, his eminence, his versatility, his phenomenal memory. But the quality of greatness which we rightly attribute to him lay in his basic human qualities. The foremost was his willingness to help persons in need without any show or publicity. Let me recount one instance. Dr Badrinath of the famous Shankar Netralaya Hospital in Chennai, was invited for dinner at his home by Nani. After the dinner was over, Nani escorted the doctor to his car and gave him a small envelope saying this was a token contribution for the hospital. When Dr Badrinath later opened the envelope he found in it Nani’s personal cheque for Rs 2 crores. A token contribution indeed!

Let me recount another instance. As a tribute to Jayaprakash Narayan who played an outstanding role in regaining freedom for India after the nightmare of the emergency, Palkhivala founded the Jayaprakash Institute of Human Freedoms. The purpose of the Institute is to strengthen the roots of Indian democracy and to carry on the epoch-making work of that great patriot. A sum of Rs 5,37,000 representing the entire profit from Palkhivala’s 7th Edn. of The Law and Practice of Income Tax was donated to this Institute.

Palkhivala was of the firm view that some minimum qualifications should be prescribed for those who seek election to Parliament. His point was that you need years of training to attend to a boiler or to mind a machine; to supervise a shop floor or to build a bridge, to argue a case in a court of law or to operate upon a human body. But he was shocked that to steer the lives and destinies of millions of our fellow-men, there is no requirement of any education or equipment at all. His favourite quote was Dr Rajendra Prasad’s observation in the Constituent Assembly:

“I would have liked to have some qualification laid down for members of the legislatures. It is anomalous that we should insist upon high qualifications for those who administer or help in administering the law, but none for those who make it except that they are elected.”

He frequently pointed out that it is open to the Prime Minister to select a minority of the Ministers from outside. And the advantage of such a system is that it enables the Prime Minister to have in his Cabinet some of the best talent available in the country. He endorsed Shri Aurobindo’s belief that “State fails in its duties if the ruling class did not represent the best minds of the nation”.

Palkhivala was not attracted by the rituals and the pomp and ceremonies of religion. He believed in and practised the essence of Zoroastrian religion to which he belonged, namely, “Humata, Hukhata, Huvarashta”—good words, good thoughts, good deeds. Shri Aurobindo was his favourite writer and thinker whose writings greatly attracted him. Palkhivala embodied the concept of plain living and high thinking. Success did not go to his head. Fame and fortune did not increase the hat size of the legendary Nani Palkhivala. There was never a trace of arrogance or conceit or pomposity in him.

Another outstanding human quality about Nani was that jealousy, or rather envy, the besetting sin, which cannot countenance the fame and success of others, never consumed him. Holier-than-thou attitude was alien to him. He was not the one to smile and shake your hand and thereafter stab you in the back. Backbiting and denigration of others was unknown to him. Humility and natural modesty were his hallmarks. He had no ego problems. The warmth of his friendship extended to all fellow human beings, whatever be their status in life. He was tender towards the bashful, gentle towards the distant and merciful towards the absurd. Thus Nani fulfilled Cardinal Newman’s definition of a true gentleman. Of Nani, it can be truly said that he walked with Kings yet lost not the common touch.

The greatness of Palkhivala truly lay in his sincerity and commitment to spiritual values which made him a moral force in our public life. The fearlessness with which he spoke out, whichever be the party in power, made him the voice of conscience of the nation. And conscience for Nani was not an alibi but an ally, a constant anchor of his beliefs and actions. He kept the faith and held high the banner of freedom and the rule of law. He fully shared the belief of Justice Frankfurter that “Democracy is always a beckoning goal, not a safe harbour. For freedom is an unremitting endeavour, never a final achievement.”

Regrettably, we live in times when there are no men and women to match our Himalayan peaks, when there is a crisis of moral leadership, when our political system and public life have more hypocrites, wheeler-dealers, schemers and cowards than at any time in our history. Nani was one constant shining star in the dark firmament. His passing away is indeed a real loss to the nation. As I survey the current scene in our public and private life, I am impelled to say: Nani thou shouldst have been living at this hour.

Of late, Palkhivala was deeply upset, indeed depressed, at the catastrophic decline in values in our public life. The onslaught of materialism and its effect on our youth bothered him very much. He was anguished at the deterioration which had set in our institutions. He felt that corruption which in some cases had not spared the judiciary whose independence he had staunchly defended was illustrative of the incredible debasement of our national character.

He lamented that the “Bar is more commercialised than ever before. Today the law is looked upon, not as a learned profession but as a lucrative one.” He stressed the need to educate our lawyers better and not to produce “unethical illiterates in our law colleges, who have no notion of what public good is.” He feared that our country was on a long slide towards darkness and obscurantism with no visible solution and sign of hope. His mission was to launch a movement for the regeneration of values and to maintain and revive idealism in the youth of our country.

Palkhivala was ailing for a long time. It was painful to see that a person so eloquent and articulate was unable to speak or recognize persons except occasionally in a momentary flash. He answered the Inevitable Summons from his Maker on 11-12-2002. Earth received an honoured guest as Palkhivala was laid to rest.

I had known him for fifty years. My first professional association with him was in a matter relating to the Bombay Land Revenue Act in the Bombay High Court. It was an exhilarating experience. His conferences were short and to the point. He appreciated the inputs and research of juniors briefed with him. He treated them with kind consideration and encouraged them. When he was arguing and was on his legs and there was some point or decision I wanted to bring to his attention, it would be by passing a brief note. He would look at it and assimilate it in a few seconds.

I was frequently his guest at his lunches and dinners at home which were marked by complete informality and warm hospitality. In his home in Bombay or in the embassy at Washington he was a wonderful host who had his eyes on all his guests. He and his wife Nergesh, a noble lady who predeceased him, were my guests at my hill-station bungalow at Mahabaleshwar. Alas because of constraints of time, Nani’s inveterate enemy, the duration was just two days.

I am loathe to lend books, because they are seldom returned. The book which I treasure the most are the two of Nani’s books which bear the generous inscription: “For dearest Soli, Who has done so much to uphold the sanctity of the Constitution, Nani, 4-12-1974.”

He was my role model in the profession and a true and dear friend with whom I shared many wonderful times and rich and stimulating experiences. For me, his passing away is a deep personal loss. It has left a void which will be very difficult to fill.

Rajagopalachari rightly said of Palkhivala, “He is God’s gift to us”. Nani Palkhivala’s passing away has indeed left a dent in Indian humanity. Born of the sun he travelled a while towards the sun, and left the vivid air signed with his honour.

Yes friends, Palkhivala has departed from our midst. But he can never leave us, leave our minds and hearts where he is firmly enthroned. And it behoves us all, to carry forward the Palkhivala legacy of truth, goodness and beauty, deriving inspiration from his thoughts, his deeds and the many-splendoured life of this Man for All Seasons, the great NANI PALKHIVALA.

Published on IndianLawyers.com