A marriage of Purim and Persian New Year

Leave it to us, the Iranian Jews, to overdo it. One holiday with our name on it and you are faced with the ultimate Jewish experience in just two days. Purim is dramatic; a holiday that rivals Passover, as it begins with a grand-scale departure and concludes with a triumphant liberation. It brings Yom Kippur, Tisha B’av, Shabbat and Simchat Torah to life when we fast, repent, read and feast.

Indeed, Purim is special for the Iranian Jews in many ways. First and foremost, there is the obvious relationship with the physical place we have called home for more than 2,600 years. Many of Iranian Jews have had the privilege of visiting the tomb of Esther in the Iranian city of Hamedan (biblical city of Shoushan), and a good number can trace their ancestry back to the city itself. While establishing an ancestral lineage to Queen Esther is not easy, the mere claim of this heritage is serious enough to have gained these “royal” Hamedanies a special place among their peers, sometimes even a favorable one.

My grandmother, of blessed memory, grew up in a city near Hamedan and prided herself on her special connection with this holiday. Her delicious cookies, called Koloocheh Purimi, were famous and sought after. Indisputably a prototype to hamantashen, these cookies were made by the women of each household and distributed to friends, family and neighbors in celebration of Purim.

My grandmother made three kinds of cookies, two with fillings and one plain. The plain were small circles, and those with a pasty mass of cooked dates were larger circles. Her third kind were dumpling-shaped and stuffed with hazelnut filling. As a child watching my grandmother knead the dough, I had the special privilege of making the Haman dummy (Haman is the antagonist in the Purim story). In contrast to my grandmother’s highly sophisticated work, my dummy was a rough figure made of plain dough that was baked with the other cookies, then thrown away. No one wanted to eat Haman anyway, so it was permissible to have the figure’s disposable existence defaced by my unskilled hands. There was halvah as well, served as a second offering. The memory of my grandmother’s beautifully decorated dishes filled with sumptuous sweet offerings invokes a magical blend of the aromas of rosewater, cardamom and saffron — the scent of Purim.

My grandmother took Purim very seriously. She fasted, went to the Megillah reading twice, and considered giving away her cookies her divine duty. She had developed a science of producing the perfect dough. She would wake in the middle of the night to cover the dough with the fastidiousness of a mother tending to her firstborn. Days in advance, she baked practice batches to pick out the perfect ingredients in perfect proportions. After she immigrated to Los Angeles, her nieces and nephews and their children would drive from miles away to take her on “cookie getaways.” These were weekends during which they would together make industrial numbers of cookies under my grandmother’s supervision. Koloocheh Purimi were her trademark. A generation or two ago, all Iranian-Jewish households had their own brands of Purim recipes — just ask them.

Today’s Iranian Jews celebrate Purim in the same way as everyone else. They purchase their casino-night tickets in advance, buy hamantashen baskets as offerings for their friends, and catch a few minutes of the Megillah reading if they happen to be at the synagogue for their kids. But why would a kosher Persian Jew suddenly become a goldfish lover around Purim? Who has ever seen a live fish costume at Purim masquerades anyway? Or, could there be a special goldfish dish for the feast that we do not know about?

It is no secret to the inhabitants of Beverly Hills that Iranian Jews are not ordinary Jews. About 40 years ago, when the wave of Jewish Iranians fleeing the Islamic revolution arrived in Beverly Hills, it brought with it Nowrouz, otherwise known as the Persian New Year. The majority of Jews in exile celebrate the Persian New Year, which, following the solar calendar, usually occurs a few days before or after Purim, celebrating the onset of spring. Although Nowrouz originates in Zoroastrianism, it is considered a secular holiday. To celebrate, Iranians set up a table called Haft-Seen with seven obligatory items whose names begin with “s.” The goldfish, whose name does not begin with an “s,” is exempt from this rule. It is there to represent the stars and their movements with its sparkling gold color and circular swimming pattern. Moments before our planet shifts into a new path around the sun, Iranians, along with Afghans, Tajiks, Uzbeks, Turks, Kurds and some other nationalities, gather around the table, filling their hearts with hopes and dreams for the New Year.

Remarkably, this holiday still thrives 900 years after the arrival of Islam in Iran. The new rulers may have managed to convert all but a negligible portion of Iranians to Islam, destroyed Zoroastrian literature in its entirety and changed the Persian alphabet to Arabic script, but Nowrouz survived. Along with the Persian language, Nowrouz defied this cultural annexation.

In the Iran of the 1970s when I was growing up, this holiday was all the rage. Spring cleaning began a month before, and people rushed to prepare for the festivities. At least 15 days before the end of the year, everyone grew Sabzeh, a plate of green-colored sprouts, to decorate their Haft-Seen table. Garlic (seer), apple (seeb), vinegar (serkeh), gold coins (sekeh), sweet pudding (samanou), dried oleaster (senjed) with additional items such as a mirror, a prayer book, a poetry book and, of course, the bowl of goldfish, would be laid out for a period of two weeks. The country would revel in festivities until Sizdah-beh-dar, when the entire nation would welcome the spring and the new year by picnicking and becoming one with nature.

Our family, like most other Jewish-Iranian families of this period, celebrated this holiday. Yet I could not help but notice my grandmother’s unusual awkwardness in setting the Haft-Seen table. Always in command when it came to Jewish holidays, she appeared lost with regard to Nowrouz. She would often ask her grandchildren to help with the preparations and setting the table. She would never make the essential sweet pudding herself, and she even sometimes passed the crucial moment of spring equinox absent from the table, tending to her Purim cookies.

One day, I asked her: “Grandma, how did you celebrate Nowrouz when you were young?” In response, she looked away, screwed up her face and bit her lower lip, searching for a way to dodge the answer. “Times were different when I was growing up” was all she managed to say.

It would take more than mere questions and answers to understand her reaction. Truth be told, celebrating

Nowrouz for Iranian Jews is a relatively new phenomenon. My grandmother, along with other Jews born at the beginning of the 20th century, never really celebrated Nowrouz while growing up. Subjected to periodic pogroms in addition to natural and manmade calamities, the Jews did not have an easy life. There are always exceptions, but the majority of Jews in Iran lived in such poverty that they were lucky if they could meet their needs and observe their Jewish holidays.

As recently as 90 years ago, Iranian Jews lived as disenfranchised subjects, and tending to their affairs was the task of the ministry of foreign affairs. Exorbitant extra taxes for being a Jew were officially enforced until 1881, a practice that endured unofficially for decades after its suspension. They were confined to ghettos, and their living conditions were lower than country’s average. Even if they wanted to, the Jews of Iran could not celebrate Nowrouz. It was a gentile’s holiday.

But stars shifted, and Jewish life in Iran changed for the better. During the reign of the Pahlavi dynasty, which started in the 1920s and ended with the revolution that began in 1978, Iranian Jews enjoyed equal status as citizens. For a short-lived historical moment, they thrived. They were able to leave behind their ghettos en masse and climb the ladder of social and economical success. They felt Persian more than ever and as loyal subjects, gave much back to their country.

My grandmother never confided in me, but I believe it was only after her children entered the university and socialized with other Iranians that she had started to celebrate Nowrouz. After all, her children’s friends would come to pay their respects for the New Year and taste her delicious cookies; and how could one not have a goldfish?

My Persian-Jewish home has been bustling with action. I have spent a good part of the past few days preparing. Casino-night tickets in the purse, kid’s costume in the closet and the goldfish is on the credenza. I still have so much to do, but I just had to try to make my grandmother’s cookies myself. This is her holiday, after all. I prepared the dough last night and have already made a batch. My cookies are nothing like Grandma’s, but they are better than what you buy at Ralphs, for sure. I place a new batch in the oven and set the timer. I use the time to organize my Haft-Seen table. I still need to drop by the Persian supermarket to pick up the senjed, but the green sprouts are looking good as I look at their reflection in the mirror. I check the timer to see how much time I have.

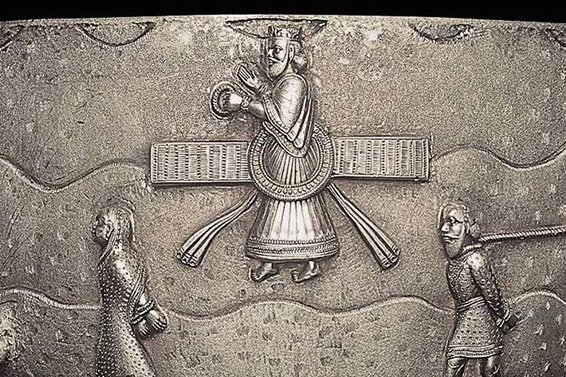

Good. I have enough time to select the clothes I want to give away. Purging closets is important when you do your spring cleaning, is it not? And think about how much ahead I will be when it is time for Passover cleaning! I pick out the traditional Persian outfit, which was sent to me 30 years ago. It doesn’t look that bad; if it still fits, I might wear it to the masquerade. I rush to put it on. There is even a headpiece that goes with it, and a pair of traditional clogs, too. I am looking around for a mirror when the goldfish catches my eye. I am mesmerized by its movements. Shining like a star, it moves around the fishbowl in circular motions. They say that at the moment of vernal equinox, the fish makes a sudden move and shifts its path of motion, just like our planet. Goldfish have been part of Nowrouz for thousands of years, even at the time of Queen Esther. I imagine her tending to her royal Haft-Seen as she prepares for the New Year. I imagine her staring at the goldfish while contemplating when might be a good time to ask the king for her people’s salvation. Who would turn down a favor on Nowrouz?

The timer rings. I look away from the goldfish and into the mirror. I see a Jewish woman in traditional Persian garb next to her goldfish. It all fits.

Published on Jewish Journal