Electronic Voting Machines, 500 officials for big, fat Parsi polls in Mumbai

With just a week to go for the Bombay Parsi Punchayet (BPP) elections, aspiring trustees have been giving stump speeches at colonies across Mumbai. On Wednesday, three candidates, who are canvassing together as “The Tremendous Three” were speaking at Colaba’s Cusrow Baug — a citadel of lemon yellow buildings, green lawns and vintage Fiats. With over 5,000 apartments and many commercial establishments under its control, the BPP is the city’s largest private landlord and Cusrow Baug is by far its most lucrative property with flats selling for upwards of Rs 5 crore.

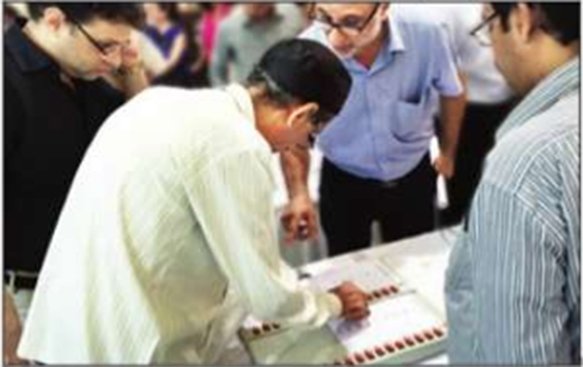

Given the wealth at its disposal, it’s no wonder that the BPP poll is being taken very seriously by Mumbai’s Parsi community, which numbers just 40,000. In the run-up to the October 18 polls, 250 election officers have been busy conducting mock drills, scouring the electoral rolls for duplications, arranging for ambulances at the five polling stations and pressing candidates to stick to a voluntary code of conduct. Community papers and magazines — one of which is owned by a candidate — are rife with testimonials, voting FAQs and full-page ads that can cost up to Rs 55,000, and even aspirants are interrupting their chest-thumping rhetoric to give live demonstrations of the newly-introduced Electronic Voting Machines (EVM).

Given the wealth at its disposal, it’s no wonder that the BPP poll is being taken very seriously by Mumbai’s Parsi community, which numbers just 40,000. In the run-up to the October 18 polls, 250 election officers have been busy conducting mock drills, scouring the electoral rolls for duplications, arranging for ambulances at the five polling stations and pressing candidates to stick to a voluntary code of conduct. Community papers and magazines — one of which is owned by a candidate — are rife with testimonials, voting FAQs and full-page ads that can cost up to Rs 55,000, and even aspirants are interrupting their chest-thumping rhetoric to give live demonstrations of the newly-introduced Electronic Voting Machines (EVM).

At Cusrow Baug, one contender pulled out a dummy machine and began explaining the nitty-gritties of the process. “Each booth has two EVMs because a single machine has only 16 slots and there are 23 candidates,” he told the crowd of over a hundred senior citizens, some of whom had expressed fears of “rigging”.

“It’s not a touch screen so ‘dabao’ the button for the red light to come on,” he added. Since five out of seven seats are up for grabs, voters can select up to five candidates. An exhaustive set of EVM FAQs, created by the BPP’s election team, deals with every question imaginable from “Can I undo my selection?” to “What if there is a power failure?” to “Can I vote for the same candidate multiple times?”

Last year, India conducted the world’s largest election when 81.4 crore people – larger than the population of Europe – cast their vote in 9.3 lakh polling stations fitted with 14 lakh EVMs. This election might be diminutive in comparison – a maximum of 15,000 Parsis are expected to cast their vote at five centres fitted with 100 EVMs – but it’s being arranged with the same earnestness. “At each centre, there will be an in-charge polling officer and three to four assistant polling officers, who are established members of the community” he says. “The whole mobilization will be nearly 500 people, of which 230 will be polling agents from the candidates’ side, and a hundred IT support staff for the EVM machines.” One booth in each centre will be reserved for handicapped voters, wheelchairs will be available at all polling centres and three ambulances will be on standby for elderly voters.

The entire process, which includes hiring EVMs and an external IT audit firm to oversee the polls, will cost the BPP Rs 25 lakh, says Dastoor. And will have to be repeated in six months’ time when one of the two currently-occupied seats is vacated. On Election Day, people will have to show their election cards and a government-sanctioned ID, their name will be ticked off an online electoral roll and their forefinger will be marked with indelible ink. A dry run of 150 voters has already been conducted in Khareghat Colony to evaluate how long each voter will take to complete the process and ensure that there are no hiccups. The results will be declared the same evening at the Dadar Parsi Colony Gymkhana. One curious lacuna in this otherwise water-tight process is that when voters register to be added to the electoral roll, there is no way of verifying that they are Parsi. “Your passport, your Aadhar card, nothing mentions your religion,” says Dastoor. “It’s only based on the name.”

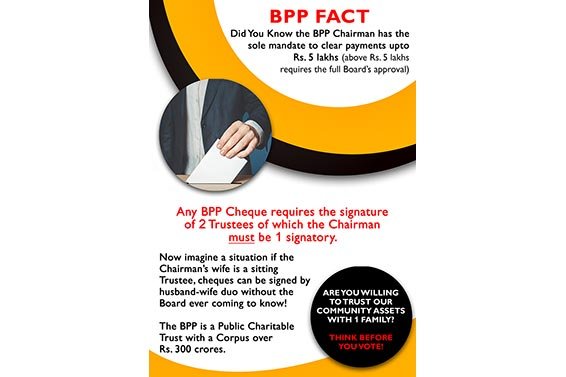

Many view this as a make or break election because the current board’s rival factions have spent the majority of their terms blocking each other’s proposals and hurling allegations – and abuse – at each other. According to the editor of the Parsi Times Freyan Bhathena, “The fate of this community depends on these elections.”

Which is perhaps why for the first time in over a 100 years, the BPP has also created a voluntary code of conduct. It asks candidates to refrain from luring voters with expensive freebies like cell phones, laptops, flat screen TV sets, and refrigerators. In the past, some candidates even organized buffets and retro nights in Parsi baugs, while others wined and dined voters at swanky restaurants. It’s these extravagances, which led the code’s formulators to impose a cap of Rs 3 lakh on campaign expenditure. Additionally, to avoid the mud-slinging that has shadowed past campaigns, the code also asks candidates to “restrict criticism to polices, programmes, past record and work only”. “The code of conduct has definitely made a difference. It is far more gentlemanly, far more orderly,” says Jehangir Patel, who runs the community magazine Parsiana. Bhathena agrees though she credits the Parsi press for educating voters more than the newly-introduced code of conduct.

Community member Farrokh Jijina, however, says personal attacks continue but have simply switched mediums. “It’s there but it is surreptitious. Now, personal allegations are coming on Whatsapp and other social media.”

Published on Times of India