Thoughts while SPARSEE-ING: Three-part photo book tells story of three Parsi families from a unique perspective

So, what is exactly is ‘sparseeing’? To borrow one of Atticus Finch’s quotable quotes from To Kill a Mockingbird, it is just like ‘stepping into another’s skin, and walking around in it for a while’

I was witness to one of the last remaining members of the dying Parsi community of Jamshedpur entrusting two friends with a wooden box of what we would later find out could be termed as his most prized possessions.

It was either a restoration of all we had in hand, or we could see before our very eyes the vanishing of poignant memories that proved a family’s existence, origin and most importantly their contribution to the making of the industrial township of Tatanagar, India.

Flashes of the cover of Robin Sharma’s eye-roll of a book “Who will cry, when you die” swept past my eyes as I looked into eyes of those in portraits spanning generations of Parsis, asking me the question: “Remember me, will you?”

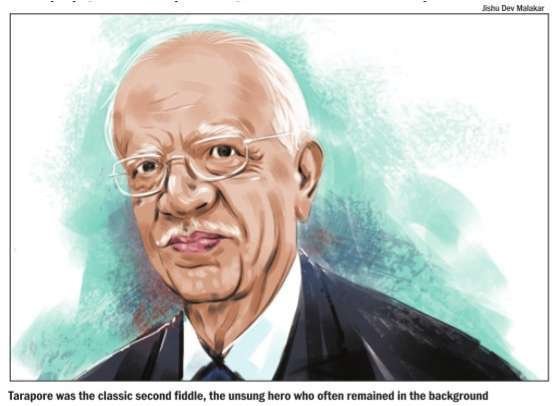

Khurshed M Barucha was the first Indian cashier of Tata Steel. He was married to the daughter of Homi C Engineer, another very old family of the region with their home in Maāngo district.

Members from the Engineer family had served in the Afghan War, and some even had mothers originally belonging to Karachi! Post-marriage to Goolbai Engineer, grand old man Bharucha took a loan of rupees 3.5 lakh from “a friend who owned an island (!) near then Bombay”, say the grandsons today, and I quote verbatim: “It is with that money that Bharucha built the mansion which used to house the single screen-theatre, Regal Cinemas, below.

“From our grandfathers and old newspaper cuttings that they’d saved up, we’d heard that around 3,000 Parsi families from places like Surat and Bombay and Karachi and sometimes even Birmingham and Munich, had relocated here after the setting up Tata Steel in 1907. Only 200 families remain after years of exodus, interfaith marriages and subsequent dwindling down.”

How does one stare the brink of extinction right in the eye without flinching? The least you can do is to hand over the agency to tell their story like they’d have it told.

The photobook whose making I was fortunate enough to be a part of, is called SPARSEE-ing and it’s currently still in construction by an independently-run publishing unit we run called Provoke Studios. And that is exactly why it’s still so fresh in my memory.

So much so, that when I saw the occasion of the Parsi New Year approaching this month, I could not help but pen down this little something to give context to why we chose to take up this huge initiative, our situatedness in the town of Tatanagar, and why we ultimately resort to fiction in this three-part photo book collection called Sparsee-ing.

Once you open the photo box, you find yourself being pulled into a universe comprising a playful array of different forms like postcards the Gazdars used to receive from concerned aunts and uncles in Birmingham or from grandfathers working in the locomotives division of Tata writing from cruises while ensuring the mechanical plants and engines assigned to their scrutiny for regular maintenance were in working order.

Entitled “Younger Days”, this section attempts to build a fictional tale around the whereabouts of the aforementioned Mr Barucha.

Based on the snippets of information we gather from his grandson, we felt that it was essential to wrought out a character sketch of him, along with the Parsi aesthetic of the time he embodied.

Sometimes fiction is closest one can get to the truth.

Apart from postcards, reiterating the truism that Parsis used to travel a lot, owing to their close links to industries such as shipping and steel and yes, the army, there is another quirky element entitled “The Sad Little Shoebox” which makes for the second part this photobox/universe.

The series of images comprise an accordion made up of single-screen theatre advertisements hand-printed onto glass slides the size of a floppy disk for projecting in the single-screen Parsi cinema hall called Regal Cinemas, which used to be run right below what now stands as the dilapidated Bharucha Mansion at the Bistupur junction of Tatanagar.

They were literally handed over to us in ‘a sad little shoebox’ filled with cobwebs. A media is best representative of its time. These glass slides with hand-painted Murphy Radio and Gold Spot beverage ads point to how the Parsis dipped their fingers into the cultural milieu of the time.

The third section of Sparseeing called “Your Studio Crumbled and Died”, is a book of portraiture, most taken with large-format studio cameras of the time, and some even being preserved as cabinet cards and albumen prints. We were transported into a world of checkered marble floors, jet black Morris cars, the wavy hairstyles of Parsi women, the occasional string of pearls around a neck, the blouses revamped to match European frills and puffs with oriental Parsi embroidery on lace and silk with Iranian motifs.

So, what is exactly is “sparseeing”? To borrow one of Atticus Finch’s quotable quotes from To Kill a Mockingbird, it is just like “stepping into another’s skin, and walking around in it for a while”.

Instead of criticising portrait photography of yesteryear for problematic representations and ethical concerns related to the “gaze” and the “outsider”, sparseeing urges us to, just for a few minutes, try and change perspective and see from the inevitably greener side of the fence.

But the question you find yourself asking at the end of it all is how green exactly is the grass below their feet today?

Almost all the images of photo box collection Sparseeing reek of a desire to leave something behind, to partake in the creation of history itself. Putting the three sections together enables this, albeit with a bit of romanticising.

Source: https://www.firstpost.com/india/thoughts-while-sparsee-ing-three-part-photo-book-tells-story-of-three-parsi-families-from-a-unique-perspective-9894571.html