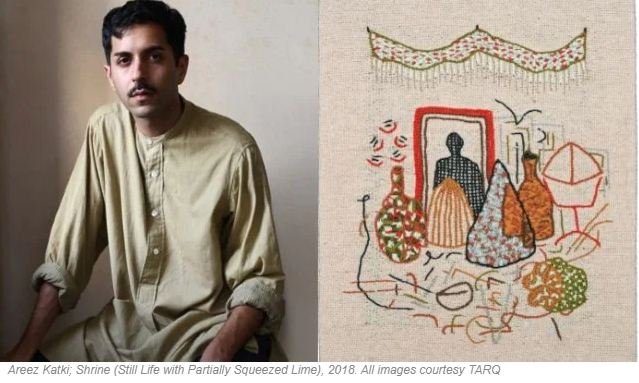

Areez Katki on first solo show, and using art to explore notions of home, identity

As an 8-year-old child, artist Areez Katki started to process art as a visual and experiential medium, through attentively observing the way the women of his family participated in textile weaving, embroidery, hand knitting, and more. The arts generally deemed as belonging to the domestic, or women’s sphere, were deemed as lower art. Growing up in New Zealand, in school he was then exposed to American and European frameworks of art, understanding it from the Western, post-colonial dynamic, which then led on to a Bachelors of Arts in Art History at the University of Auckland. Combining the two has allowed him to develop his unique visual language that challenge the Western, heterosexual, and patriarchal conceptions of art. “The effect has been really wonderful and one that challenges the hierarchies of high art and low art and also of East and West,” he tells Firstpost.

Katki returned to Mumbai in 2018, his first visit as an adult, to a house where he’d spent his first night as a child and where “four generations from my mother’s side of the family had grown up and lived.” Now, having the house entirely to himself greatly influenced Katki, giving him clues into what the space of domesticity, of interiority, looked like. It was a space removed from the “glamorous, extravagant, wealthy, extroverted Parsi world”, one of silence, introspection, and family archives. “The house was a great source of intelligence for me,” says the artist. “I started finding ways to talk to the house.” This included cleaning surfaces, renovating broken china or boxes lying about, opening and clearing out drawers, discovering his mother’s old diaries, and learning more about his family.

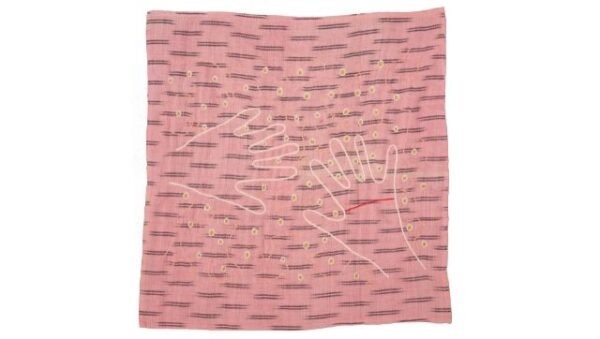

Hands on lap, 2019

Cotton thread hand embroidery over Ikat

handkerchief

18.5 x 18.5 inches

Copyright: Copyright Areez Katki, 2019

Courtesy: Courtesy of Areez Katki and TARQ

Especially important were the textiles he found around the house. The katkas, dust cloths, tea towels, napkins, Bombay Dyeing linens, and other such cloths have made their way into Katki’s first solo exhibition in India, Bildungsroman (& Other Stories), at Mumbai’s TARQ art gallery. In using the cloths from around the house, he’s relinquishing the flashiness and resplendence of the Parsi garas, jhablas, and kors. In his choice of cloth, he has stripped bare the heavy embroidery and gold jewellery, and focused on the simplicity of something bare and relatable.

“I liked the idea of democratising my heritage by introducing a layer that was interior, humble, spoke about the surfaces of childhood memories, and was something intimate, and not about showiness or being wealthy.”

Cotton thread hand embroidery on 60% silk/ 40%

cotton khadi textile. Mounted with NZ pine dowels.

51.3 x 22 inches each

(diptych)

Copyright: Copyright Areez Katki, 2018

Courtesy: Courtesy of Areez Katki and TARQ

These cloths, besides being a family archive, are also symbols of togetherness and familiarity within the Parsi community, appealing to the two strands that lent themselves to the exhibit’s name. It borrows from the literary concept of describing a protagonist’s formative years, including psychological and moral development. “For me that transformation comes from, on the one hand, [being] an outsider entering into the Parsi world, observing the aftereffects of colonisation from within Parsi walls, criticising it, and also observing it from a distance. The other part is the person who comes home to claim his place because for migrants a home is many things.” Working on Bildungsroman has also affected his idea of home. In one sense, this was home. The Tata Parsi Colony, Tardeo, and South Bombay in particular is another type of home. “Zorastrians haven’t had land of their own since the 8th century AD, therefore India is a type of home for a Parsi.” In yet another sense, home is where he centres his work, and where his loved ones live. “For me home is a very plural term.”

Areez Katki talks us through two of his works from Bildungsroman (& Other Stories):

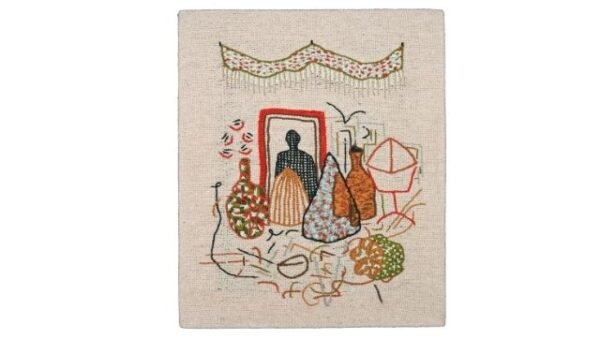

Shrine (Still Life with Partially Squeezed Lime)

Shrine (Still Life with Partially Squeezed Lime), 2018

Cotton thread hand embroidery on cotton khatka

14.9 x 12.5 inches

Copyright: Copyright Areez Katki, 2018

Courtesy: Courtesy of Areez Katki and TARQ

“Shrine (Still Life with Partially Squeezed Lime) looks at the tradition of interiority when one prays. The Parsi shrine is quite a compact one filled with little objects that are offerings. And one main recurring feature in all Parsi shrines is the use of a mirror. And Shrine (Still Life with Partially Squeezed Lime) is a quotidian scene that looks at the shrine from my [neighbour] Aunty Dolly’s house. The shrine is taken from one of Dolly’s little shrines around her house. The red frame containing an anthropomorphic or vaguely human spectre is a recurring motif in my work, where there’s a shape of a man but no detail because of migration and the result of being a person who has a complicated relationship with stillness and home.”

*

Massacre of the Tall Poppies

Massacre of the Tall Poppies, 2018

Cotton thread hand embroidery on cotton mul

sudreh

26.9 x 25.9 inches [variable]

Copyright: Copyright Areez Katki, 2018

Courtesy: Courtesy of Areez Katki and TARQ

“Massacre of the Tall Poppies has two layers. The poppies are stylised in a vegetal motif on a sudreh, all being cut down by scissors or farming [equipment] or axes. [This represents] tall poppy syndrome, when a person within a certain social framework starts rising above the rest and starts feeling self-conscious because of their heightened status, and therefore starts shrinking or is cut down by the rest of society because of their alleged audacity for standing out.

The second layer is a humorous link but also a very critiquing, dark link to the early traces of how Parsis went on to procure wealth during a colonial British Raj. Opium trading was a very popular way in which a lot of these Parsi families acquired their fortunes and therefore I felt inclined to mention at least the iconography of the poppy which is a very beautiful flower but also a flower that has dark connotations. So you’ll see a lot of opium poppy pods as well as those red poppies sort of scattered across the sudreh in a blood red colour.”

***

Source: Click Here