A film brings the trajectory of Bombay’s Parsis to life

The story of Kekee Manzil — The House of Art is the story of Mumbai’s Parsis, looked at through the life of one iconic person.

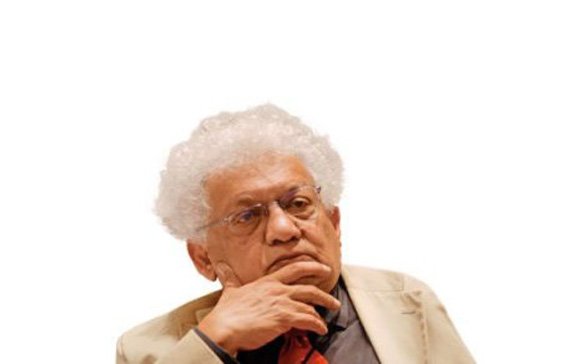

The documentary film takes us through the life of the late Kekoo Gandhy (1920–2012), the famous art gallerist and picture frame manufacturer who was the owner of the popular Chemould Frames shop at Mumbai’s Kala Ghoda neighbourhood. But the film is also a nostalgic visual journey of Bombay in the 1980s and 1990s, which charts the history of the Parsi community in parallel.

The filmmaker Behroz Gandhy, Kekoo’s daughter, has sketched his life through her own narrative voice as well as through family videos, photos, and memories.

Told through the eyes of father Gandhy, whose family was one of the first members of the Mumbai modern art movement’s inner circle, the film offers a first-hand sneak peek into the lives of some stalwart international artistes who broke into the canon of modern art trends back in the day — from MF Husain and Salman Rushdie to Anish Kapoor, through archives as well as exclusive interviews.

Reflection of the community

The Parsi aesthetic — like a dilapidated old bungalow that stands solid and is lit by nothing other than a faded kind of sunlight — is the essence of this documentary’s memory of that older Bombay, one that today is found only in colonial era photographs of the city. These images depict a certain dying Anglo Indian culture, which is similar to that of many Parsi households.

The film uses natural light beautifully to showcase the barren wooden interiors of the Kekee Manzil house and the rather vacant streets and beaches of the city that stand as a testament to the psychocultural plight of a vanishing community.

After all, had this film been made by someone else or about someone else, one would have seen a very different kind of Bombay from the one this shows.

In a webinar held on August 17, researcher and curator Anish Gawande also saw a strong reflection of Bombay in the film. “The film is about a city that’s changing, a city that’s shifting […] in the post-Independence era,” he said. “You are also seeing an expansion of the city into new avenues, into spaces outside Bandra, into spaces outside the traditional islands,” he added.

Nostalgia is explored in the documentary also through a strategic use of old Bollywood songs for background music. At the heart of this isolated nostalgia about the city is a psychological experience that is hard to miss.

The film makes a passing remark about Kekoo Gandhy being diagnosed with bipolar disorder, which left me wondering how this experience of community isolation of the Parsis is linked to mental health in the shifting urban landscape of a city like Mumbai.

The ‘neutral’ Parsis

Kekee Manzil follows the trajectory of several themes explored in post-Partition and post-riot Indian fiction, such as Bapsi Sidhwa’s novel Ice Candy Man and its adaptation in the Hindi film 1947: Earth or even the 2005 film Parzania. They have all attempted a resurrection of the Parsi identity, one that is caught between Hindu-Muslim violence and stands resolutely ‘neutral’.

This Bombay, one that was torn by riots and communal tensions, becomes a metaphor for certain communal identity politics that Kekoo tried to fight against. Especially since the city he inhabited was being increasingly torn on religious lines, which Gawande observes, “and you’re also seeing a certain ghettoisation and a certain division into pockets that require space to re-imagine what Bombay lives for, what Bombay stands for.” In that context, Kekee Manzil will be remembered as a refuge.

“Amidst all this, Kekee Manzil emerges as a space for several of these faiths, and several of these communities and ideologies to come together. But it also becomes a hiding space for those who are threatened by the state. It also becomes a space to think about the future of the city,” he says.