The veiled history of India’s first woman lawyer

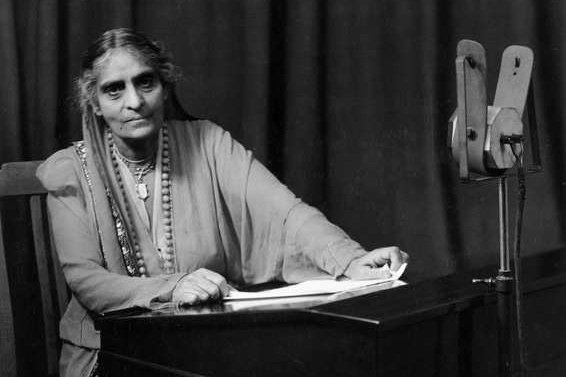

Madame Cama is not the only right answer to the trivia question: “Name an Indian social reformer who wore her saris the other way around”. Cornelia Sorabji, India’s first woman lawyer, was an equally arresting figure of colonial India, a well-spoken, complicated personality who sheathed herself in brilliant silk Parsi-style saris paired with elaborate Victorian blouses and long, dangling necklaces as something of a deliberate cultural marker.

July 6 marked the 65th death anniversary of Sorabji who died in London in 1954 and whose legacy is marked by a glaring irony: Though this pioneering barrister fought chiefly for the rights of veiled women, her own contribution remains obscured in history by a thick metaphorical purdah woven from her controversial ideology and identity.

July 6 marked the 65th death anniversary of Sorabji who died in London in 1954 and whose legacy is marked by a glaring irony: Though this pioneering barrister fought chiefly for the rights of veiled women, her own contribution remains obscured in history by a thick metaphorical purdah woven from her controversial ideology and identity.

Without Sorabji, an Indian civil servant whose heart used to beat with two pulses–“one for India, one for England”, the Raj era chapters of this nation are poorer for various reasons. Born in 1866 in Nasik–which was a part of the Bombay Presidency then–she came with complex roots. Her father Reverend Sorabji Kharshedji, though of Zoroastrian lineage, had converted to Christianity in his teens, and her mother, Franscina, a Hindu from the Toda tribe in Tamil Nadu, was adopted and raised Christian by an aristocratic English army officer and his wife. “There was an invisible circle drawn around [our family] … which made it untypical of the Indian home of the period,” Sorabji once commented about the household that not only infected her with respect for the best of both Indian and British traditions but also baked a zeal for social service into her bones.

In her memoir ‘India Calling’, Sorabji recounts the case of a hapless “Guzerathi Hindu” widow who had been cheated of her property by her manager and had come to Sorabji’s mother for recourse. Rankled by the servitude experienced by women who led a secluded life behind the veil or ‘purdanashins’, she resolved at an early age to fight legal battles for such wives and widows, a path that saw the well-read Sorabji accumulate a litany of firsts: the first woman student of Pune’s Deccan College (where boys apparently slammed lecture hall doors in her face to prevent her from attending lectures), the first female graduate in Western India and, most dazzlingly, the first woman to study law at England’s University of Oxford.

Predictably, before she could champion women’s rights, Sorabji had her own share of gender battles to fight. For one, despite securing a top rank in BA at Bombay University, she was denied a Government of India scholarship for pursuing higher studies in England on grounds of her gender. Then, when she enlisted the financial help of a number of English well-wishers and sailed for England in 1889, she would not be admitted to the Oxford degree despite passing the bachelor in civil law exam in 1892. Women gained the right to study law in Oxford only in 1919. So, even though Sorabji was technically the first woman to study law in England, she could not enroll in the Bar until 1923, a year after an English student named Ivy Williams became the first woman to claim that honour.

Given that women did not have the right to plead before courts of law in India, a defiant Sorabji–who was doing educational work in Baroda–even appeared for an LLB exam in Bombay University and a pleaders’ exam in Allahabad on her return. However, despite passing, she would be refused registration as a practising lawyer on grounds that she could not “cite the precedent of a woman vakil”. Yet she persisted. Not only did she persuade the bureaucracy to appoint her the lady legal adviser to the court of wards in Bengal, Bihar, Orissa and Assam for women in purdah whose estates were administered by the courts but also contributed to the infant welfare and nursing programmes, which saw her becoming associated with the Bengal branch of National Council for Women in India.

Many purdahnashins would often express surprise at her position as a “Lady Commissioner” and Sorabji’s stint at a solicitor’s office in Bombay even saw her fabricating a “kidnapping” once, rescuing a princess from a fort another time and, in a farcical case, representing an elephant who had filed a case against a Maharajah to protest the taking away of his banana grove. Sorabji “showed up in court in a carriage with six white horses, which had been sent for her and realised that the Maharajah was also the judge. He sat on a swing with a gramophone playing English songs and immediately pronounced the judgement in her favour since his English bulldog at the gate had liked her,” states an online magazine article on Sorabji.

Troubled by the excessive reformist zeal of Indian nationalists, the “Progressives”, who she felt, violated the beliefs and traditions of the orthodox Hindu majority, Sorabji even disapproved of Mahatma Gandhi’s strategy of mass mobilisation. She also caused a stir when she favourably reviewed Katherine Mayo‘s Mother India, a controversial book on India’s social and political life that Mahatma Gandhi famously called “a drain inspector’s report.”

If these contradictions–remaining loyal to the empire as an Indian civil servant and being fiercely anti-suffragist despite championing women’s reform–exiled her from Indian history, within the Parsi community, too, there has been limited acknowledgment of her because “she was not a Zoroastrian and because her mother was not Parsi (leave alone the fact that her Parsi father converted to Christianity),” says Patel about Sorabji who not only saw her identity but also life itself as woven cloth, not unlike the rich silk saris that set her apart everywhere she went.