‘Bobby’ Talyarkhan: The Pioneer Of Indian Cricket Commentary

Talyarkhan, Indian cricket’s first commentator, began speaking from a little corner of a Bombay maidan.

Talyarkhan, Indian cricket’s first commentator, began speaking from a little corner of a Bombay maidan.

In the ‘Signpost’ section of the magazine India Today, dated 15 August 1990, an announcement was made:

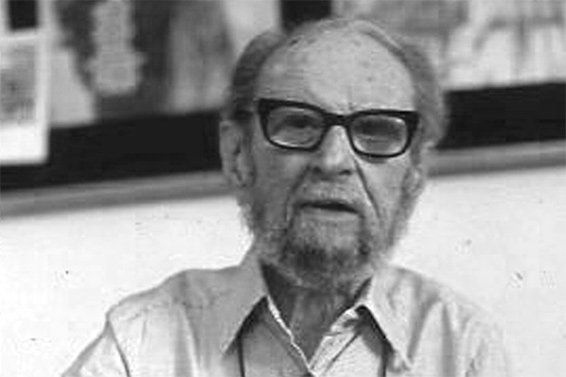

Died: Ardheshir Furdonji Sohrabji Talyarkhan, 93. A prolific and trenchant columnist even at his age, ‘Bobby’ Talyarkhan was a legendary figure in sports journalism. He was the first man to bring sports to the doorsteps of millions through his lively commentary on AIR.

To the few who remembered, it was indeed the end of an era. AFS ‘Bobby’ Talyarkhan (1897 – 1990) was Indian cricket’s first radio commentator.

Radio commentary had begun in the early Twenties, surprisingly not in England, the Home of Cricket, but in Australia. This took place in 1922 in a Testimonial match for Charles Bannerman (Test cricket’s first centurion) at the Sydney Cricket Ground. The first commentator was a gentleman named Lionel Watt. Five years later, the BBC introduced sports commentary in 1927 when the commentary of an England versus Wales rugby match was broadcast. The same year, the first cricket commentary was broadcast on BBC in the Essex versus New Zealand match at Leyton.

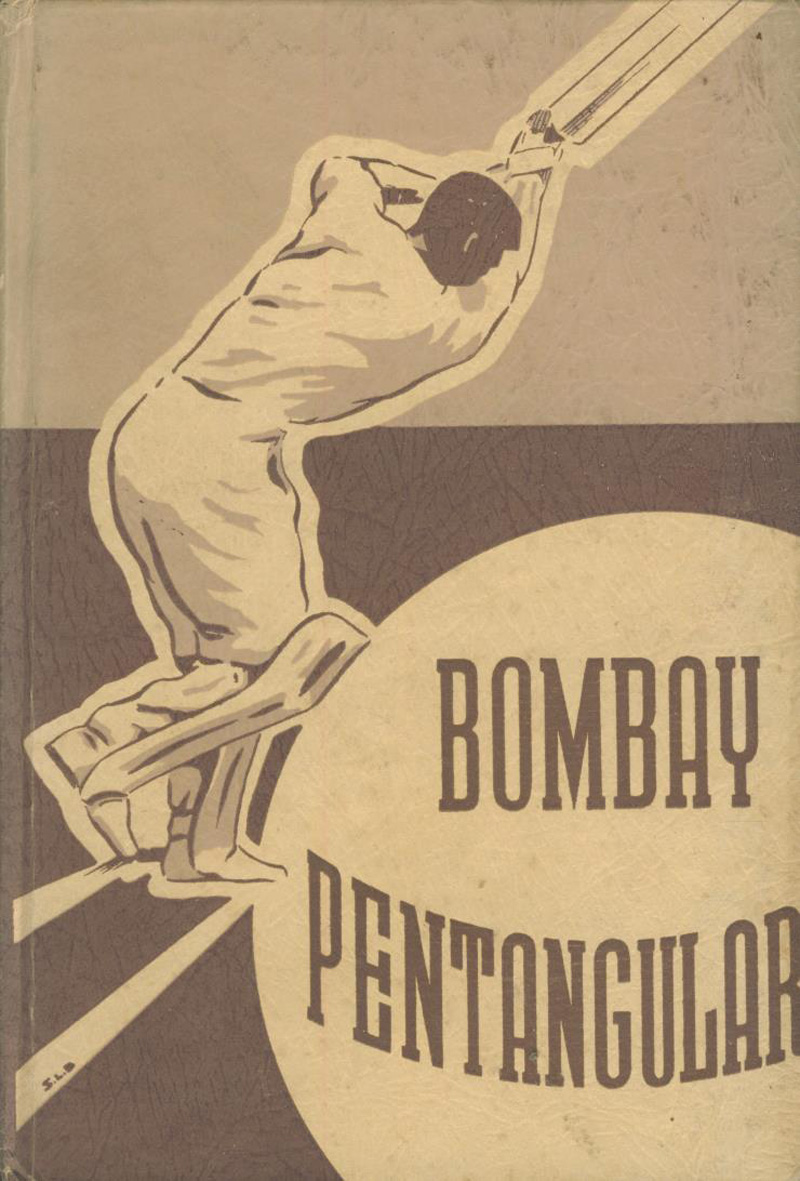

Talyarkhan’s tryst with the microphone began in 1934, when he commentated for the first time in the Quadrangular, in a match where the Parsis played the Muslims at the Esplanade Maidan. The Quadrangular, in its earlier version as the Triangular–and, in its later version as the Pentangular–was India’s premier cricketing tournament for close to four decades. It had its origins as the Triangular in 1907 with the Hindus, Europeans, and Parsis playing each other (before that, the Europeans and the Parsis played each other regularly).

From 1912 onwards, it became the Quadrangular, with the Muslims taking up the fourth slot. Much awaited and fiercely contested year after year, it was akin to the IPL of its time with many-a-youngster coming to notice in its annual contests and then going on to achieve everlasting fame.

From 1937, with the addition of ‘The Rest,’ consisting of Buddhists, Jews, Indian Christians, Anglo-Indians and on occasion, players from Ceylon (who on one occasion even included a Hindu) it became the Pentangular till the political climate in the country forced the cancellation of the tournament with its communal overtones in January 1946.

For the next decade and a half, Talyarkhan proceeded to broadcast ball by ball commentaries of the Bombay Quadrangular/Pentangular and the Ranji Trophy. When Bobby took up the broadcast, he did it alone. Ball after ball for six hours a day without a break (except for lunch and tea) prompting the renowned journalist and editor, Frank Moraes to comment: ‘Bobby’s bladder is as strong as his blubber.’

In A History of Indian Cricket, Mihir Bose mentions, in particular, Talyarkhan’s monumental feat of endurance at the 1944-45 Ranji Trophy final between Bombay and Holkar played at Brabourne Stadium in Bombay. Bombay, batting first, scored 462. Holkar made 360 in their reply.

In the second innings, Bombay buttressed by Vijay Merchant’s 278 and Russi Modi’s 151 amassed 764 leaving Holkar 867 to win. Holkar lost by 377 runs. The match, played over six days, had produced 2078 runs; almost 695 overs had been bowled–a grand total of thirty-three hours of play, all broadcast on air by Talyarkhan singlehandedly.

Besides being a broadcaster, Talyarkhan was also a sports journalist who was instrumental in gently persuading newspapers of the time to include a page that covered sport. And he was among the first to back Gandhi when he spoke against the communal nature of the Pentangular tournament in December 1940.

Even before Gandhi’s call, as Ramachandra Guha writes in A Corner of a Foreign Field, Talyarkhan had spoken up for the Ranji Trophy, which had begun in 1934 but had not yet caught the imagination of cricket spectators who still preferred the Pentangular. But by 1940, the Pentangular had become increasingly mired in communal mindedness, and, as Talyarkhan observed in an article entitled ‘The Future of Indian Cricket,’ communities were ‘afraid of losing, as if defeat meant the loss of cultural and religious worth!’

Five more years were to pass before the Pentangular would be finally done away with. Eventually, the Ranji Trophy would establish itself as India’s premier cricketing tournament.

Besides cricket, Talyarkhan was also a horse-racing aficionado. There is a horse-racing trophy named after him at the Mumbai racecourse, and he was also chief auctioneer when young foals would be auctioned.

And then after a decade and a half of commentary and thousands of enthralled listeners, came the axe. In 1949, All India Radio insisted on a commentary team, but Talyarkhan wasn’t willing to entertain such a notion. He left in a huff, never to commentate again.

He continued to write his columns though—‘Do you get me, Steve?’ (which was a reference to a favourite expression of his on air) and ‘Take it from me.’ In the early Seventies, he returned to radio for a short stint, on Radio Ceylon, doing a brief capsule on sporting events. In an apparent reference to Talyarkhan, Salman Rushdie, in his novel, The Moor’s Last Sigh, mentions ‘AFST’ and his ‘acerbic wit.’

So how was Talyarkhan as a commentator? Everyone, well, almost everyone, who heard Talyarkhan speak, recall his command over the language and his ability to bring the game alive. Then there was, as KN Prabhu, the noted cricket writer, put it, the ‘rich, fruity voice and a fund of anecdotes.’ One reviewer called his broadcasts, ‘firm, full of life, filled with the scent of playing fields.’ Only Mukul Kesavan, the historian and cricket writer, seems to have a contrary opinion; he calls Talyarkhan a ‘windbag.’ But, he also confesses to having never heard him and was basing his opinion on his columns in the Blitz.

Incidentally, Pakistani radio’s first commentating duos was Omar Kureishi and Jamsheed Marker, of whom, Marker, like Talyarkhan, was a Parsi, albeit from Karachi–not Mumbai. Commentary for cricketing events today has become de rigueur and is also a glamorous affair with many commentators as famous as the cricketers they cover.

The story began eight-odd decades ago, with the lone figure of Talyarkhan, speaking into the microphone in a little corner of a Bombay maidan.