Remembering Homai Vyarawalla, India’s first female photo journalist

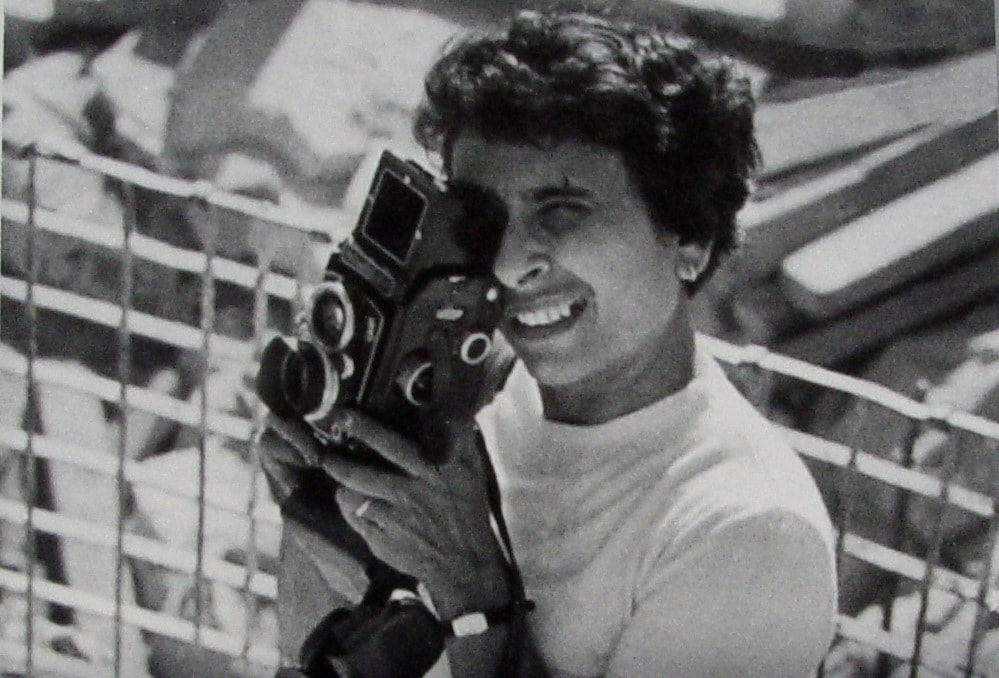

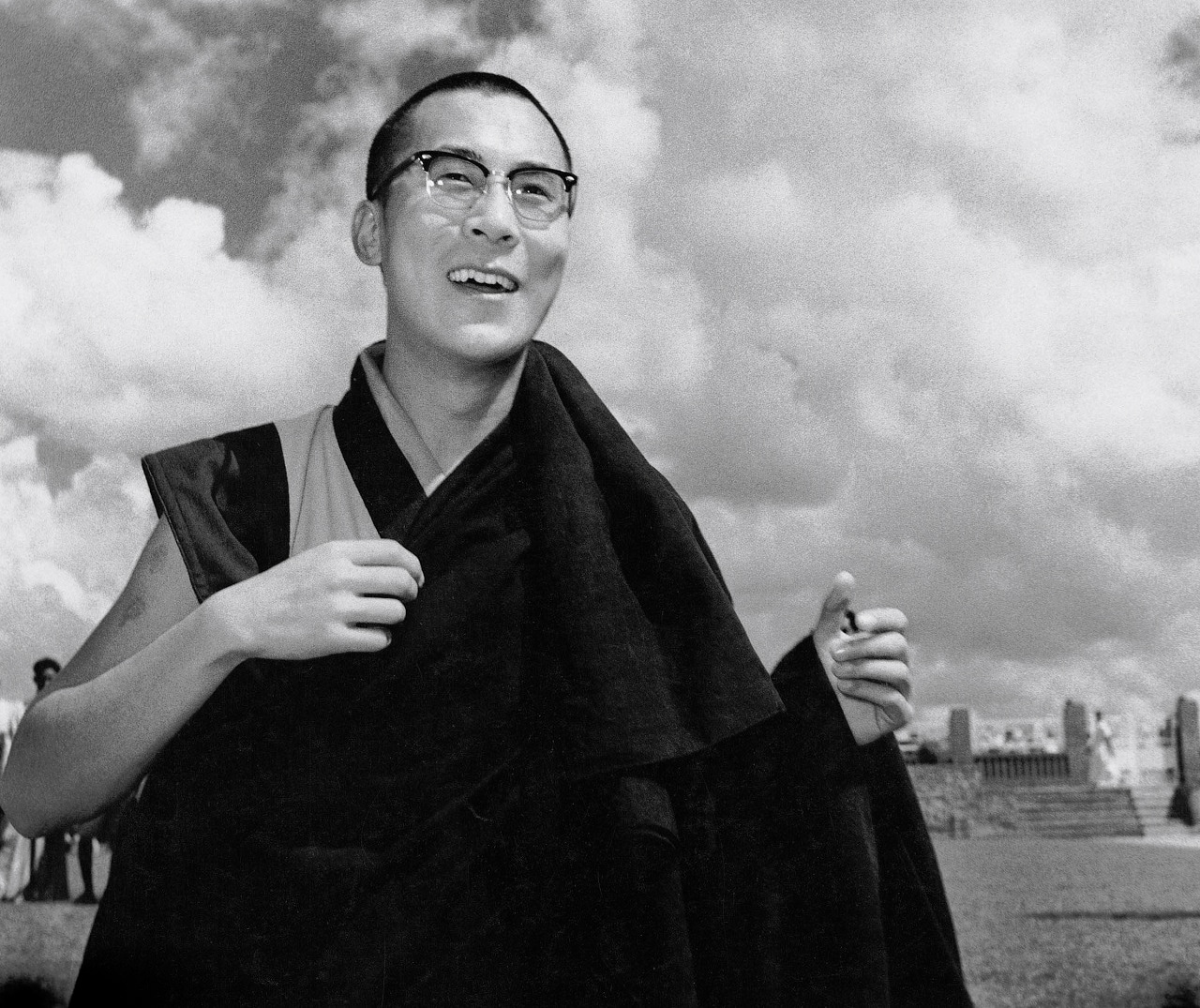

The year: 1959. In the crowd milling around the then young Dalai Lama who had just arrived in Sikkim, was a young woman with chiselled nose, deep-set eyes, a mop of mischievous curls, a heavy camera with wooden exterior and a flash that weighed nearly 9 kg.That was not all. She had two other cameras and even a hard-to-pin-down dupatta to deal with.

She was the only woman in the press corps that was flown in specially from Delhi to click the momentous occasion.On a Time-Life magazine assignment, Homai Vyarawalla, India’s first woman photojournalist, had to jostle with the multitude to get a good frame. She got the Dalai Lama smile and wriggled out of the melee.For 35 years, that was just one of the many moments that Vyarawalla shot for posterity as she criss-crossed the country shooting dignitaries, mundane moments, pompous princes and historic events. Often on a bicycle, wearing a khadi saree and carrying the equipment on her frail shoulders.

Had she lived, she would have been 106 today. Vyarawalla died in 2012, but her photographs — and stories of her grit — live on. I had met her when she was 93. Frail, age having furrowed her flawless skin, reduced her facility to hear a whisper, obliterated chronology from her calendar and blurred some faces but she could still take me to the beginning.

To Navsari, a sleepy town in Gujarat, where she was born to an actor from the Urdu-Parsi theatre and his homemaker wife. The family was seeped in indigence and the girl was packed off to Bombay to study where later came along a boyfriend and a passion, both to last a lifetime. The boyfriend — Maneckshaw Jamshedji Vyarawalla — professed love, she said yes and the two married 15 years later. Much happened in between. Vyarawalla acquired a honours degree from Bombay University and a diploma in art from JJ School of Art, and between classes she was tinkering with the camera under the guidance of Maneckshaw.

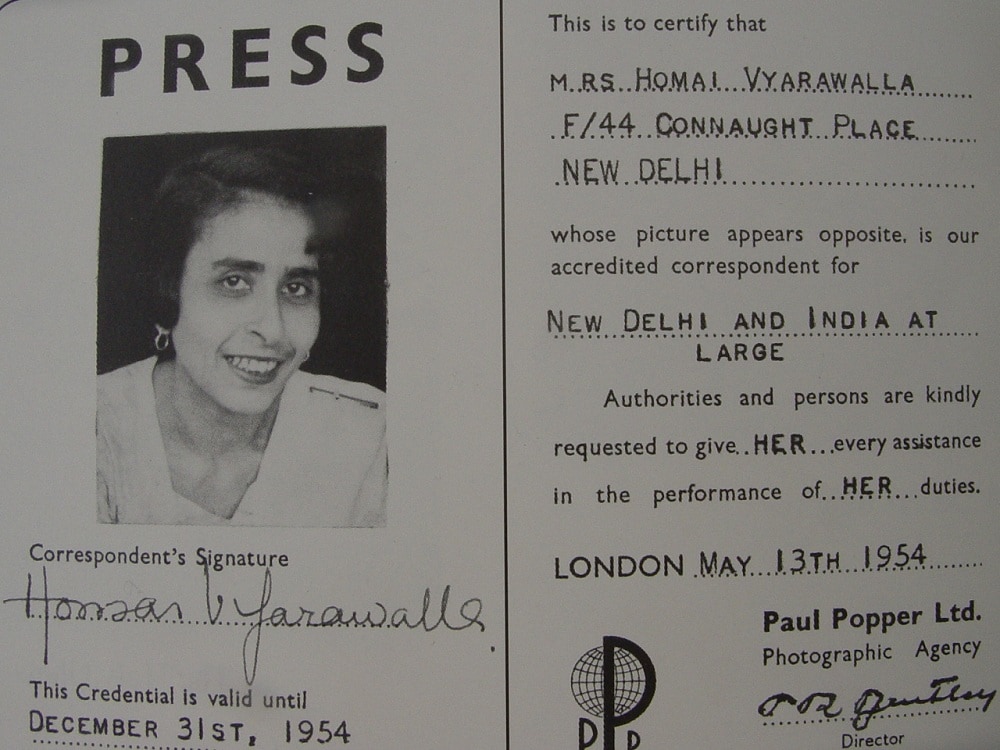

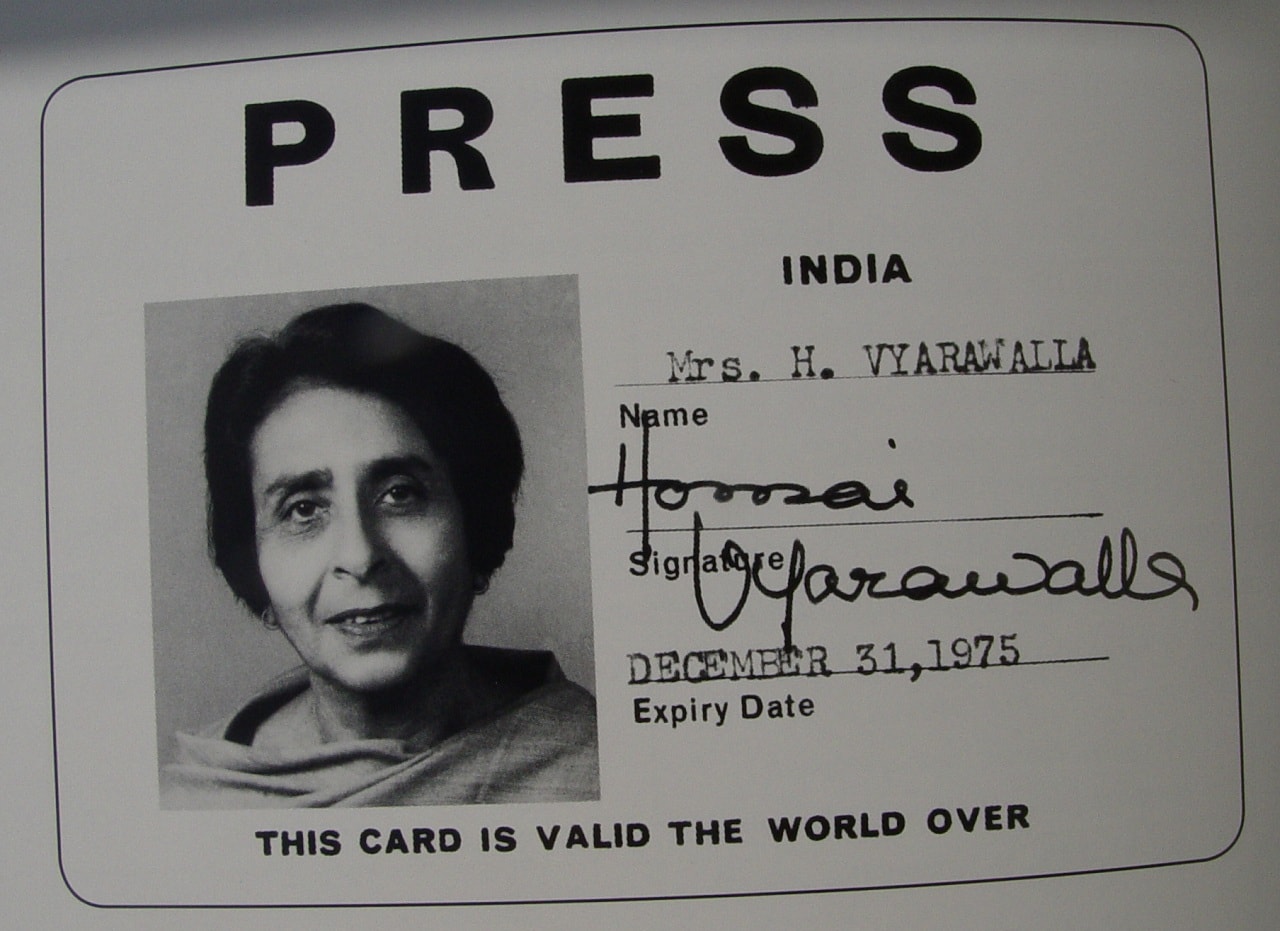

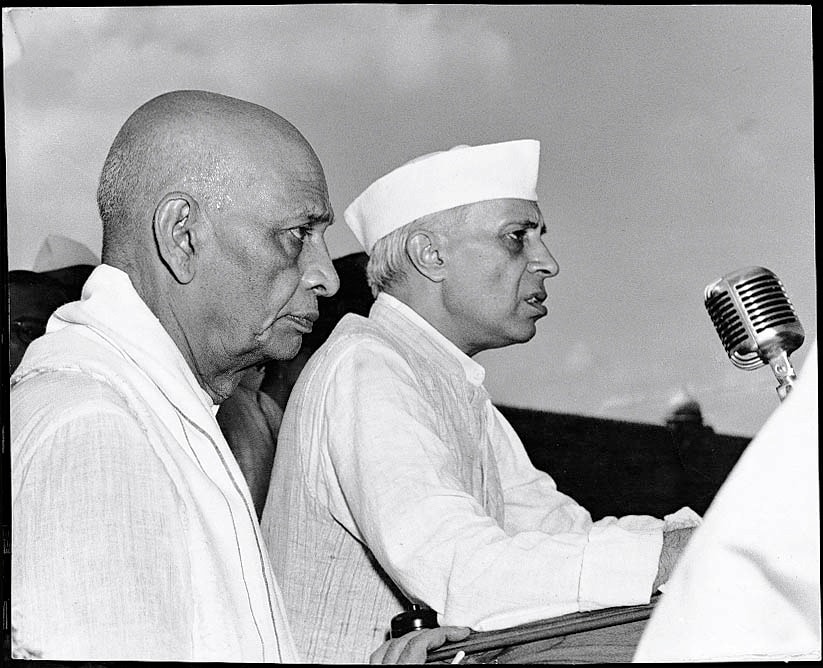

“I remember my first shot in 1938. A group of women from the Women’s Club had gone for a picnic party and I photographed them. The first published pictures were in The Bombay Chronicle and I was paid Re 1 in cash for each,” she told me.Soon, Vyarawalla started freelancing for The Illustrated Weekly of India and later moved to Delhi in 1942 where she was hired by British High Commission (then known as Far Eastern Bureau of British Information Services) as a photographer for Rs 450 a month. That changed everything. She became a permanent fixture and most of her photographs were published under the pseudonym Dalda 13 – the name stemming from the fact that her birth year was 1913, she met her husband at the age of 13 and her first car’s number plate read DLD 13.Mirth often accompanied momentous. To attend a high-profile function at the Government House (now Rashtrapati Bhawan), Vyarawalla rummaged her closet and decided to stitch a new blouse for her beige saree. She hand-stitched the sleeves and forgot to run it through the sewing machine. When she tried a top-angle shot, the seams cracked open. Without a second thought, she ripped the hand-stitched sleeves, shoved them in the purse and went back to photography.That was not the only goofy moment in the long career. Earl Warren, the then chief justice of US, was on a visit to India along with his wife and Time Life had instructed her to go wherever Warren went. She did that and while shooting them with the Taj Mahal as a backdrop, she took two steps backwards and fell into the canal.On another occassion, while covering a Mahayagna she had to take the pontoon bridge to go to the other side of Yamuna. The crowd surged, the bridge broke and she fell in the Yamuna only to be rescued by a security official. One day while shooting the Shah of Iran and his wife in Delhi, a fat photographer fell on Vyarawalla and together they almost knocked off Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan.After nearly 35 years of capturing World War II, India’s freedom struggle and independence, the rich and the chic, the menacing and the graceful, by 1960s, Vyarawalla was getting disillusioned with politics and politicking and soon after the death of her husband, she mothballed her cameras. Never to pick it again.“I lived a fulfilling life and if I were to relive life, I would do it exactly the way I did.” Those were her last words to me as Homai Vyarawalla smiled and one impish curl fell on her cragged forehead. So many years after our meeting and her death, I still want to borrow the grit of India’s first female photojournalist.

Preeti Verma Lal is a Goa-based freelance writer/photographer.