For 31 years after his death, Homi Bhabha’s office room was unoccupied

The secular condolence ceremony for Homi Bhabha of which no photographs were found has remained firmly etched in the scientists’ memory, and the religious one was forgotten.

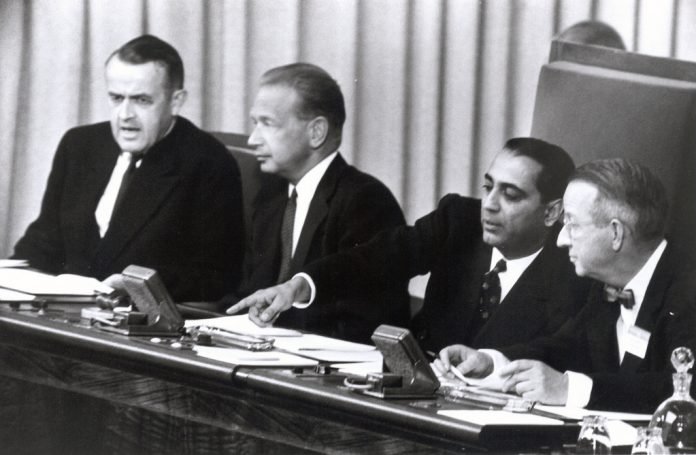

On 24 January 1966, Homi Bhabha, physicist and founder of India’s nuclear programme, died in a plane crash. The Kanchenjunga — a Boeing 707 aircraft — had crashed into the Glacier des Bossons of Mont Blac at 4,807 metres. Bhabha was on his way to Vienna to attend an Advisory Committee meeting of the International Atomic Energy Agency.

Conspiracy theories about the crash being triggered by a bomb circulated then, as they do even today. But how was the news received in the two institutions he founded in Mumbai? With deep distress and a numbing sense of disbelief that remains even now, decades after the event.

The institute had organised a condolence meeting almost immediately. And those who attended it recalled that Professor Rustom Choksi spoke. He was a member of the Tata Trust as well as the Council of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), which Bhabha had founded in 1945. The resolution that was passed spoke of Bhabha’s patriotism, his leadership and his efforts “to build with unremitting toil and exalted vision that nobler India in which skilled technology in the service of man would give to the lowliest among us the beginnings of a decent life”. These fine sentiments perhaps served to hold in check the intense anguish that many of those present felt.

The secular condolence ceremony of which no photographs were found had remained firmly etched in memory and the religious one had been forgotten.

Among the scientists, there seemed to be a slight sense of embarrassment about the religious ceremony being performed inside the hallowed portals of a science institute. Almost as if there was a schism between the two worlds that the two ceremonies represented. When pressed, many of the scientists told me that the Parsee ritual was only held to honour the wishes of Bhabha’s mother (who was also the daughter of Ruttonbai and Framji Panday), Meherbai. She was close to many of the scientists at the institute. What came as a surprise was that she was close to some of the workers too who went to see her regularly and who met her even after Bhabha’s death.

As G.V. Vasudevachar, Bhabha’s laboratory assistant who had moved from IISc Bangalore to TIFR in 1945, recalled, Meherbai had said, “Vasu, Homi told me he would be back soon. Now he won’t come back.”

Indeed, the personal dimensions of the institution-building came through sharply in many recollections. But institutional memory had replaced such personal stories with official narratives about science and nationalism. In 1967, an exhibition on the life of Homi Bhabha was put together by his institute and displayed at Royal Society London. Later, this exhibition was put up in the auditorium foyer of TIFR. The auditorium was named the Homi Bhabha Auditorium and inaugurated by then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi on 9 November 1968.

What lurked beneath such objective acts of institutional commemoration was the fact that Bhabha’s death had triggered inconsolable grief that was individual, subjective and only privately expressed.

Unnoticed by the world outside, another incident, deeply significant to the life of the institution, was passed over in silence. Bhabha’s office at TIFR was never occupied by the directors who succeeded him. I learnt from Professor M.G.K. Menon, who became the director when Bhabha died, that he had felt emotionally unprepared to occupy the space where he had worked with Bhabha. Menon’s successors too had a similar response. The office remained unoccupied until Professor S.S. Jha became director in 1997.

Bhabha’s office with its furniture was moved into a museum-ised space in the auditorium foyer. Thus, 31 years after his death, Bhabha’s office on the 4th floor of TIFR was once again occupied by the director of TIFR. Bhabha’s desk, the bookshelves, his Eero Saarinen Tulip chair could now be viewed through the enclosing glass wall, evoking a strong and haunting absence.

What do the forgotten ritual and the unoccupied office tell us about institutions and their commemorative acts? Forgotten narratives often linger beneath official ones, that private reflections offer explanations very different from what are visible, public actions. But they also alert us to the inability of institutions to acknowledge and express grief and then engage meaningfully with the legacy that they have inherited.

Indira Chowdhury heads the Centre for Public History at the Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Bengaluru. She wrote a book titled ‘Growing the Tree of Science: Homi Bhabha and the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research’ in 2016.