First Dastoor Meherjirana Library: The Oxford of Gujarat

I never saw such a fine collection in a small town, and it does honour to the generosity of the donors and to the zeal for instruction of the Parsi population at Navsari. This visit will remain one of the best remembrances of my short occasion in the Parsi mofussil.

This inscription, the first entry in the guestbook of Navsari’s 145-year-old First Dastoor Meherjirana Library, scrawled in the lithe, oblique hand of James Darmesteter, a French Orientalist, translator and scholar of Iranian philology and Zoroastrianism, dates back to January 1887. The son of a Jewish bookbinder, Darmesteter was elected chair of Iranian languages at the Collège de France in Paris in 1885. He travelled to India the next year to trace the origins of a few Pashto ballads. His 11-month-long itinerary included excursions to the Punjab, Peshawar and Abbottabad and brief halts in Bombay (now Mumbai) and Navsari. An article he wrote on Bombay’s oldest French library, Le Cercle Littéraire Bibliothèque Dinshaw Petit, located on Forbes Street (today V.B. Gandhi Marg in the Kala Ghoda precinct), published in Les Journal des Débats in November 1891, testifies to his visit to this thrumming commercial centre of colonial India. But what drew Darmesteter to Navsari, a sleepy town in Gujarat surrounded by chikoo plantations, about 250km from Bombay?

Centre of learning

Centre of learning

I first came to Navsari in 2015, looking for a house that had belonged to my paternal great-grandfather. The nationwide construction boom is visible here too as the town steadfastly embraces change—pastel-hued, one-storeyed houses with spacious otlas (porches) are now transforming into modest apartment blocks; grocery shops are making way for ritzy showrooms. When I went back in August this year, I made sure to stroll through the town, taking in the details—dense gulkand ice cream at the Yazdan Cold Drink House, the swathe of green that is Tata Baug, and the striking façade of the library on an arterial street.

It is believed that Parsi migrants settled in Navsari in the 12th century, some 400 years after their arrival on the shores of Sanjan. It is also believed that Navsari has the oldest existing fire temple outside of Iran, the Vadi Dar-e-Meher, consecrated between 1140-60—the exact date is contentious. It is revered as the most important centre of priestly learning in India, especially for those ceremonies that ordain priesthood. Navsari is so important to Parsis as a centre of learning, with the Vadi Dar-e-Meher being a key centre for initiation into priesthood, that in his Gujarati book Tawarikh-e-Navsari (1897), historian and sociologist Sorabji Mancherji Desai compares it to Oxford University.

The library’s repository of manuscripts is impressive and wide-ranging—it includes sanads belonging to the Mughals; an Indo-Persian cookbook titled Kitab al Ma’qulat va’l Mashrubat; recipes from Unani medicine in Gujarati; Outlines Of Zend Grammar in Avestan; and copies of the 19th century illustrated and lithographed Shahnameh, a Persian epic by Firdausi first completed in 1010. It is also home to printed publications such as volumes of Parsee Prakash (see box), a record of the obituaries of prominent Parsis; the collected works of Friedrich Max Müller, including Chips From A German Workshop and India: What Can It Teach Us?; and parts of Harmsworth Popular Science, a British fortnightly on science and innovation first published in 1912. There are books on science, philosophy and popular literature, autobiographies and encyclopaedias. The library is often open until midnight, with students using the reading room free of charge. It is a space open to members of all communities.

The Meherjirana Library has attracted scholars from across the world—Australia, France, Germany, Iran, Japan, Spain, the UK and US. “We have hosted 56 scholars in the last six years,” says Antia. A three-day conference in January 2013 saw the library play host to scholars such as author Amitav Ghosh, historian and pedagogue Dinyar Patel and a researcher from the Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies, Anton Zykov, and was an occasion to showcase a selection of the meticulously conserved manuscripts. The library has also been working closely with Prof. Alberto Cantera and his team of researchers at the University of Salamanca, Spain, to digitize important Avestan manuscripts through the Avestan Digital Project (see box).

The story of its name

The name of the library can be traced to one of the manuscripts it holds, the Mahyarnama, a versified Persian biography of Meherji Rana. A boy named Mahyar Vacha, later known as Meherji Rana, was born in Navsari in 1514. Adopted into the lineage of the Bhagaria group of Parsi-Zoroastrian priests of his paternal uncle Vaccha Jesang, Meherji Rana soon won recognition for his devoutness. According to a translation of the Mahyarnama, an excerpt of which appears on the official website of the library, “Meherji Rana was chosen by the Mughal governor at Surat to have an audience with the Emperor Akbar…During his stay at the court from 1578-79 AD, Meherji Rana impressed the emperor so much that according to the Mughal historian ’Abd al-Qadir al-Bada’uni, the Emperor ordered his vizier Abul Fazl to keep a fire burning day and night at the court. Meherji Rana thwarted the sorcery of a Hindu priest named Jagatguru, who had caused a plate to ascend into the sky, appearing like a second sun. Before Meherji Rana left court he was given a land grant by the Emperor, in an area called Ghelkhadi, near Navsari.”

A firman or sanad (deed) was issued under Akbar’s seal and signed by Abul Fazl. Today, it sits framed in the administrative office of the library. Restored with the support of the New Delhi-based Parzor Foundation, first initiated by UNESCO New Delhi in 1999 for the preservation of Parsi-Zoroastrian heritage, it was on display at the exhibition Threads Of Continuity: Zoroastrian Life And Culture, held at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) in New Delhi in March last year.

Upon his return to Navsari, Meherji Rana was accepted as the head priest (vada dastur). There began a priestly lineage that continues today: On 25 January 2010, Kaikhushroo Navroze Dastoor was chosen as the 17th Dastoor Meherji Rana, and currently serves as the head priest.

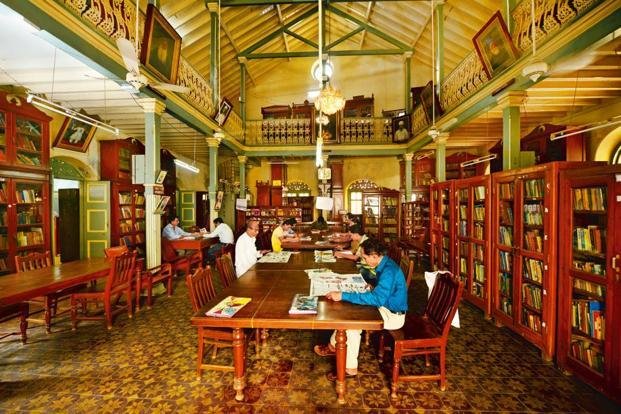

A stately structure in cadet blue and white, the library is located a short distance from the Atash Behram (fire temple). A flight of stairs leads to the main reading room, where empty chaises longues dot the periphery. In the afternoon, the space sinks into sepulchral silence, save for the rare cry of a hawker ferrying wood apples and sweet-and-tart carambola (kamrakh) on a pushcart down the street. The air is filled with the musky scent of leather-bound covers. A wrought iron spiral staircase in one corner leads to more cupboards chock-full of books. A member of the staff arranges well-thumbed dailies on a pigeon-hole wall shelf. Students pore over tomes to prepare for entrance examinations, patrons go through newspapers with hawk eyes.

A stately structure in cadet blue and white, the library is located a short distance from the Atash Behram (fire temple). A flight of stairs leads to the main reading room, where empty chaises longues dot the periphery. In the afternoon, the space sinks into sepulchral silence, save for the rare cry of a hawker ferrying wood apples and sweet-and-tart carambola (kamrakh) on a pushcart down the street. The air is filled with the musky scent of leather-bound covers. A wrought iron spiral staircase in one corner leads to more cupboards chock-full of books. A member of the staff arranges well-thumbed dailies on a pigeon-hole wall shelf. Students pore over tomes to prepare for entrance examinations, patrons go through newspapers with hawk eyes.

Keeping up with the past

In 1923, the library commissioned Ervad Bamanji Nasarwanji Dhabar, a scholar of Zoroastrian studies and Avestan and Pahlavi, to catalogue the collection. They had 469 manuscripts. This was titled “Descriptive Catalogue Of All Manuscripts In The First Dastur Meherji Rana Library”, Navsari, known colloquially as “Dhabar’s Catalogue”. In 2008, a comprehensive catalogue of all the manuscripts received after 1923 was compiled by Firoze Kotwal, a community scholar-priest and adviser to the Unesco-Parzor Foundation project of manuscript conservation, Daniel Sheffield, a postdoctoral fellow and scholar from Princeton University, and Bharti Gandhi, the librarian at the time. They listed the 157 manuscripts that had been acquired over 85 years.

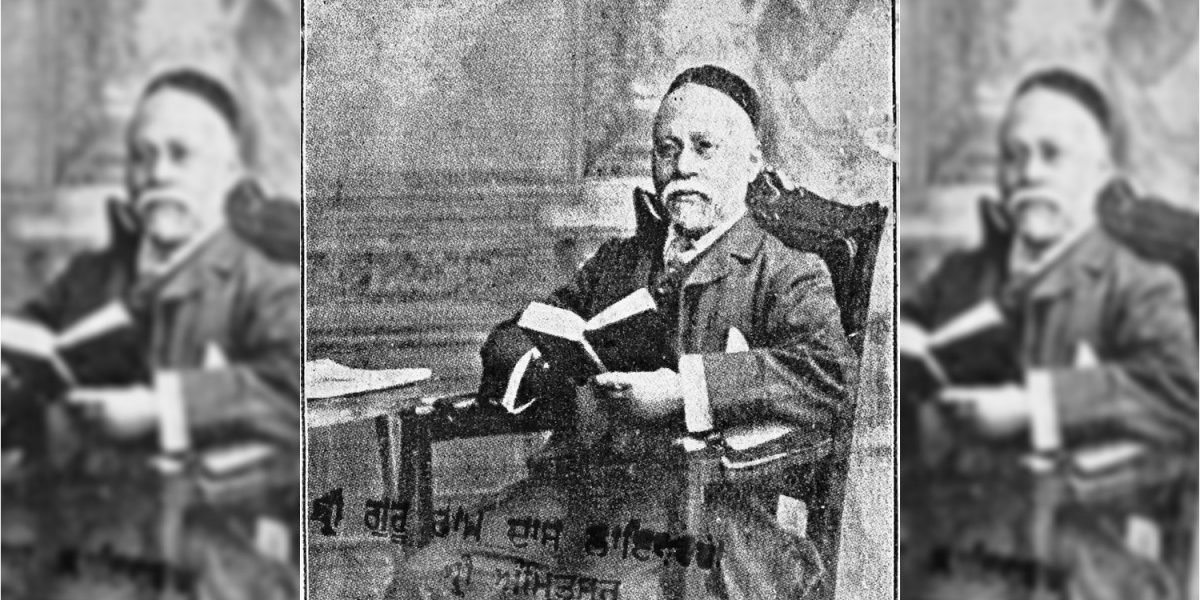

“The collection of manuscripts was built gradually as a result of contributions by various families and individuals from Navsari and elsewhere,’’ says Antia. Several manuscripts were donated by the Meherjirana family itself. The largest was by Dastoor Erachji Sorabji Meherjirana (1826-1900), a descendant of Mahyar and a remarkable scholar who mastered the art of writing Persian manuscripts by hand at a young age. He was appointed librarian at the Mulla Feroze Library in the early 1860s, and simultaneously assigned the task of copying a number of manuscripts in Avestan, Gujarati and Persian. According to Kotwal’s paper, A Treasury Of Zoroastrian Manuscripts: The First Dastoor Meherjirana Library, Navsari (2011), Dastoor Erachji not only made copies for the Mulla Feroze Library but for himself as well. When he donated his collection to the Meherjirana Library, there were more than 75 manuscripts in his own hand. He is also recognized for having compiled the first Pahlavi-Gujarati dictionary in 1869. More recently, the holdings of the library have been further enriched by the acquisition of manuscripts from families living in Mumbai, from Kotwal’s collection, as well as from non-resident Indians.

The exactitude of the “makers” of Zoroastrian manuscripts—the calligrapher, illustrator and binder—was of prime importance at each stage of creation. The same importance can be extended to the role of the conservator. The important manuscripts conserved at the library by the INTACH Conservation Institute, Lucknow, include two illustrated volumes of the Shahnameh, the Sikandar Nameh of the Persian poet Nizami, Jamaspi manuscripts in Gujarati, a Persian vanshavali (genealogical chart), and several firmans.

First undertaken in February 2006, INTACH’s ongoing conservation of rare manuscripts was planned in phases. A temporary climate-controlled laboratory was set up inside the library annexe. Twenty-five phases of curative conservation have since been completed, and 88,417 folios restored. Around 698 objects, including firmans, scrolls (one is 18ft long), vanshavalis, oil paintings and photographs were given a new lease of life.

Mamta Mishra, director of the institute, says: “The main problem was posed by the fugitive inks used and the charred effect of the iron gall ink, which is acidic in nature. The iron gall ink is initially black in colour but on ageing, chars, turns brown, and gets transferred on the rear side of the paper.” The most common causes of wear and tear, according to Mishra, are deposition of dust and dirt on the paper, brittleness due to acidity, warping and abrasion of the folios, and ink stains. Fungus growth and infestation by insects take a toll too. Defective repair using acidic paper too leaves splodges of adhesive on the folios. The pages are very delicate—there is a fearful crackle of paper; it crinkles at the slightest touch.

Yet the greatest challenge comes from the climate, which prompted the microfilming of almost 90,000 pages, a project funded by the Parzor Foundation. Other donors include the FE Dinshaw Trust, the Pirojsha Godrej Foundation and the World Zoroastrian Organisation Trust.

Membership of the library has grown. It currently has about 400 members, 100 of them lifetime members. The fee is modest—Rs240 for an year-long membership, and Rs5,000 for lifetime membership.

Acquiring funds is a recurrent challenge faced by the library, but its operation and upkeep are far from the bureaucratic malaise that plagues similar institutions in the country, owing to the dedication of trustees and staff. “There is endless conservation work to be done and more manuscripts await treatment,” says Mishra. “They are then beneficial to the research scholars who visit the library from time to time.”

‘Parsee Prakash’

Born in Bombay in 1849, Bomanji Byramjee Patel collected newspaper cuttings of major events in the Parsi community of Bombay and the world. When he died in 1908, it is believed he left behind about 200 scrapbooks of cuttings. But a few benevolent Parsis had recognized its archival value earlier. They helped Patel establish a periodical that would eventually become a vital source of reference for the general public. It was named ‘Parsee Prakash’, and comprised unabridged obituaries of members of the community; letters drafted by renowned Parsis; government deeds; and even the eloquent writings of itinerant travellers. While the first volume, comprising 11 parts, was published in 1888, the second was put together after his death by his wife. Thereafter, Rustam Barjorji Paymaster, a Mumbai-based scholar and poet, was hired to edit and compile volumes (3-7), published by 1942. Following Paymaster’s death in 1943, efforts were made to renew the periodical, and by 1973, another four volumes were published, recording events until 1962. It is believed that an additional volume (12) served as a comprehensive index to the entire set. Most of the volumes are at present at the Meherjirana Library, the KR Cama Oriental Institute in Mumbai, and the library of the Bombay Parsi Panchayat.

Conservation of the KhordehAvesta from 1601

he INTACH restoration process salvaged a copy of the Khordeh Avesta, a prized manuscript of the library that is over 400 years old. The team from the department of preservation at the Royal Library in Copenhagen, Denmark, led by conservator Hanne Karin Serensen and book-binder Hanna Munch Christensen, received it in two volumes: one comprising 299 folios, and the other, 250 folios. Handwritten in red and black ink, it was partially restored by the late Nicholas Hadgraft in Cambridge, UK. The text arrived in Copenhagen in poor condition—the manuscript was unbound, the pages yellowing and infested. The red ink had corroded in portions, and the paper was prone to foxing, or the appearance of reddish-brown rusty blotches.

The restoration process

- Strips of thin Japanese paper were used to secure the insect-damaged parts

- The adhesives were chosen to suit a warmer climate. In some places, wheat starch was used to create stronger bonds.

- The loose pages were rejoined with strips of paper from both sides, the quires gathered and sewn together.

- The book block was sewn on and woven with cotton-linen tape, and the sewing thread used was a linen yarn from Sweden.

- The spine was glued with synthetic adhesive Evacon-R.

- The end bands were made by hand and sewn with linen thread on a thin rope, followed by a piece of tape to further strengthen the structure.

- Preparation of the leather cover involved paring with a hand-knife, to make the edges thin enough for a gathering which appears as discrete as possible.

- The box was lined with cotton flannel, the spine covered in the same leather as the cover, and the lid and sides dressed with red-coloured bookbinders’ cloth.

The manuscript is now nestled in a cabinet under the watchful gaze of the librarian. It is available on request, and one is expected to wear a pair of gloves while leafing through its painstakingly restored pages.