The Parsis fighting to stop their culture dying out, and why it appears doomed

With only 100,000 Parsis left, 200 of them in Hong Kong, and four dying for every one that’s born, a quirky community known for its immense contributions to the city and to India appears bound for extinction

With only 100,000 Parsis left, 200 of them in Hong Kong, and four dying for every one that’s born, a quirky community known for its immense contributions to the city and to India appears bound for extinction

The birth and death notices in Parsiana tell a stark story. The June edition of the Mumbai-based magazine for Parsis lists two births and 46 deaths in the city. Perhaps June was not a typical month, but India’s most illustrious minority are aware of the numbers – for every Parsi born, four die – and know what they foretell.

A copy of Parsiana is given to me by Rati and Yezad Kapadia, a retired Parsi couple in their 70s who are clearly still in love, as I’m leaving their home in Gurgaon, just outside Delhi.

“What can I say? You can’t argue with numbers,” says Yezad, who heads the Delhi Parsi Anjuman, a social organisation in the Indian capital. “What other possible interpretation is there of the figures except that we are going to disappear? It is a fait accompli. In 50 years’ time, there will be no Parsis left in India.”

FROM 114,000 IN THE 1940s, Parsi numbers have plummeted, falling by approximately 10 per cent a decade. In 2011, census figures showed the rate had accelerated to 18 per cent, and there are now just 57,000 Parsis left in India, most of them living in Mumbai. In New Delhi, only 750 remain. The global figure is about 100,000 – 200 of whom call Hong Kong home.

FROM 114,000 IN THE 1940s, Parsi numbers have plummeted, falling by approximately 10 per cent a decade. In 2011, census figures showed the rate had accelerated to 18 per cent, and there are now just 57,000 Parsis left in India, most of them living in Mumbai. In New Delhi, only 750 remain. The global figure is about 100,000 – 200 of whom call Hong Kong home.

Historians and anthropologists in the future may wonder how a people that has excelled in the fields of business, medicine, science and the arts came to such a pass. They will no doubt question how a group who, with the rise of Islam between the eighth and 10th centuries, fled Persia for India to preserve their kind and their ancient religion of Zoroastrianism; who enriched their new homeland to such a degree that they were described by the author Amitav Ghosh as having “essentially created modern India”, with their factories, mills, hotels, steel plants, hospitals, educational institutions and research institutes; who showed Indians how to be philanthropists; who established business empires such as the Tata Group; and who shaped early Bollywood, reached the point where they could not make enough babies to perpetuate their communities.

“Parsi women are highly educated and high achievers. Not many want to leave their careers to start a family early,” says Kapadia, who is a priest and often travels to Hong Kong to perform the Navjote (the initiation ritual) and wedding rites in the city. “For a long time we thought our daughters would never marry at all.”

Eventually, Rukshna married, but when she did so it was to a Hindu. The couple have two sons who, according to the strict interpretation of religious laws, are not Parsis, because their father is not. Jeroo has not married. Both daughters live abroad, Rukshna in Hong Kong and Jeroo in Auckland (which is home to 1,200 Parsis) in New Zealand.

These circumstances broadly capture the plight of the people as a whole. About 30 per cent of Parsis never marry and those who do wed late and have no children, or have just one or two. Many marry non-Parsis or migrate.

“We know the solution is for couples to have four or five children but young Parsis don’t want so many,” says Minoo Shroff, a retired corporate executive who headed the 350-year-old Bombay Parsi Punchayet for 20 years. “They want a good quality of life, good homes, holidays and the best education for their children, and this is only possible if they have one or two. They think of themselves as individuals and not of the community and its needs, which is, on one level, understandable.”

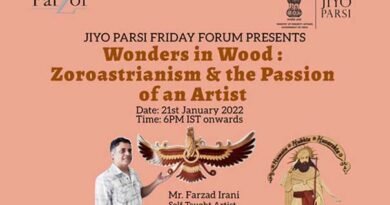

The Bombay Parsi Punchayet has tried various schemes to encourage procreation, which have included offering housing subsidies and cash allowances to young couples. Alarmed at the prospect of losing its most dynamic minority, even the Indian government has taken action, in 2013 initiating a scheme called Jiyo Parsi (Live Parsi) to provide free fertility treatment. Speaking at its launch, the then minister of minority affairs, Najma Heptulla, said, “This is a small step to pay our debt to the Parsi community for their contribution to the country. We cannot afford to lose this community.”