Trial by fire: Women chefs and the challenges they face in kitchens

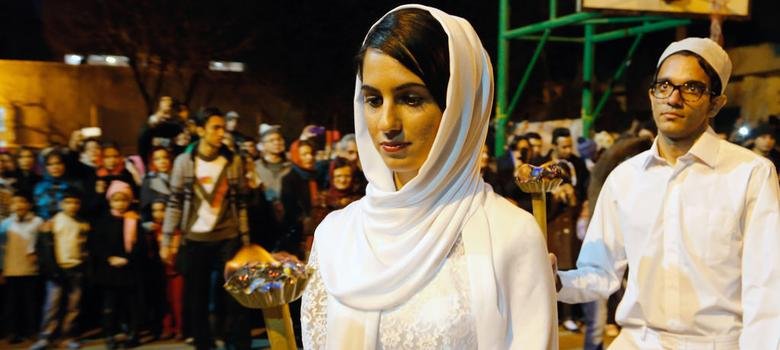

Anahita Dhondy, chef manager at SodaBottleOpenerWalla in Delhi, says she has had to learn to be forceful about her inputs, repeat herself and stand firm

Anahita Dhondy, chef manager at SodaBottleOpenerWalla in Delhi, says she has had to learn to be forceful about her inputs, repeat herself and stand firm

Sometimes it’s an offer of help — ‘let me take that, it’s too heavy for you’. At other times, it’s more overt — instructions are met with a grim silence, audible whispers talk of ‘teaching her a lesson’.

It’s hard work fitting in if you’re a woman in a professional kitchen — one of the last remaining male bastions in the white-collar world.

In Chennai, 23-year-old Komal Sunder Rajan was singled out on her first day of training at a five-star hotel kitchen and asked if she could cut an onion. “No one else was asked,” she remembers. “I just looked at the instructor and said, I can cut an onion.”

In Guwahati, entry-level chef Kavya Gupta* says she has endured open hostility ever since she began her career eight months ago. “The men tell me I talk too much. They say I won’t be able to perform at their level,” says the 26-year-old. “I’m not allowed to work on main courses. If I offer an idea, it is met with silence.”

Gupta says that the discrimination has left her disheartened, but determined to continue. “It’s been my dream to be a professional chef, so I won’t quit, but I have been depressed, frustrated and angered by the treatment I have received — for no other reason than because I’m a woman in a professional kitchen full of men who don’t like that.”

Sexism in the kitchen is alive and kicking and it comes down to two factors – the physically strenuous nature of the work, and how male-dominated the industry is, says Vir Sanghvi, food writer and editorial adviser to the Hindustan Times. “These two factors make it a very ‘macho’ environment,” he adds. “In the metro cities, chefs tend to be well-educated and this can make things slightly easier. But there’s a long way to go before the situation equalises, and that will only happen over time as more women enter professional kitchens.”

What makes the identity of the woman in the kitchen so interesting, especially in India, is how bipolar it is, adds Smriti Godbole, a Bangalore-based sociologist who is working on a PhD thesis on indigenous foods of the Konkan region. “In the home, the woman was traditionally told her place was the kitchen. The professional kitchen, however, was never associated with femininity or women’s work, but with making money, ” she says. “It then became a male zone, and still remains one — in many cases.”

For a long time, Godbole adds, women who wanted to cook outside the home navigated this by writing cookbooks or being ‘home chefs’, catering for special events or supplying packed lunches.

“When I started out in 1975, we didn’t have a single woman working full-time in our kitchen,” says Rahul Akerkar, the chef and restauranteur behind the Indigo chain of restaurants. “That has changed now, for a couple of reasons. One, professional cooking has emerged as a legitimate and ‘honourable’ profession, whereas earlier it was just seen as hard labour. Second, the role of women culturally has changed, so they’re not hesitating as much to venture into traditionally male arenas.”

It also helps that there are now mentors and role models to light their way. In Mumbai, Pooja Dhingra has launched Le 15, a successful patisserie chain. In Delhi, Megha Shah is head chef at Lavaash by Saby, a one-of-its-kind Armenian restaurant. In Chennai, Aloka Gupta runs The Bayleaf, one of the city’s most iconic restaurants. In Bangalore, Tori Macdonald is the head chef at The Humming Bird cafe and bar, one of the city’s most popular music venues.

Macdonald is one of those who found the constant offers of help from her team of 12 men discriminatory and oppressive. “I was forced to enact rules to curb this problem,” she says. “Now, nobody is allowed to help me unless I ask them.”

Click here to read more on Hindustan Times