Shaheen Mistri’s Teach for India: Read, Baby, Read

It’s 5 p.m., but even at this late hour, the 50-some sixth-graders in Rushali Daga’s Mumbai classroom are bopping in and out of their seats. It’s the last class of the day; the kids belong to the second shift of students to attend classes — there aren’t enough seats or teachers to handle all the students during the same hours. The kids, oblivious to this, have a boatload of questions for the pen pals they’re writing to, students at a school up north: What do you like to eat? What is your room number? What is your favorite color? Will you make friendship with me?

We’re in the Parel neighborhood, down the road from some of the city’s gleaming office buildings, but these are not the children of such businesspeople. They’re students in one of India’s troubled government schools, where, according to UNICEF data from 2012, around half or fewer of students who start primary school make it to secondary education. And while these kids aren’t asleep and are engaged — better than expected — the teacher’s boss, Shaheen Mistri, sits at the edge of the room with a subdued smile. She is not entirely pleased.

We’re in the Parel neighborhood, down the road from some of the city’s gleaming office buildings, but these are not the children of such businesspeople. They’re students in one of India’s troubled government schools, where, according to UNICEF data from 2012, around half or fewer of students who start primary school make it to secondary education. And while these kids aren’t asleep and are engaged — better than expected — the teacher’s boss, Shaheen Mistri, sits at the edge of the room with a subdued smile. She is not entirely pleased.

The big idea, much as it is in the U.S., is to balance the grassroots stuff with the high level, graduating alumni who stay in India and work on educational change.

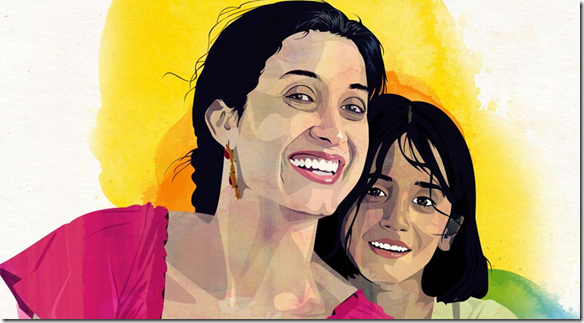

Mistri, 44, is the ambitious founder of Teach for India, or TFI, a nonprofit that takes fairly green teachers (Daga was a trained engineer before this) and throws them into the messy fray of understaffed and infrastructure-less classrooms. It’s pretty much the same model as the well-known Teach for America program in the U.S. that works with thousands of kids across the country. But, as with many American ventures that have their versions in India — see Bollywood or e-commerce — the model here looks quite a bit different.

For one thing, TFI deals with some of the most difficult teaching conditions in the world, with only one out of every 10 students in India graduating high school. Here, teachers can be apathetic and classrooms lack furniture; in rural parts of the country, you might even teach under a tree, says Urvashi Sahni, founder and CEO of Study Hall Educational Foundation and a fellow with the Brookings Institution think tank. Though India produces some of the world’s top engineering and medical graduates, it’s famous for nonconceptual rote learning, even in some of its better schools.

On the one hand, it’s an obvious story: third-world country, rough schools, etc. On the other hand, it’s an easily hidden narrative, in part because of Indians like Mistri: sophisticated, well-off, equipped with cosmopolitan accents and a nonchalant grace with which they navigate the working world. The Mumbai-born Mistri, who attended cushy schools around the world, lives not too far from here, in the lovely Worli neighborhood, which looks out onto the water. She has two daughters, ages 11 and 16, who attend private school. “I don’t think there are any really good schools in Bombay,” she says.

Where Mistri lives, just as in Parel, nouveau luxury sits next to sprawling slums. Mistri, though, is native to the “constant contrasts” of rich and poor in India. She remembers it from visiting her grandparents as a child, and as a teacher for 12 years, occasionally working in schools where there was no running water and just two toilets. She’s also no stranger to the nonprofit world, having founded the well-regarded education-equity nonprofit Akanksha over two decades ago. As the daughter of a Citibank executive, she swung between schools from moneyed Greenwich, Connecticut, to Jakarta to Athens to Beirut to India itself. Mistri says Mumbai was the first place she really felt at home.

Her recollections of those early days, and her assessment of classrooms like Daga’s, though, is less a soft look at what we’ve given them and more exigent: “In some ways,” Mistri says of her first years as a teacher, “I don’t think my expectations were high enough.” While the sixth-graders write their letters, we sit on a ledge in the hallway, where various kids stop to ogle us. Mistri is an exciting stranger in their midst. She wears a white paisley shirt and brown pants and sports summery orange toenails — one little girl obsesses over that pedicure.

Mistri oscillates between practical and almost yogic language when she describes training her teachers, which number over 1,100 and work in more than 300 schools. She sets a tone within the organization that demands not only competence but also introspection. At TFI’s five-week summer training institute, young teachers get emotional, are told to “live the values,” Mistri says, and work through the “internal journey” of becoming leaders. The big idea, much as it is in the U.S., is to balance the grassroots stuff with the high level, graduating alumni who stay in India and work on educational change.

Mistri interrupts our conversation to ask the children what they are learning. They say, math, books, etc. She quizzes them. A few grow bored and wander away. She persists. What, she wants to know, is the class motto? “Read, baby, read!” one girl says. A few join in, saying in unison, “You’ve got to read, baby, read.” The school motto? They recite, lively but rote, “Knowledge is power.”

Published on Parsi Kahabar