A Rendezvous With Ancient Persian Kings and Poets in Shiraz, Iran

Arriving at Shiraz International Airport – the largest in Iran’s southern region of Pars province – I join hundreds of foreign and domestic travelers who eagerly await to explore their rendezvous with ancient history – revisiting Persian Kings and poets memorialized here as national and world treasures.

As Iran’s fifth most populated city, Shiraz, since the 13th century, has been a leading center for Persian arts and literature. Cradled by Zagros Mountains, the city is the custodian of Persia’s ancient relics; from the tombs of Persian Kings and world-renowned beloved poets, to the remnants of the ceremonial capital city of the Achameneid Empire, the Persepolis – Shiraz is also the third largest religious city in Iran, after Mashhad and Qom.

Famed for inlaid mosaic artistry and carpet weaving industry, Shiraz boasts a large oil refinery, a highly productive electronic industry, and Iran’s first solar power plant and wind turbine.

Home to vibrant and active Jewish and Christian-Armenian communities, Shiraz is the birthplace of the co-founder of the Baha’i Faith -Siyyid ‘Ali-Muhammad, or Ba’b (1819-1850) who in 1844 announced his new divine revelation and turned Shiraz into a Bahai’ holy city. Shiraz also vaunts a reputable wine making history dating back to 7,000 years with the oldest sample of wine in the world found in clay jars during archeological digs in a Neolithic village in northern Zagros Mountains.

There are multitude of “must-see” sites in the city of Shiraz itself – as well as its environs. Most tourist sites and palaces charge a minimal fee which is higher for foreigners than the natives.

At the top of the list of “must-see” sites in Shiraz are the tombs of the city’s two most beloved poets – Hafez and Saadi.

Beyond the congested downtown traffic, on the northern edge of the city’s Golestān Street – a cobblestone street hugged with expansive gardens and ancient walls of the city limits – sits Aramgahe Hafez – the Mausoleum of Hafez (1315-1390) or Hafezeeye as natives call it.

Born into a city famed for its poetry and literature – wine, flowers and gardens with rectangular reflecting pools that mirror aromatic, aesthetically landscaped gardens – Hafez’s poetry reflects Sufi wisdom (Islamic mysticism), admirations of the beloved, the pleasures of wine and the serenity of the flower-laden gardens where he often took refuge. One of the great figures of Sufism — Hafez’s love poems – Divan e Hafez – is commonly used for fortune telling or as natives call it – Fal ‘eh Hafez. Every Iranian home has a volume as the “go-to” source for what the future holds. Making a wish, holding the book closed in both hands, then splitting it open, the seeker is to read the poem on the facing page to find words of wisdom.

Capitalizing on this tradition, city vendors line up at the entrance gates to Hafezeya with boxes of poetry leaflets for sale. For a mere 25 cents, a colorful canary selects a special poem with its beak and you’re off to read what the future holds for you.

Inside the gates, serene gardens of aromatic flowers and tall poplar trees reflected in the stretched out rectangular pools, lead to a columned terrace adorned with verses of Hafez’s poetry where Hafez’s tomb comes to full view.

The French archeologist and architect, Andre’ Godard, restored and designed the memorial in 1931 by raising the tomb, encircling it with five steps and eight, ten-meter high columns which hold a copper dome atop the marble covered tomb. The dome, symbolic of a Sufi’s hat, is designed with exquisite mosaic.

Considered the undisputed master of Ghazal – a one-rhymed lyric poem -Hafez’s poetry is still recited, memorized and sung throughout Iran and the world. By the brick walls encircling the gardens and the Tomb crowds of Hafez admirers and tourists take refuge in the serenity of the garden or drop by the cramped gift shops and small inner courtyards.

A short cab ride from Hafezeye to the north-east part of the city, sits the tomb of Shiraz’s other beloved poet Saadi (1210 – 1292).

An avid traveler who lived in different parts of the Middle East, Saadi returned to his birthplace to become one of the masters of the classical literary tradition with such poetry volumes as Bostan (orchard) and Golestan (rose/flower garden).

A famed verse from Saadi’s poem is inscribed at the entrance to the Hall of Nations in New York’s UN headquarters:

Of one Essence is the human race,

Thusly has Creation put the Base;

One Limb impacted is sufficient,

For all Others to feel the Mace

Gardens have always been a centerpiece of Persian architectural design and Shiraz certainly has no shortage of magnificent gardens. The famed expansive Affif Abad Garden housed in the city’s affluent Afif-Abad district (circa 1863) includes a royal mansion, a historical weapons museum with a magnificent Persian garden which is one of the oldest in Shiraz. A palace during the Safavid Period (1502 -1706) the army restored the entire structure in 1962 to function as a weapons museum.

At the front entrance of the palace, two canons stand retired from their ancient role of heralding the start of Norouz – the Persian New Year on Spring Equinox.

The now deposed Shah invested much into renovations of the gardens and the complex which was the monarch’s residence during the 1971 2500-year anniversary celebrations at Persepolis. The reception hall is magnificently decorated with furniture and antiques from around the world. Each room in the palace is decorated in different color schemes.

At Soufi Restaurant (Sattarkhan St.) decorated with Sufi motifs and symbols, guests enjoy traditional Persian cuisine complemented with live traditional Persian music. The restaurant offers both take-out and dining space.

Warm Sangak bread, made fresh in the restaurant’s brick oven, is served warm with Fetah cheese, mint and basil along with Salad Shirazi – a mouthwatering combination of chopped cucumbers, tomatoes, onions with mint and lemon. Soon our Entre’ of Kabob Koobideh – ground beef kebab – with grilled tomato, Zafron rice, French fries, mint, pickles and onions hits the spot.

At a nearby bakery offering local specialties and artfully decorated cakes, we complete the culinary experience with the sugary paste gelatins called Ghasmati – special to Shiraz.

But no visit to Shiraz can be complete without exploring the ancient Vakil Bazaar (built 11th century). At the edge of the labyrinth of stores and kiosks a man peeks through the gates of the Qajar era historic Agha Baba Khan School.

The school’s doors adorn ancient, traditional door knockers – one for females (on the left) and another for males (to the right).

The maze of shop stalls open to vast courtyards, centered with shallow pools and encircled with arched entryways to additional stalls, shops and restaurants. Most shopkeepers in the bazaar still use the old scales for daily commerce. Caged canaries offer symphonies of bird songs for shoppers amidst the hubbub of vendor calls and racing carts zigzagging around shoppers bargaining for goods.

Revisiting the Ancient Kings of Persia

One of the most ancient sites outside of Shiraz is the UNESCO World Heritage Site – Persepolis – or Takht-e-Jamshid – Throne of Jamshid. The ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire is set about 70 kilometers drive to the northeast of Shiraz. Persepolis is also the site of the internationally televised grandeur ceremonies of the 2500 year celebrations of the Persian Empire when the Shah of Iran crowned himself and his Queen Farah.

On the road to the ancient site, Takhte Jamshid (Persepolis) Restaurant provides an ideal refuge. The restaurant’s traditional Persian seating – on raised beds where food is enjoyed on a Persian carpet surrounded by Motakah – cylinder shaped leaning pillows – as well as modern tables are usually filled with tourists. An outdoor courtyard provides additional seating.

The first signs of Persepolis’ tall limestone columns rising high in varying lengths, scattered as though throughout a plateau, are seen from the well-paved road leading to the ancient site. From either side of the Great Wall, 111 broad, shortly distanced steps – now covered with wooden planks to preserve its original 519 BC construction — bring visitors to the main entrance of a terrace that stands nearly 20 meters above the ground level. The closely spaced stairs allowed a regal appearance to the visiting dignitaries as they ascended toward the Gate of all Nations.

Nations in this case were subjects ruled by the Empire. The Gate today stands in partial ruins with glass walls covering the already looted base where graffiti artists inscribed initials and messages. In the open air museum of archeological wonder, bellowing bull horns from small guard towers set high above, remind visitors to stay clear of prohibited areas.

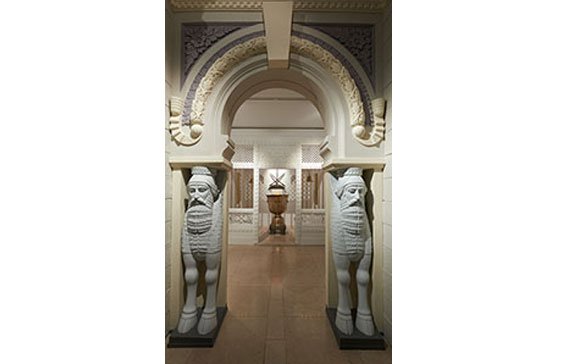

Double Griffin Potome at Persepolis guard the ancient city.

While the walls of the Persepolis are long pillaged, its halls and gates are testimonies of once ancient elegance and complex architecture envied throughout the region. Even the remnants of water tanks and sewage systems still baffle today’s architects. Continued restorations on the site make Persepolis the living, outdoor archeological marvel.

Atop a mountainside, a Zoroastrian tomb sits as a present day spiritual site for believers who still gather here to worship around cleaning fire.

Wall reliefs tell of representatives of nations who came bearing gifts and offerings for the kings. The figure carrying a Griffin Protome vase is said to be an Armenian Tribute bearer in Apadana, Persepolis.

To the left, Asho Faravahar – unborn soul – is the Zoroastrian symbol of the state religion of ancient Persia. With wings and a Persian head – Gopät-Shäh – relief is seen by the eastern entrance and reflects the Empire’s power.

In 330 BC Alexander the Great invaded Persia and sent his army to the city of Persepolis. Through the Persian Gates, within Zagros Mountains, Alexander captured Persepolis and ordered his troops to loot the palaces. During the lootings, a fire broke out and spread throughout the city leaving the entire site ravaged and destroyed. Some historians believe this was Alexander’s revenge over the burning of the Acropolis in Athens during the second Persian invasion of Greece.

The palace walls which were once decorated with ornate tiles and bass reliefs — and statues adorned with gems and golden bracelets and earrings — now stand austere of the riches.

A short drive from Persepolis, the road turns desolate and mountainous – and in a distance, vast mountains reveal spectacular expansive cross shaped carving.

Here at Naghshe Rostam – the cemetery of Persepolis – lay to rest the Achaemenid, Parthian and Sassanid Kings of Persia. The locals refer to the tombs as Persian crosses. Dwarfed by the ancient tombs set high above the ground level, visitors marvel the giant cross shaped carving on the face of the mountains. An opening at the center of the cross reveals small chamber that holds the sacred sarcophagus of kings. In the Zoroastrian tradition, tombs were built high above the ground to be closer to God.

A horizontal beam across each tomb’s facades is said to replicate the entrance to the Persepolis palace. The tombs are identified as those of Darius I, Xerxes 1, Darius II and Darius III. Following the looting of the Persepolis, Alexander’s army also looted these tombs. Continued restorations assure that these ancient tombs are safeguarded from future looting.

Facing the tombs is a square lime-stone, cube shaped structure in ruins. Known as the Kaba ye Zartosht – Zoroasterian Cube – the 5th century BCE structure is an Archaemenid architectural example believed by many as the site of an eternal flame, perhaps in the memory of the kings buried in the facing mountains. Others have argued that the cross ventilation would’ve prevented an eternal flames survival.

Bidding farewell to the ancient kings and poets and centuries old relics of Shiraz, travelers walk or drive under Darvazeh Qur’an – atop which handwritten Qur’ans were once restored to bless travelers passing through. Following reconstructions after multiple earthquakes, the Gate’s Qur’ans were transferred and are today preserved at the city’s Pars Museum – in safe keeping like the rest of Shiraz’s antiquities.