Just what the doc ordered: Gynaec to the stars, RP tells his story

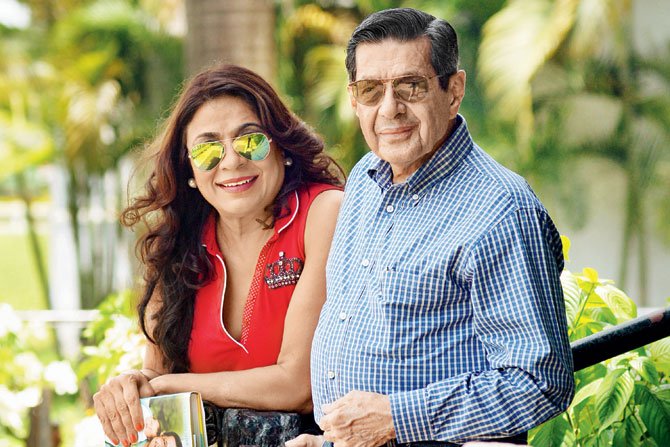

Watching him drive his sedan past some serious afternoon traffic to Gallops restaurant at Mahalaxmi racecourse, and then tuck into kebabs and jalebi cheesecake between sips of techni-coloured fruit mocktail, you wonder if Dr RP Soonawala, aka RP, is actually 86. “You should watch him go for a cotton candy, like a little child,” says food and health writer Rashmi Uday Singh about the object of her admiration and subject of her new book, Lifegiver (published by Harper Collins). The official biography of the Padma awardee gynaecologist and obstetrician. It released this week.

Five years in the making, it has had Singh trail the ridiculously busy octogenarian from one end of the world to the other. “From Mykanos to Jaipur, and everywhere else in between,” she laughs. Although she has authored several titles on food, this was the first time she has attempted a biography. She calls it her most challenging assignment yet, thanks to the research involved and time spent in tracking down RP’s patients. “Most people were more than happy to contribute,” says the author. “We had to spend a lot of time on Google,” says the doctor, smiling, referring to his celebrity clientele. “I quite enjoyed revisiting some of my cases.”

And the bonds are many — right from industrialist wife and philanthropist Parmeshwar Godrej (who is grateful to the doctor for relieving her from the agony of carrying a still born child after all other doctors had refused to operate on her and winning her “unconditional confidence”), to actress Mumtaz, on whom RP performed two procedures he had introduced in 1974 for the first time in the country — laparoscopy and microsurgery — to identify and eliminate a gynaecological niggle and make her fit for pregnancy again. Liquor baron Vijay Mallya flew RP to Los Angeles to deliver his son Sidhartha. Ranbir, Karishma and Kareena Kapoor were all delivered by him too, and in the book, Amitabh Bachchan writes how the doctor is indispensable to his family.

But it is not just the stars or royalty like Rajmata Gayatri Devi. A significant chunk of Dr Soonawala’s patients are from humble backgrounds. “And he treats them with the same kind of compassion, dignity,” says Singh, who while researching for the book, accompanied him to places that have shaped his life, including the house at Grant Road where he was delivered by a mid-wife (as was the practice).

Given that RP began practicing in 1948, the story of his life reads like a chapter in medical history, and that of the city. “When we started practicing, a doctor would feel the pulse of the patient and diagnose —diagnostic procedures and blood groups came later.” From 1956 to the mid-70s, some revolutionary innovations were introduced in medical practice, including sonography which replaced the X-ray. “While technology has got better and pin hole surgeries have become easier thanks to hi-tech cameras, innovations continue to be based on theories that were introduced during the ’60s and ’70s,” says the doctor adding, “I feel happy to be have been part of such a significant era in medical history.”

A personal triumph, says RP, while playing down his contribution, was The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1971. “Those days, women had no say, whether they came from educated backgrounds or otherwise. The mortality rate during abortion was 20 in a 100. There were many cases of women losing their lives to quacks because medically terminated pregnancies were illegal in India,” he says. A steady stream of these women made it to Wadia Hospital in Parel, and Dr Soonawala was at the forefront of a sustained campaign to make it easier for women to choose abortion at an early stage.

Most importantly, he introduced an Intra-Uterine Contraceptive Device that allowed women to plan their pregnancies. The empowering innovation won him the Padma Shri (1991) and the prestigious Von Grafenberg medal from the University of Kiel in 1984.

Medical history apart, the book offers us a glimpse of Bombay-of-the-Parsis, by-the-Parsis. “He took me to the hospital district of Parel, up the wooden stairways, courtyards with old mango trees,” says Singh, who is particularly fond of the community that has been instrumental in building the island city.

“I have always been curious about why so many leading doctors and industrialists are Parsis. I was told it is because of their belief that abundance, rather than abstinence or austerity, is important, and everything they do is to celebrate the abundance of life in its many forms,” she says, recounting how everywhere she went with RP, women rushed out to meet him, with emotional accounts of how he had delivered their children, grand children and praising his quietly assuring presence. “The joke at Wadia Hospital is that if anybody reported to work late, instead of admonishing them, he would ask, ‘Beta, aaj khana khaya?”‘

The discussion veers towards the state of maternity wards in government hospitals, and how here, Mumbai has an edge over other metros. “Most public hospitals in the city have better technology and facilities than government hospitals elsewhere, but I still feel doctors show some reluctance in using them well,” he says. “You see, when we became doctors, medical practice was looked upon as a service. Now it is a business. And the corporate stake-holders are responsible for this change.”

On a lighter note, we talk about his boundless energy. He attributes it to his family with three generations of tireless medical practitioners. His father Dr Phiroze Soonawala practiced back in the 1920s. His son, Darius is an orthopaedic and Zaheer is a general physician. His brother, Dr FP Soonawala is a urologist.

He draws inspiration from his wanderlust. His mother was a traveller with a lust for life, and is responsible for the way he is turned out even in his 80s — his hair has just a dash of grey and he chooses denims and a checked shirt for the interview. The doctor shares a secret. “A curious mind is a young mind,” he says, picking up an orchid bud from the floral arrangement on his table while drawing attention to its shape and colour. “Look at the architecture!” he says.

“You see, the moment you retire and stop using your mind and body, you start ageing,” he says, driving his dessert spoon into the baked Alaska that has just been flambéed.