The Avesta and Zoroastrianism: The Creation, Disappearance and Resurgence of an Ancient Text

Of all the religious texts, the Avesta is perhaps the least familiar. This is unsurprising, since the Avesta was written in a now-dead language, before being lost for almost one thousand years. However, thousands of people still follow the teachings of this ancient text that is thought to have its origins between 1500 and 1000 BC. The Avesta is key not only to understanding Zoroastrianism, but also the origins of younger and more widely followed religions.

What is the Avesta?

The Avesta is the religious text of Zoroastrianism. Zoroastrianism was founded by the prophet Zoroaster at some point between 1500 and 1000 BC. The religion developed from an oral tradition, and its original prayers and hymns were composed in a language which was called Avestan, now long dead.

Thankfully, the Sassanian Empire (224-651 AD) went to great lengths to write the Avesta down. The text is usually divided into 6 sections: Yasna-Gathas, Visperad, Yashts, Vendidad, Minor Texts, and Fragments.

According to Zoroastrian tradition, the original 21 books, called Nasts were revealed by the Zoroastrian god himself, Ahura Mazda. Ahura Mazda is said to have revealed the texts to the prophet Zoroaster, who recited them to King Vishtaspa. The king then had the Nasts inscribed on golden sheets. This work was then memorized, recited at yasna (services), and passed down through word of mouth for generations, until the Sassanians took it upon themselves to record it all.

The original Avesta has expanded over time. Besides Zoroaster’s original teachings, it now includes ecclesiastical laws, commentaries, and customs. New beliefs which came long after Zoroaster have also been added.

Early Development

Zoroastrianism began as a polytheistic religion (a religion with more than one god). Ahura Mazda was seen as the king of the gods, and he was supported by lesser gods and spirits that represented the forces of good. Opposing Ahura Mazda and his retinue was the spirit Angra Mainyu and his forces of darkness. We know that in the early days of Zoroastrianism there was a priesthood that worshipped the gods, but very little other information exists about this early period.

Sometime between 1500 and 1000 BC, one of these priests rose up with new teachings. This priest, Zoroaster, claimed to have received a vision from Ahura Mazda. A being of pure light, Vohu Manah, had visited Zoroaster on the god’s behalf to inform him that Ahura Mazda was the one true god. It was Zoroaster’s responsibility to spread the word.

Unsurprisingly, things did not go well for Zoroaster when he first dropped this bombshell revelation. The priesthood turned against him, and his life was threatened, causing him to flee his home. Zoroaster soon arrived at the court of King Vishtaspa, who had him imprisoned for his heresy. Luckily, Zoroaster managed to win over the king by healing his favorite horse. Impressed by this miracle, King Vishtaspa promptly converted to Zoroaster’s version of Zoroastrianism and commanded his kingdom to follow suit. Zoroaster was no longer seen as a heretic, and his new religion began to spread rapidly.

The new religion revolved solely around Ahura Mazda, the all-good, all-forgiving, all-loving god. All Ahura Mazda wanted was for humans to acknowledge his love through good thoughts, deeds, and words.

According to Zoroaster, his followers had to lead a virtuous life. This was done by honoring Asha (truth) and resisting Druj (lies). It was said that by leading lives of honor, people helped to combat the forces of darkness which were still led by Angra Mainyu. It is during this time that Zoroaster is believed to have composed the Gathas, the earliest section of the Avesta which takes the form of hymns addressed directly to Ahura Mazda. As stated above, legend states that King Vishtaspa had these hymns recorded on golden sheets, but no evidence of these sheets remains.

Development of the Avesta Text

At some point, Zoroastrianism was adopted by the Achaemenid Empire (also known as the First Persian Empire), likely during the reign of Darius I (522–486 BC). Darius’s predecessor and founder of the empire, Cyrus the Great , had referenced Ahura Mazda in inscriptions, but it is likely these inscriptions referred to the old polytheistic version of the god.

Some ancient scholars claimed it was the Achaemenids who first wrote down the Avesta. It was claimed this version was then destroyed during Alexander the Great ’s conquest and destruction of Persepolis in 330 BC. However, most modern historians refute this claim, as there is no trace in the surviving work of an earlier version.

The Achaemenid Empire eventually fell to the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire . During this time, the Greek ruling class largely ignored Zoroastrianism, but allowed the common people to continue their worship of Ahura Mazda. The Seleucid Empire was then succeeded by the Parthian Empire.

The Parthian Empire were much bigger fans of Zoroastrianism, and both the upper and lower classes followed its teachings. Early scholars claimed that another version of the Avesta was written during this period, based upon the version supposedly lost during the burning of Persepolis. However, once again modern scholars can find no evidence of this. It either did not exist or had no effect on the writing of the Sassanian version.

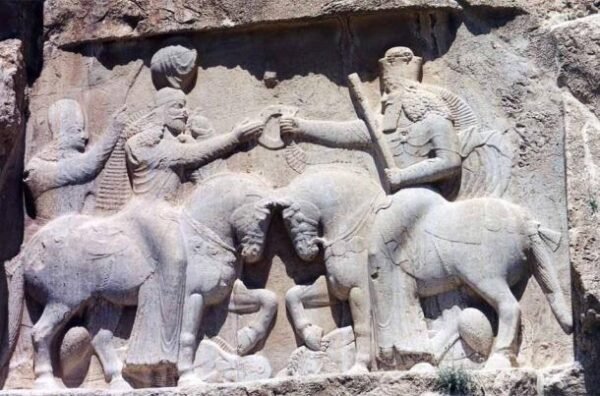

All evidence points to the Sassanians being the first Persian empire to make a written record of the Avesta. It is known that the empire’s founder, Ardashir I , commanded Zoroastrian priests brought to his court to recite the sacred verses, so that they could be written down.

His son, Shapur I , continued the work. It was a long, arduous process that would not be completed until the reign of Shapur II, roughly one hundred years after the process began. Furthermore, nothing was finalized until the reign of Khosrow I, another two hundred years later.

Perhaps it is not surprising the process took so long. The biggest challenge was the creation of a new script that kept the exact sound and sense of the original Avestan words. This process was started under Shapur II, meaning much of the earlier work likely had to be redone.

The Disappearance of the Avesta

The Sassanians spent centuries writing down the Avesta, only for their empire to fall not long after its completion. The Sassanian Empire fell to the Muslim Arabs in 651 AD, and the Arabs soon began suppressing Zoroastrianism in favor of their own religion.

Some followers converted to Islam; some pretended to convert but continued their faith in secret, and many fled the area altogether. Those who fled, the Parsees, settled in India where the religion still has a strong following. If it weren’t for the Parsees, it is likely that Zoroastrianism could have been completely lost to time.

The Muslim invaders burned all the Zoroastrian libraries and destroyed the temples, turning many into mosques. This is known as a dark period for Zoroastrianism, during which countless records and copies of the Avesta were lost.

Thankfully, the Parsees took the Avesta with them to India, so not all was lost. Outside of India Zoroastrianism was all but forgotten, besides the occasional commentary by Greek, Muslim, and Christian writers. Due to the destruction of the Zoroastrian temples and libraries, these commentators had little to work with. As far as anyone in the region knew, the Avesta had been completely lost during the 7th century AD.

The Return of the Avesta

Amazingly, it wasn’t until 1723 AD that Europeans realized the Avesta had survived. A merchant traveling through India found a copy and brought part of an Avestan script back to Britain.

The manuscript sat in the Bodleian Library at Oxford University until 1755, when a young French scholar named Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron happened upon it. He would later embark for India, returning home with over 180 Avestan manuscripts in 1762. Upon arriving home, he dedicated himself to translating them. To this day, all Avestan scholarship in the West originates from Anqueutil-Dupperron’s work.

The Contents of the Avesta

The Avesta is made up of several different sections, but the most important is the Gathas. These were personal songs of praise directed to Ahura Mazda. They don’t contain any instructions on how a Zoroastrian should live their life. Instead, it is believed that Zoroaster must have simply told his followers in simple terms through direct speech how they should act. This lack of clear instruction in the Gathas meant that additional books like the Vendidad, Visperad, and minor texts became necessary for Zoroastrians to specify suggestions for daily life.

The Vendidad

The Vendidad is perhaps the closest Zoroastrianism gets to a ‘traditional’ religious text like the Bible. Despite this, its importance to the religion is disputed by many modern-day Zoroastrians. Some Zoroastrians find it to be little more than extra information, while others see it as valid.

The Vendidad is made up of 22 sections called Fargards that act as a kind of instruction manual for Zoroastrians to follow. Some of the sections consist of myths and religious tales; other Fargards are made up of hymns and rituals, and some include observances.

The first three Fargards contained Zoroastrianism’s most ancient tales, some of which date back to the 8th century BC. These include the Zoroastrianism creation myth and the tale of King Yama and the salvation of the earth. The tale of King Yama is of particular interest to religious historians, as it can be seen as a potential inspiration for the biblical tale of Noah and the ark.

Most useful for Zoroastrians, the Vendidad also included a range of instructions. Some of these referred to good personal hygiene, while others detailed acceptable and unacceptable social customs, the importance of charity, and caring for animals.

Besides the more mundane day-to-day instructions, the Vendidad also offers more spiritual instruction. For example, there are instructions on how to deal with demons and how to use dogs to ward off evil spirits after death.

The Avesta’s Minor Texts

The minor texts are a collection of prayers used to ask different deities for help. Since later Zoroastrianism is monotheistic, these minor deities all represented aspects of Ahura Mazda. Depending on the problem one was facing, certain deities like Anahita or Mithra were more helpful than others.

The minor texts include the Siroza, Nyayeshes, Gahs, and the Afrinagans. Each text described asking for a different type of help from a different deity. The Siroza was used to ask for help in a time of need, while the Afrinagans was used for blessing the dead and for the seasons. The Nyayeshes are used to pray to Zoroastrianism’s four divine elements: fire, water, sun, and moon. Finally, the Gahs are made up of invocations and prayers to the five deities of the day.

The Avesta Fragments

Due to Zoroastrianism’s messy history and the fact that so many texts were destroyed, there are also fragments left over. These are incomplete texts or texts that do not mesh with other parts of the Avesta. Although these might sound superfluous, they actually hold some incredibly important information on the deities that came before Ahura Mazda, as well as theological events like the apocalypse.

These fragments are of great interest to religious historians who have tied parts of the fragments to later monotheistic religions, for example, how the fragments deal with life after death, heaven and hell are startlingly similar to later Christian concepts.

Conclusion

It is a shame that so many people are unfamiliar with the Avesta, as well as Zoroastrianism as a whole. Despite the fact the Avesta all but disappeared for centuries, it played an unimaginably important role in shaping the world and its faiths as we know it today.

The Avesta’s guiding light informed the actions of the greatest empires in the ancient east. Many important facets of modern religions can be traced directly back to the Avesta. A monotheistic religion featuring an all-powerful, all-loving, and all-forgiving creator sounds more than a little familiar. Likewise, Zoroastrianism is the first monotheistic religion to deal with the themes of a messiah, heaven and hell, an apocalypse, and judgment after death. These are all concepts that later religions like Christianity, Judaism, and Islam would develop further.

However, it is important to remember that Zoroastrianism isn’t an ancient dead religion whose only role was to inform the major religions of today. It is still an active religion in its own right, with many people still practicing it. It should be respected as a modern religion that encourages love, respect, and understanding in a world that is so often lacking all three.

Top image: Zoroastrian Fire temple at Baku, Azerbaijan adapted practiced according to the Avesta and other Zoroastrian scriptures. Source: Konstantin / Adobe Stock

By Robbie Mitchell

Source: Click Here