Why did JRD Tata’s Air India have 8,000 artistic treasures? Raza, Husain, ashtrays by Dali

The publicity hoardings Tata mounted for Air India said: “We do business in 3 languages – English, English, English.”

In mid-2012, out of the blue as it was, reports appeared saying that Air India was preparing to sell its art collection, one of the most valuable in the world. This was when the national carrier, mishandled by national leaders for long, had run up a debt of ₹43,777 crore and accumulated losses (in the previous five years) of ₹27,700 crore. Fortunately, the family jewels were not sold at that time.

Six years later, in mid-2018, again unexpectedly, came an announcement that the government was open to the idea of putting up the Air India collection as a permanent art exhibition under the custody of the National Gallery of Modern Art. This followed a proposal by an Air India chairman to set up a museum at the airline’s own headquarters in Mumbai’s Nariman Point. A tender was floated, estimating the museum’s cost at ₹3.5 crore. It came to naught when the government decided in mid-2017 to privatise the national carrier.

It is another matter that there were no takers for the privatisation idea. What was at stake was a unique collection of about 8,000 artistic treasures. Nearly 4,000 were paintings by masters of Indian art, from M.F. Husain and K.H. Ara to S.H. Raza and V.S. Gaitonde. There were sculptures and woodwork, antique clocks and memorabilia, some of them going back to the 9th century. There were ash trays designed by Salvador Dali, which were meant to be gifted to first class passengers. Air India’s menu cards were famous for the paintings reproduced on them. These too were faithfully collected and listed among the treasures.

What was an airline doing with paintings and sculptures? That is a question that will take us to the magnificence that was Air India in its early days and the shame it became later. It was a proud national flag carrier in every sense of the term until it turned into a national embarrassment following nationalisation. Across the board, nationalisation meant the replacement of visionaries by shortsighted politicians and bureaucrats. It denuded the country of its aesthetics, its joie de vivre, its buoyant liberalism, converting even the cheerful cosmopolitanism of Bombay into the arbitrary micro-culturalism of Mumbai. Air India withered in that climate. But that did not affect either the reputation or the leadership position of ‘the Tatas’, a name that had come to represent all that was good and noble.

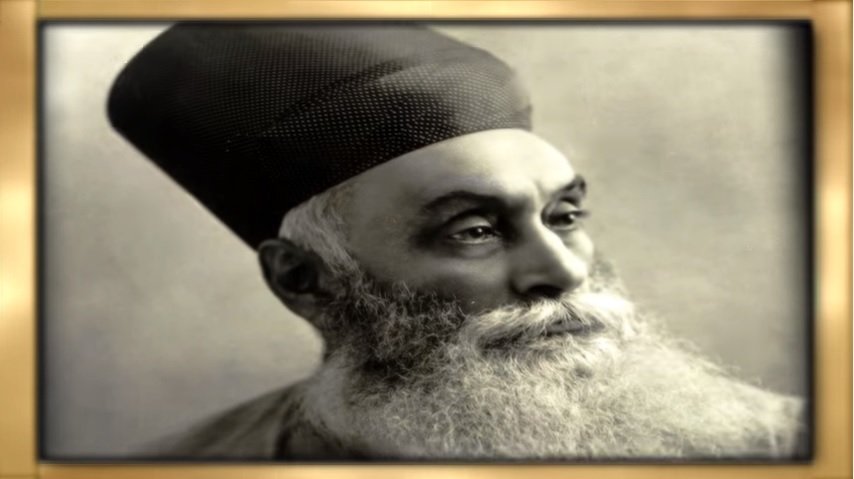

Behind that reputation were the insights that guided the conglomerate’s founding father, Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata. When he set out on his mission in the mid-19th century, Jamsetji laid down two principles—keep social responsibilities in mind while pursuing business success, and uphold nationalism in the era of colonialism. The dreams he had developed could not all be realised during his lifetime. But the standards he set helped Tata enterprises develop a character and a social standing that were unequalled. That standing won fresh laurels under J.R.D. Tata whose principle ‘Live life a little dangerously’ gave his persona a touch of glamour.

J.R.D. took Jamsetji’s mission to new horizons by building on the humanism that had guided the founder. It was the Tata approach to life and business that made Air India different from other airlines. Its contributions to the prestige of India were incomparable, significant, and visible. To J.R.D., the founder, Air India was not just an airline. It was a national symbol consciously developed as such when India was beginning to emerge on the world scene.

Tata Airlines, founded in 1932, changed into Air India on the eve of independence when there were few airlines in the world and fewer flying across continents. Going abroad was an exceptional experience for ordinary Indians until the 1960s. When Air India’s first flight to London took off from Bombay in June 1948, it had to stop at Cairo and Geneva en route. In a universe still waiting to be opened up, Air India set out to project to the world the wonder that was India. It did so with such dedication and imagination that the world marvelled at the colours of India, the warmth of its hospitality, the variety of its cuisine, and the richness of its art.

The inspiration for all that came from one man. The standards J.R.D. set were high and he would personally check things out from time to time—the cleanliness of the pantry, the freshness of the window curtains, the spotlessness of the toilets. If he wanted improvement somewhere, he would send a polite note to the managers. If Air India’s greatest asset in its formative years was J.R.D.’s vision, J.R.D.’s winning asset was the creative genius of a staffer named S.K. Kooka. He carried a humdrum job title, commercial director, but it was Bobby Kooka who made Air India a household name, and a beloved one at that.

He invented the Maharaja as the airline’s mascot, named the flights the Magic Carpet services, and introduced an inflight booklet with the title ‘Foolishy Yours’. The publicity hoardings he put up always made an impact, although one that said ‘We do business in three languages; English, English and English’ rubbed some patriots the wrong way. Kooka not only shared J.R.D. Tata’s ambitions for Air India; he enlarged on them as he translated ideas into action.

He wanted Air India offices, especially those abroad, to project India’s cultural splendour. Art became a tool for him. Such was his attention to detail that he put emphasis on the exterior walls of Air India’s offices in Europe’s premier cities. Colourful murals on Indian themes by Indian artists were mounted on the walls making them points of attraction for the locals passing by. The world got a close-up view of India, a colourful one that caused excitement. To realise the dreams he had on the art front, Kooka enlisted the services of Jal Cowasji, officially Air India’s publicity chief, but in reality a connoisseur of modern art respected by aficionados for his knowledge and for the high standards he set for himself. Cowasji was allowed to do what he thought fit. He could buy and commission art.

This was at a time when buying art was not common in India, and buying it as an investment was unknown. It was also a time when there were no stellar names in the field. Husain and Ara and B. Prabha and other stalwarts of the Bombay Progressive Group were around, struggling to get some attention and considering themselves lucky if someone bought a painting for three- or four-hundred rupees. Often, Air India paid artists in the form of free tickets. That was the milieu in which Jal Cowasji was able to put together an impressive collection of antiques, jewellery, studio photography, as well as paintings.

The general public got a taste of the treasure in 2008 when Air India brought out a coffee table book (Mapin Publishing) with 201 colour illustrations and analyses by four experts. Interestingly, Air India was not alone in collecting and patronising art in those halcyon days. An unlikely rival was the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR).

Source: Click Here