Ardeshir Irani: The School Teacher Who Brought Sound to Indian Cinema

Besides making Alam Ara in 1931, Ardeshir Irani also gave India its first indigenously made colour film and first-ever talkie.

After Prithviraj Kapoor made his pact with god at the Gateway of India, he asked the Victoriawalla to take him to a hotel. He did not know a soul in this city, nor did he have a single address. The driver left him at Kashmir Hotel, opposite Metro cinema, where he got a room for five rupees a night. The next morning, he asked the manager of the hotel where the nearest film studio was. Aware by now that his seventy-five rupees would not last very long, he walked to Imperial Studios on Kennedy Bridge, near the Royal Opera House.

The studio belonged to the legendary Ardeshir Irani, who made India’s first talkie Alam Ara.

As Madhu Jain detailed in her book Kapoors: The First Family of Indian Cinema (2005), Kapoor’s iconic 70-year career, “from the silent era to technicolour and 70 mm”, began at the gates of this very studio. It wasn’t just him – icons like Mahboob Khan and Sulochana too shaped their career trajectories under Ardeshir Irani’s guidance.

Irani is widely regarded as the ‘father of Indian talkies’, and has several firsts to his name, the most famous being India’s first talkie Alam Ara in 1931.

In 1933, he made Lor Girl, the first-ever sound film to be made in Persian. Set in post-World War I Iran, it features a couple that escapes to India to find solace from the lawlessness that had taken over their homeland. It was the first time an Iranian movie had featured a woman in the lead.

Irani also went on to direct Kisan Kanya (1937), India’s first indigenously made colour movie, based on a novel by Sadat Hasan Manto focussing on the poor plight of farmers.

It is said that Ardeshir had always been a dreamer – a man looking to find his place amid something bigger, something better. Throughout his career, not only would he achieve his dream but also shape Indian cinema as we know it today, almost a century later.

Venturing into the unknown

Born on 5 December 1886, Khan Bahadur Ardeshir Irani was the son of Iranian immigrants who had arrived in India towards the end of the 19th century to escape religious persecution. He began his professional career as a teacher, and briefly, a kerosene inspector.

Hoping to achieve bigger goals, he soon shifted to following in his father’s footsteps, taking up a business of selling musical instruments.

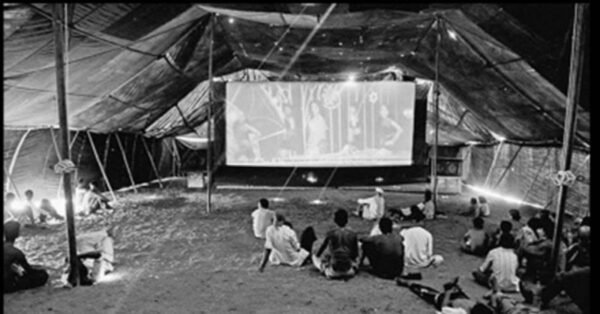

His dreams would find stronger footing when he won a lottery of Rs 14,000, a big sum in those times. This gave him the finances to step foot in the film industry, and he began as a small-time film distributor, putting up movies in ‘tent cinemas’ with projectors. He did so with Abdulally Esoofally, an early film entrepreneur with who he would go on to have a long working relationship.

“This started a cinema-viewing culture,” said researcher and writer Sharon Irani. “Tent cinemas were set up in maidans, and then inside old theatre houses…much before cinema halls and multiplexes came into existence. Before the ‘tambu’ talkies, ‘lavani’ and ‘tamasha’ had been sources of entertainment…but tent shows changed the way you entertained in those times.”

In 1905, Irani became the Indian representative of Universal Studios, showcasing Hollywood movies to the average Indian audience. He soon began running the Alexander Theatre with Esoofally, and it was here that he learned the ropes of filmmaking and producing. This, coupled with his great admiration for Dadasaheb Phalke, pushed him to foray into the field for the first time in 1920 when he produced Nala Dayamanti.

The same year, he would establish his Star Films Limited, a studio that launched the career of Fatma Begum, Indian cinema’s first woman director. He later set up Majestic Films and Royal Art Studios. The latter became famous for romantic movies set amid fantasy lands — like Naharsingh Dakoo (1925), set in a fictitious kingdom and following the journey of a kind-hearted bandit who exposes the treacherous doings of the minister and his wife.

In 1926, he set up Imperial Films Studio, where he made over 60 films. It was this studio that forever changed the landscape of Indian cinema with the release of Alam Ara.

Of the inspiration behind the movie, Ardeshir told film historian BD Garga, “About a year before I set upon producing Alam Ara, I had seen Universal Pictures’ Show Boat (1929), a 40% talkie, at Excelsior. This gave me an idea of making an Indian talkie film. But we had no experience and no precedents to follow. Anyhow, we decided to go ahead.”

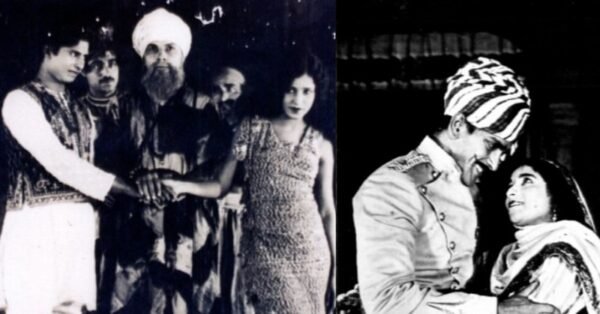

Alam Ara set the precedent for the kind of movies Indian cinema would go on to make – complete with dancing and singing (seven times, to be precise). “With the release of Alam Ara, Indian cinema proved two things — films could now be made in regional languages that local viewers could understand; and that songs and music were integral parts of the entire form and structure of the Indian film,” wrote scholar Shoma Chatterjee.

It wasn’t such Indian cinema that benefitted from his work. After Alam Ara, he released Lor Girl, and his presence in the Iranian film industry found even more importance. He produced works like the 1934 romance movie Shirin & Farhad and even found himself in front of the camera as an actor in the biographical drama Firdowsi (1934). He made films in Hindi, Gujarati and Marathi to Telugu, Burmese, Farsi and English.

He made movies up until 1945, with some sources saying that the number in his repository touched a whopping 200 films. After the Second World War began, Irani thought it was unsuitable to continue making movies in such tumultuous times, and suspend film production. His last film, Pujari, was released in 1945, and he died on 14 October 1969, at the age of 82.

‘Father of Indian talkies’

Alam Ara’s success had dealt a heavy blow to the silent film era. Before sound was introduced in movies, actors could mask their poor diction, but the advent of talkies changed the game completely, especially for Anglo-Indian actors, who had somewhat dominated the industry up until that point.

Moreover, introducing sound in cinemas meant that the industry had to reimagine the very idea of filmmaking – existing systems of production and exhibition could no longer suffice.

“Producers, the country over, were either transforming their old studios or building anew, in a raging tearing manner, to house the new order of things,” observed the Indian Cinematograph Book in 1938. Silent projectors were replaced with sound equipment, and theatres were made soundproof. ‘Hindustani’, an amalgamation of Hindi and Urdu, subsequently became a popular language in Indian cinema. And finally, Indian films found precedence over American and British movies, a feat filmmakers had been trying to attain for many years prior.

Irani also unknowingly ushered in a new way of making movies with artificial lighting. At the time, films were shot in natural light, which left the cast and crew at the mercy of unpredictable weather. His decision to shoot indoors under heavy light would eventually make way for shooting indoors, a practice that proved to be economical as well as convenient.

Today, Indian cinema produces around 1,800 movies a year and is nothing short of a global enterprise. It’s the lavishness and the extravagance of it all – majestic locations, fantastical plotlines, songs, elaborate costumes, and the like – that attracts an audience from over 90 countries.

It was Irani’s ambition that set the stage, so to speak, for the cinema we know and love today.

Source: Click Here