Sam Manekshaw through the eyes of his family and friends

The year was 1969, the place was Calcutta, and the occasion was the marriage of actor Sharmila Tagore and Mansoor Ali Khan, Indian cricket captain and the nawab of Pataudi. As the wedding reception at the officer’s club in Fort William continued late into the evening, a huge mob started gathering outside. The high-profile interfaith marriage had led to communal polarisation in Bengal, and it soon became a major challenge to ensure safe passage for the couple. As tension continued to mount, a 1937 Austin Sheerline car arrived to pick up the newlyweds. It was sent by Sam Manekshaw, the general officer commanding-in-chief of the Army’s Eastern Command. In Calcutta those days, the Sheerline was as famous as Manekshaw and hence, enjoyed easy passage throughout the city. It perhaps saved the couple as they made their way out of the club. In his eagerness to help, Manekshaw prevented what could have been a massive tragedy that day. The fact that he loved Bollywood movies of the 1950s and 60s, too, helped.

The chevron-moustached Sam Hormusji Framji Jamshedji Manekshaw, who was born on April 3, 1914, in Amritsar, was the face of India’s victory in the 1971 war with Pakistan. He was appointed Army chief in July 1969, and in January 1973, the month of his retirement, he was made field marshal, the first Indian to be bestowed with the honour. Nearly five decades later, his appeal as a soldier and a Parsi bawa—the two often indistinguishable—continues to transcend his military exploits. His cheeky humour, distinctive panache for grooming and his innumerable quirks—a strong dislike for umbrellas and mikes, a penchant for Barbie dolls and joy in hoarding preserves and canned foods—continue to be the subject of living room conversations.

Manekshaw’s refrigerator was a treasure trove of exotic delicacies, from Russian caviar to canned fish, many of which would remain inside the fridge long after they had crossed their expiry dates. “Yet, he would not let anyone throw them out,” said Sule Bahadur, Manekshaw’s Gorkha batman and cook for more than 40 years. In the Manekshaw household, there were two kitchens—one that belonged to Bahadur and the other run by Manekshaw. “Sam had a really big freezer. Those days people were not comfortable keeping food in the freezer for long, but he would proudly brag about all the stuff he had in there, especially the dhansak (a traditional Parsi delicacy made by cooking mutton or goat meat with a mixture of lentils and vegetables) which was always at least a year old. And then he would taste a spoonful and animatedly pat himself on the back,” Bahadur told THE WEEK from Nepal, where he is settled after retirement. “He loved cooking, especially doing the barbecues. He had an elaborate collection of all the latest cookware.”

Manekshaw’s barbecue exploits would come in handy while hosting dinners. Those who have experienced his gracious hospitality recall him as being an excellent host. “He would never let waiters or orderlies serve drinks to his guests. He would do it himself. During barbecue evenings at home, he would be turning the skewers himself and would expect his guests, too, to do the same. The food was never pre-cooked and all the fresh salads would be from his own garden,” said Bahadur.

Manekshaw, his wife, Silloo, and their two daughters, Sherry and Maja, lived together throughout the field marshal’s multiple postings, notwithstanding the challenges like moving schools that came with it. “He was a devoted family man. We were his wealth,” said his elder daughter, Sherry Batliwala. Everywhere the family went, the Manekshaws nurtured a garden, four dogs, a flock of hens, a buffalo, two “very special” Jersey cows, and everlasting relationships.

“We had so much homegrown fruits and vegetables, milk and eggs that we would supply to the entire neighbourhood. It was totally my father’s interest. He would wake up at six, put on his shorts and tee and head out to the garden for two hours every day,” said Sherry. “Nothing about him ever annoyed me. I adored him so much. I never eat curd, because my father never had it.”

On her wedding day, when the bride and the groom came to him for his blessings after the ceremonies got over, he told them, “Bas ab sab shaadi vaadi ho gaya, ab tum ghar aao (Now that the wedding is over, you come back home).” Sherry said what went on at the Manekshaw household would probably not be understood by most people. “We were a very politically incorrect family,” she said, bursting into laughter. Both daughters, however, remember their childhood as being “magical, travel-rich and free of unsolicited advice”.

Manekshaw’s younger daughter, Maja Daruwala, said there was no fight for control and no concept of gender-defined roles to adhere to in her family. “Although mom was at home, she would not be expected to cook,” said Maja, a lawyer and human rights advocate.

She spoke about the time in 1957 when Manekshaw was sent to the Imperial Defence College, London, to attend a year-long higher command course. “He would do all the cooking for the family without ever once making it look like a chore,” she said. “At the time, I was a fussy eater. Yet, he would cook for us all. He was superb at making chhole bhature, kheema pao, makki di roti, sarson ka saag and bhuna chana soup. He never imposed his military discipline on us. During holidays, we would sleep till 10am and he would leave us alone, although he loved to have breakfast with us. Even when it came to his hobbies such as fishing and photography—he had all the state-of-the-art equipment—he never forced them upon us. We were, however, always turned into reluctant scapegoats for his experiments.”

Ready to serve: Manekshaw as cadet at the Indian Military Academy | Parzor Foundation Archives

If the girls brought their boyfriends home, they did not want to be with him because “he would make mincemeat out of them with his piquant humour”.

There was a lot of teasing going around in the house, mostly aimed at Manekshaw by the three women, especially when it came to aesthetics. Silloo, an alumna of Mumbai’s Sir J.J. School of Art, was an exceptionally talented artist and painter. Her paintings adorned the walls of every house the family stayed in. Their own home, Stavka, was a majestic bungalow with terrace gardens nestled in picturesque Coonoor in Tamil Nadu’s Nilgiris ranges. Silloo purchased the plot way back in 1963 for a princely sum of Rs18,500. She conceptualised and designed the bungalow from start to finish. It served as their retirement haven.

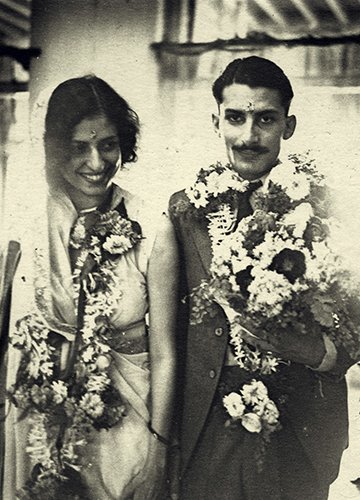

Manekshaw was a flamboyant young captain when he married Silloo Bode in 1939. He “swept her off her feet” at a dinner party in Lahore; she was visiting her sister and brother-in-law who was a doctor in the British Indian army. Manekshaw often said Silloo was both his ardent supporter and his harshest critic. She was the wind beneath his wings, and she was also the one who kept him grounded. “He was quite aware that he was extremely charming and good looking. But mother would put him straight,” said Sherry. “She would remind him that he came from a middle-class family in Amritsar. ‘They would venerate you today, but tomorrow when you are no longer the field marshal or the director of a company, you would be a nobody,’ she would warn him. I think that kept him a little focused also.”

Brigadier Behram Panthaki (retd), who served as ADC (aide-de-camp) to Manekshaw from 1965 to 1971, said Silloo was quite unassuming despite being the wife of a senior officer. The brigadier and his wife, Zenobia, who have published the book Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw: The Man and His Times, spoke to THE WEEK over a Zoom call from the US. “She would not be bothered about protocol,” he said. Panthaki shared an anecdote from a Republic Day function, when they were at the Rashtrapati Bhavan. Around 25 VVIPs were invited for tea. “While we were walking to the VVIP enclosure, the field marshal was ahead and Mrs Manekshaw was a few steps behind him. A security officer stopped her, saying that her name was not on the guest list. The field marshal heard that and told the officer, ‘Yeh toh meri biwi hai. Aapko maloom nahin hai ki iska gussa bahut kharab hai? Isko mat roko aur aane do mere saath (She is my wife. Don’t you know how bad her temper is? Don’t stop her. Let her come with me).’”

When Manekshaw rose to higher ranks, Silloo never demanded special privileges. Both of them remained grounded and humble. For instance, although they were entitled to a house call when unwell, they would go to the armed forces clinic, stand in the queue, collect their tokens and see the doctor.

Shernaz Cama, director of the UNESCO Parzor Project which aims to preserve Zoroastrian culture, first met the Manekshaws as a bright-eyed 11-year-old in late 1971 in Calcutta. Her father, Adi Meherji Sethna, who went on to become vice chief of Army staff, was then brigadier general staff at the Eastern Command headquarters.

Later on, she got many opportunities to spend time with them. As a student in Wellington, near Coonoor, she would often accompany Manekshaw on flights from Coimbatore to Delhi, where her parents were posted. “I will never forget those flights,” she said. “He would always be at his cheerful best and dole out generous compliments to air hostesses. I used to tease him, saying he was flirting with them, despite being an old man. And he would promptly say, ‘These girls are working so hard. I make them smile. They know I don’t mean it and I know I don’t mean it, but it makes them happy.’”

Cama has fond memories of Silloo as well. “She hailed from a well-to-do family and I remember her giving my mother a piece of advice. She told her, ‘You are a general’s wife (Sethna retired as lieutenant general), but remember, before he retires, practise how to kick shut the car door and carry your packages out at the same time. The day you retire, come back to earth,’” said Cama. “She was saying it from a bitter personal experience after she asked an officer to post a letter on Sam’s behalf. He did not seem to have recognised her as Sam had retired from active duty by that time. The officer was shocked that somebody was asking him to run an errand.” Those days, a general’s wife never carried her packages herself because there would be enough staff around to help. Yet, Silloo was always unflappable. Even during the unsettling time of the infamous court of inquiry against Manekshaw for his alleged “anti-national activities”, ordered by defence minister V.K. Krishna Menon in early 1962, she continued with life as if nothing were amiss.

Even as she enjoyed a game of cards or mahjong with Army wives, Silloo’s primary concern was the welfare of people around her and her most significant contribution to Coonoor was the setting up of a clinic for the poor, a free and charitable establishment which runs to this day. “She would direct plays at the staff college and sell her paintings to raise money. More than Sam, Silloo was the face of the Manekshaws in Coonoor because she used his reputation to collect money from across India for the welfare of the place,” said Raj Shinde, who helped Silloo run the clinic. Her husband, Colonel Dr Anil Shinde (retd), served as Manekshaw’s physician for over two decades.

Sherry recalled her father’s comment at her mother’s funeral, for which not just members of the Army family, but also shopkeepers, villagers and almost the whole of Coonoor was present. “When I die, all these people are certainly not going to turn out for me,” he said.

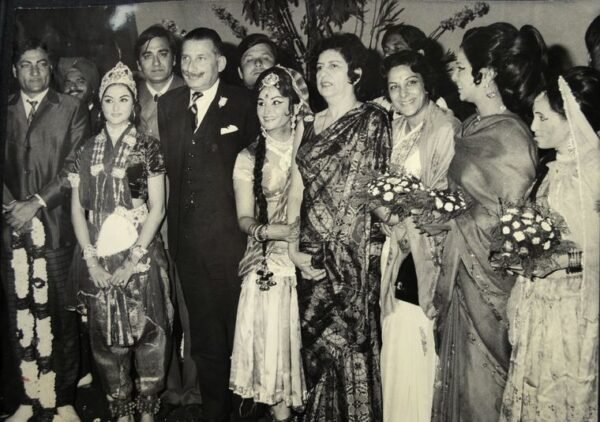

Shining stars—Manekshaw and his wife, Silloo, at a Bollywood party | Parzor Foundation Archives

Silloo’s room at Stavka was done tastefully in pink and blue, but Manekshaw had the biggest wardrobe and dressing room that stretched from wall to wall and ceiling to floor. “We used to laugh and say we all know who was the vain one in the house. While Silloo wouldn’t give a damn about what she wore, Sam would be immaculately groomed even for a night walk,” said Raj.

Panthaki agreed with Raj’s view. “When I joined him as ADC in Calcutta, it became a problem for me to attend social functions with him, because I only had a uniform, which would come handy for military functions,” he said. “He would wear flannels and a blazer for morning functions and a suit for the evenings. And he wanted me to do exactly the same. I told him that with a monthly allowance for 0300, I could not afford to keep pace with him. A week later, he took me to Park Street, got me material for my tweeds and even kept a tailor handy to take my measurements.”

Manekshaw was Sam to everyone, even to his two daughters and his three grandchildren—Sherry’s daughter, Brandy, and Maja’s sons, Jehan and Raoul-Sam. To his grandchildren, Manekshaw was the man who never doled out career advice, who would repeat his jokes 500 times over, who expected them to know the name of each rare rose breed in his garden, who was a hoarder with cabinets full of unopened old wines and vodka, and who would drive down to Coimbatore airport in his Sunbeam Rapier to receive them whenever they came visiting. Jehan now runs a drama school in Mumbai, while Raoul-Sam works for a tech firm in the US. Brandy lives in Goa and works in the hospitality sector.

Manekshaw and Silloo celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary in 1999. She died two years later. She was 90, and was suffering from lung cancer. After Silloo’s death, Manekshaw got terribly lonely. “So one day, my wife and I took him out for lunch at the Ootacamund Club,” said Shinde. “There were about 100 people there, and the poor man could not eat as everybody came along with napkins and menu cards and books, requesting him for an autograph. He must have been 88 at the time. Yet, he was mobbed.” Manekshaw died on June 27, 2008, and was laid to rest in a Parsi cemetery in Ooty, next to where Silloo sleeps.

When Manekshaw turned 90, Jehan and a young filmmaker, Jessica Gupta, convinced him to talk about his life for a documentary film as part of the UNESCO Parzor Project. In the film, Jehan could be seen asking Manekshaw about his greatest achievement in life. “From the ranks of second lieutenant to field marshal, I have never punished a man,” replied Manekshaw. “I would sign court martial proceedings when the verdict was not guilty. But if it said guilty, I would take the file home and look at it and then would say no. They would question my decision, and I would tell them that sitting happily in Delhi they had no idea what those chaps on the ground are going through.”

When Manekshaw turned 90, Jehan and a young filmmaker, Jessica Gupta, convinced him to talk about his life for a documentary film as part of the UNESCO Parzor Project. In the film, Jehan could be seen asking Manekshaw about his greatest achievement in life. “From the ranks of second lieutenant to field marshal, I have never punished a man,” replied Manekshaw. “I would sign court martial proceedings when the verdict was not guilty. But if it said guilty, I would take the file home and look at it and then would say no. They would question my decision, and I would tell them that sitting happily in Delhi they had no idea what those chaps on the ground are going through.”

Source: Click Here