The pioneering lawyer who fought for women’s suffrage in India

Amid the pandemic gloom, it is easy to forget that the year 2020 marks an important anniversary for women’s rights.

In the US, it has been 100 years since women cast their votes for the first time. A century ago in the United Kingdom, the first female law students were admitted to the Inns of Court.

At Lincoln’s Inn in London, one of those students, Mithan Lam, was an Indian. In 1924, she became the first woman to be allowed to practise law in the Bombay High Court, shattering one of the thickest glass ceilings for professional women in the country.

But Lam’s influence extended well beyond the bar: she left an indelible stamp on the female suffragist movement and the struggle for gender equality in India.

Lam was born in 1898 into a wealthy and progressive Parsi family. While on a holiday in Kashmir in 1911, she and her mother, Herabai Tata, had a chance meeting with Sophia Duleep Singh, an ardent feminist and suffragist in Britain.

Intrigued by a colourful badge Singh wore proclaiming “Votes for Women,” Lam and Tata were quickly drawn into the cause of Indian female suffrage.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESSuffrage was a contentious issue amongst nationalists in colonial India: should women’s enfranchisement be prioritised over Indian independence?

Lam saw no contradiction between the two demands, branding men’s reservations against women’s voting rights as “soap-bubble material”. “Men say ‘Home Rule is our birthright’,” Tata stated in 1918, echoing a famous nationalist slogan. “We say the right to vote is our birthright, and we want it.”

In the autumn of 1919, women’s groups in Bombay decided to send representatives to London when the British Parliament was considering female suffrage in a package of political reforms for India – also known as the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms.

Lam, 21, and her mother were the natural choice, given their determined activism. Since they were given only four days notice before setting sail to England, they composed their parliamentary evidence on the boat.

Tata and Lam’s evidence highlighted the impossibility of meaningful political reform if half of India was excluded on the grounds of sex. “Attempt to reform without the co-operation of women,” they argued, “and you are simply raising a paper fabric on foundations of sand.”

While unsuccessful in their immediate objective, their evidence might have spurred the British Parliament to leave the decision about female suffrage to the discretion of the Indian provinces. In 1921, both Bombay and Madras presidencies granted limited women’s franchise.

Mother and daughter also captivated the British public with their passionate advocacy of Indian women’s issues, earning the support of Ramsay MacDonald, the future British prime minister, and the feminist icon Millicent Fawcett.

Lam’s suffragist activities eventually led her into the world of law. While in London, she decided to pursue a legal education and a master’s degree in economics from LSE. In 1923, she had the distinction of being the first ever woman called to the Bar from Lincoln’s Inn as well as the first Indian woman called to the Bar in Britain.

The newly minted lawyer sailed back to India in December 1923. It was a fortuitous time to return because that year, the Indian government removed disqualifications for women to practise law.

Lam found herself in a daunting situation as the sole female lawyer in the male bastion of the Bombay High Court. “I felt like a new animal at the zoo, with folks peeping through doorways,” she recalled. “As soon as my shadow crossed from the library to the common room, there would be an uncomfortable silence, making me feel even more self-conscious.”

Misogyny, ironically, might have played a role in landing Lam her first court appearance.

According to a former Supreme Court judge, Lam was approached by a solicitor whose client had a watertight case. “He has such a good case that he cannot lose,” the solicitor claimed. “But he wants to inflict upon the opponent the humiliation of being defeated by a woman.”

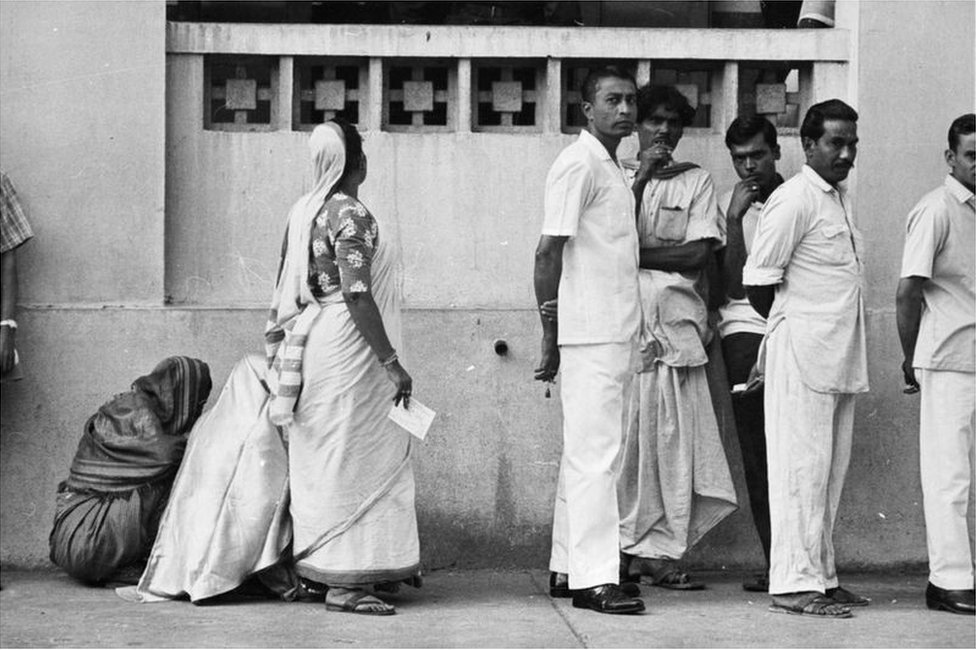

IMAGE COPYRIGHTKEYSTONE

IMAGE COPYRIGHTKEYSTONEWithin a few years, however, Lam built up a solid legal reputation. She appeared in an eclectic mix of cases in court, ranging from prosecuting currency counterfeiters to defending the validity of a Jewish betrothal.

Outside of the courtroom, she helped shape gender-sensitive legislation for marriage and inheritance and became a prolific advocate of women’s and children’s rights.

But she matched this legal activism with on-the-ground social work, shuttling between Bombay’s elite drawing rooms and its teeming slums. Lam brought slum dwellers improved infrastructure and health facilities, helped resettle Partition refugees and led numerous social welfare activities of the All India Women’s Conference.

In 1947, the year of Indian independence, Lam added another first to her credit.

She was appointed as the sheriff of Bombay, the first female sheriff in India. Years later, when she travelled the world as a representative of Indian women, this caused occasional puzzlement. San Francisco’s sheriff took her for a visit to the city’s prisons and gave her a police baton, not knowing that a sheriff in India occupied a largely ceremonial position. “They were rather intrigued about the fact that a woman could be a sheriff, for in the US sheriffs are real police officers and have to be quick with the gun,” she recalled.

By the time she died in 1981, Lam had mentored generations of feminists, hopeful that the growing number of women in law would stimulate political and social reform in India.

Her work – as well as the work of hundreds of other relatively unknown female pioneers – has paved the way for law becoming an increasingly popular career choice for Indian women today.

But according to a recent study, while certain leading law firms exhibit remarkable gender parity, the Indian legal profession continues to be overwhelmingly male-dominated.

Exactly a century ago, Lam rallied against gender-based exclusion with a poignant question: “How can the women be declared unfit without even being given a trial?”

Such words may hold a special resonance today with female trailblazers working their way up in traditionally patriarchal bastions, whether inside or outside the courtroom.

Parinaz Madan is a lawyer and Dinyar Patel is a historian.