Zoroastrians make a comeback in northern Iraq, but still face stigma

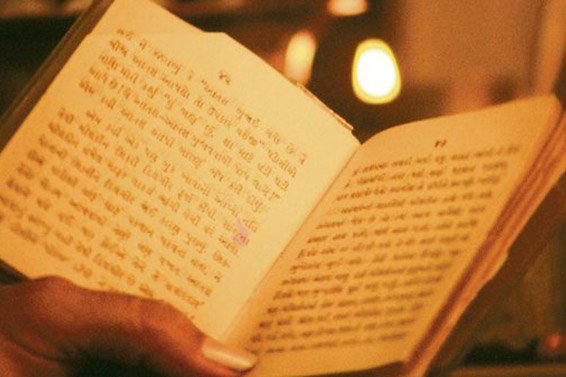

DOHUK, Iraq (Reuters) – Carefully tucking his Farvahar pendant under his shirt, Aram Mehdi reminds himself of the core Zoroastrian principles it represents: good words, good thoughts and good deeds.

Born and raised in a conservative Muslim family, the 31-year-old Iraqi Kurd from the city of Dohuk, in the north of Iraq’s semi-autonomous Kurdistan region, is afraid to wear the Zoroastrian symbol openly.

His friends used to call him ‘Mullah’, Mehdi recalls, as he scrolls through old pictures showing him praying at a local mosque.

But his social network started falling apart when he decided to distance himself from Islam and follow the teachings of Zoroaster, who founded Zoroastrianism some 3,500 years ago in ancient Iran.

Spreading as far as India, it was the official religion of three Persian dynasties until the 7th Century CE. It rapidly declined with the rise of Islam and all but disappeared in Iraq.

“I began to ask myself, is theirs the true Islam, or the Islam that my parents taught me?” Mehdi said.

According to Awat Taieb, co-founder of the Yasna association that since 2014 has promoted Zoroastrianism in Kurdistan and also representative of the faith at the Kurdistan government, about 15,000 people registered with the organisation so far.

Most of them were Kurds converting from Islam, but Arabs and Christians joined the movement as well, she said.

Although the regional Kurdish government officially recognised Zoroastrianism in 2015, converts from Islam remain registered as Muslims at the central Iraqi government, something Taieb does not expect to change any time soon.

Driving towards the newly established Yasna branch in Dohuk, Mehdi said he hoped to find a new community of like-minded converts.

The head of the branch, Helan Chia, asked him whether he would abide by the core principles of respecting nature, its four elements of air, water, fire and earth and mankind before registering him officially as a member.

The focus on the environment and on peaceful coexistence are key elements attracting young people from conservative backgrounds to the ancient faith.

Touring the local four-pillared Charsteen cave, Mehdi said he dreamt of one day undergoing his conversion ritual there.

The director of the Dohuk antiquities department, Hassan Qasim, said it had been a place of Zoroastrian worship in the past, but added that the cave, a classified archeological site, can no longer be used as such.

With nowhere to practise their rites, Dohuk’s Zoroastrians hope to grow in numbers and open a temple elsewhere.