Listen: An imagined recreation of a Hindustani concert organised by a Parsi music group in 1890

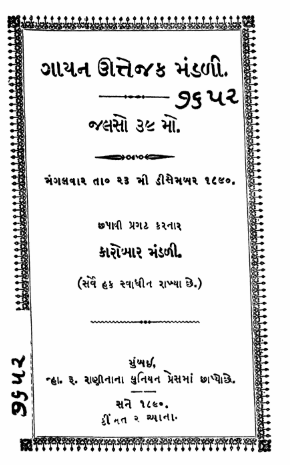

The jalsa organised by the Parsi Gayan Uttejak Mandali in Mumbai had 26 items.

Colonialism may not have displaced the raag-taal paradigm that is so integral to Hindustani music, but it did have an impact on several aspects of music-making in both obvious and imperceptible ways. The classification of musical genres, pedagogy, literature on music, performance contexts, and many more areas experienced major transformations. Naturally, this transformation in turn affected the music and changed the response of listeners to it.

One of the ways in which the colonial impact manifested itself was the manner in which concerts moved out of royal courts and aristocratic homes to spaces that were accessible to those who could gain entry by purchasing tickets or by subscribing to memberships in organisations that hosted such concerts.

For instance, way back in the nineteenth century, the Parsi Gayan Uttejak Mandali, one of Bombay’s earliest music clubs, initiated the idea of concerts open to the public in the city with its formal, ticketed jalsas. A few performers also took an initiative to organise ticketed concerts featuring themselves. In 1897, Vishnu Digambar Paluskar organised a ticketed programme in Rajkot.

As part of formalising concerts and making them more accessible, some organisations even printed programme notes and circulated them among the audience to give a description of the repertoire that was being performed. The execution of this idea, an obvious import from the West, can be observed in a programme note in Gujarati published and sold for 2 annas by the Parsi Gayan Uttejak Mandali for a concert held on December 23, 1890.

As per the note, the concert featured instrumental and vocal music. The format consisted of 26 items divided into two sections, both beginning with instrumental renditions. The first section began with a sitar recital in the raag Kafi and ended with a ghazal composed in the same raag. The second section began with a composition in the raag Khamaj played on the harmonium and the violin, and ended with a tappa in the raag Bhairavi. While most of these compositions may not be known to many of us today, it would be interesting to listen to the raags in the sequence that they are mentioned to get an idea of the sense that the entire concert may have evoked. But for now, we will listen to Kafi, Khamaj and Bhairavi.

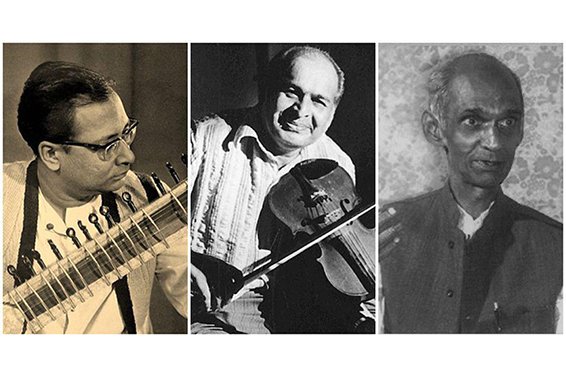

The first track features sitar maestro Nikhil Banerjee. He plays an aalaap in Kafi followed by a gat or instrumental composition in Rupak, a rhythmic cycle of seven matras or time-units. The second composition is set to the 14-matra Deepchandi. He is accompanied by tabla maestro Zakir Hussain.

Renowned violinist VG Jog plays two gats in the 16-matra Teentaal followed by a medley of raags as part of a dhun in the eight-matra Kaherva.

The last track features Gwalior gharana exponent Sharadchandra Arolkar. He sings a tappa in Bhairavi set to the 16-matra Punjabi taal.