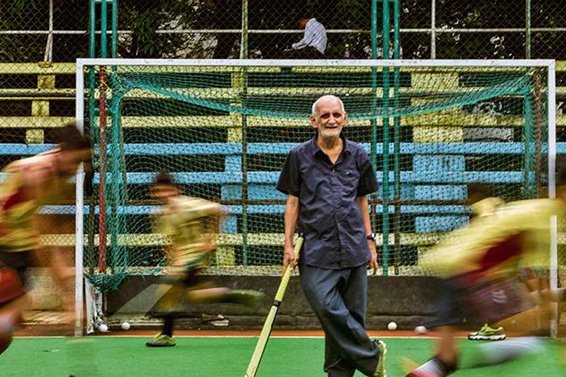

Marzban Patel: Kudos for a lifetime of coaching hockey

Marzban Patel—better known as Bawa—has been doing this for almost 40 years, and he did not change it on August 17, when it was announced that he had been awarded the Dronacharya in the Lifetime category.

Marzban Patel is a small, gaunt man with close cropped hair that’s entirely silver and a toothless smile. Every morning he leaves his small flat in an old and ramshackle Parsi colony in Vile Parle West—where the 67-year-old Patel lives with his brother—and travels by train to Malad, almost an hour away, to coach hockey at the Children’s Academy school.

Marzban Patel is a small, gaunt man with close cropped hair that’s entirely silver and a toothless smile. Every morning he leaves his small flat in an old and ramshackle Parsi colony in Vile Parle West—where the 67-year-old Patel lives with his brother—and travels by train to Malad, almost an hour away, to coach hockey at the Children’s Academy school.

The small squared off area where he is expected to train the children on a cement floor, is hardly conducive to hockey, but Patel does not mind. He’s taken his team to the division one title in the Mumbai school circuit. Once his sessions here are done, he moves to either the compact synthetic turf at another school, St Andrew’s in Bandra, or the centre of hockey in Mumbai, the Mahindra Stadium near Churchgate. Then he travels on the train with his young trainees, seeing them home in the far-flung suburbs of Mumbai and regaling them with hockey stories through the journey, before returning home himself after midnight.

Patel—better known as Bawa—has been doing this for almost 40 years, and he did not change it on August 17, when it was announced that he had been awarded the Dronacharya in the Lifetime category. Bawa was at the Mahindra Stadium, when his phone started ringing with congratulatory messages. He went through his routine and reached home at his usual time.

“Coaching is what I do,” he said. “I don’t have any other life.”

Five of his students—Gavin Ferreira, Jude Menezes, Viren Rasquinha, Adrian D’Souza and Devindar Walmiki—have represented India in Olympics. In the current Indian national team, three players—Yuvraj Walmiki, Alden D’Souza and Suraj Karkare have been trained by him.

“His dedication to hockey is absolute. They don’t make coaches like him anymore,” said former India captain Rasquinha.

“He sees less in one eye now, but Bawa still has the knack of spotting talent,” he said.

Lobo, himself a Dronacharya Awardee, got his first chance to play competitive hockey with the B team of the club Bombay Republicans, which is run by Bawa, and which has produced five Olympians.

Bawa is not a hockey coach in the true sense of the word; he has not played competitively, neither does he have formal coaching training. What he has is old-school—an uncanny eye, a deep understanding of the nuances of the game, and a great reservoir of patience and perseverance that never runs out.

“Discipline comes first for Bawa, he would not tolerate when a talented player would play truant,” says Adrian D’Souza, the Indian goalkeeper who was first scouted out by Bawa as a schoolboy.

“He cajoles, advises and shouts at them to make them work hard during training.”

The annuls of Mumbai hockey are filled with stories of Bawa taking his most talented students all over India personally, to try and get them into academies or to find them opportunities with bigger clubs. Or of him helping players with money to buy shoes, jerseys and equipment.

“Bawa took me to Delhi to get a spot in the Air India Academy. We were six boys, and two of us were selected during those trials,” said D’Souza. “He was well known in Mumbai hockey but in Delhi I realised how highly he was regarded by other coaches. He changed my life as he got me my first chance, he was a great influence.”

The Walmiki brothers, Yuvraj and Devinder, who have both played for India, spent their entire childhood in a tiny garage turned into a home with no electricity, running water, or a toilet.

Their father, who worked as a driver, struggled to make ends meet for his four sons and his wife. The brothers attended a school where Bawa used to coach the school’s hockey team (the school no longer has a hockey programme).

Bawa saw their talent early.

“We had no sticks, no proper shoes or jerseys,” Yuvraj said. “Bawa ensured that we would get all these in time and ensured we practised regularly, at times dragging us from home when we tried to escape training.”

Bawa came to hockey at a difficult time for him personally. It was the late 1970s, and he had just lost his job with a multinational company.

At this point, he met Balram Krishna Mohite, a former national-level referee who had started a hockey club—the Bombay Republicans (because it was founded on January 26)—more than a decade ago as a passion project. Mohite needed an assistant, and Bawa, an incurable hockey lover, jumped at it.

Mohite struggled to keep the club afloat, mortgaging his house and pawning his wife’s jewellery in the process, so Patel was not guaranteed a salary.

“It was Mohite’s passion for years,” Bawa said. “I joined him in the ’70s and took over the responsibility after his death (in 2005). I am happy that I have managed to keep the Republicans going till now.”

With his health failing, Bawa has handed over some of his responsibilities to former Mumbai player Conroy Remedios and his wife Dipika Murthy, a former India woman international.

Bawa, however, continues with his mission of unearthing talent.

“There are many talented players. We have to nurture them and provide them an opportunity,” he said.