Mindful Monologues

Permeated with minimalist brilliance, short film Anahita’s Law highlights issues that plague women in the 21st century.

Taking its name from the ancient Persian mythological deity of water, fertility, healing, and wisdom, filmmaker Oorvazi Irani’s short film Anahita’s Law is an attempt to redefine a woman’s identity in the 21st century. The film that took Irani more than a year to complete started when debates around the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) reached fever pitch in the country. The UCC seeks to replace personal laws based on religious scriptures and customs, with a common set of rules.

“I am not a very political person, but the film highlights political aspects by shining a light on social dynamics, assumptions and women’s movements. I was interested in looking at a woman’s perspective and what it can do to the UCC. The UCC was a contemporary vehicle that brought things into focus, forcing you to go on a journey that explored larger areas of living,” shares the 43-year-old filmmaker. Directed, produced and starring Irani, the film also questions certain fundamental beliefs and perceptions that exist in India’s patriarchal society.

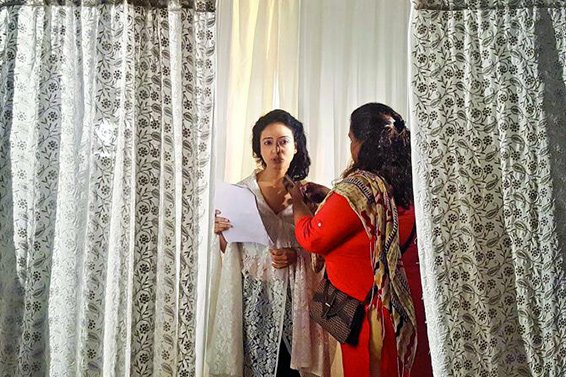

Irani, who says that she doesn’t like to be confined to filmmaking, chose a unique form of narration in order to do something different in her film. So, although the film highlights the problems face by 21st century women, it is narrated from the perspectives of three Parsi women, who lived, suffered and overcame the prejudices of biased tradition. Thus, the film rests on these powerful monologues alone, as it isn’t permeated with dialogue.

“I felt satisfied as a maker when I explored this very minimalist form of the film, which is that of the monologue. I am trying to remove things and bring the language of cinema to its bare minimum,” smiles Irani, who traverses three different age groups, from around 20 – 65, in her performance. According to the filmmaker, a lot of her work centers around two aspects – one, of being a woman and the other, of belonging to the Parsi community.

Illustrating her form of filmmaking, Irani draws a comparison with Iranian cinema that doesn’t have too many filmmaking gimmicks and flourishes. Giving an example, she says, “The film Ten has a scene where a mother and son are conversing in the car, but there are no establishing shots. The camera is only on one face and you see nothing else in the frame. A choice is being made to focus on that one face, therefore pushing the audience to wonder about the other person. It makes you question things, feel curious and claustrophobic, which is required,” she explains.

Likewise, Anahita’s Law is devoid of everything but the bare essentials. “We have this one, specifically-sized frame that exists throughout the film. And in the fixed-sized frame, different universes unfold,” she says. Through her film, the filmmaker promises to take you through different dimensions of time, space and character – both outer and inner – but with certain limitations. “These different characters bring out different dimensions of a woman. So when you look at them together, they tell the story of women,” ventures Irani.

The film, scheduled to release in June, has a prior screening at the National Gallery of Modern Art as Irani wants her film to be part of a larger discourse on art.

“For me, a film is not a specific thing, of course, it has got a unique form, but it gives you the opportunity to bring different things together. The reason I chose a museum space was for this perspective, of how one sees this film. I would love for people to perceive Anahita’s Law, not in the limited perspective of the medium of film but in the larger perspective of art,” concludes Irani.

—On May 31, at the National Gallery of Modern Art, Fort