Discovering Iranian cuisine in Delhi with a ’90s Indipop star

Anaida and Baba Sehgal were the crooners who defined the Indipop generation in the mid- 1990s till Daler Mehndi stormed the charts, and then, Bollywood swung back with the rise of multiplexes, which transformed the cinemagoing experience across the country.

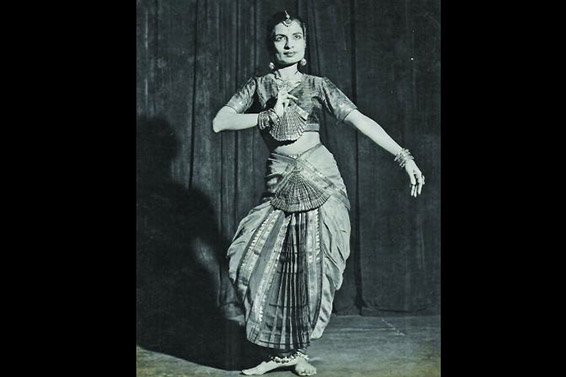

The Indipoppers faded away, but the exotic polyglot Anaida, who’s of Indian-Iranian-Greek descent, and grew up in Abu Dhabi before moving to India at age 14, and sung in 14 languages, has re-invented herself without completely getting out of the music scene.

Dividing her time between Mumbai and Pune, Anaida is now into meditation music and Rumi (you’ll find her work online), painter (her preferred medium is ink on paper), holistic healing, and after completing 32 courses, she’s a certified yoga teacher as well.

And, even though her toned figure belies the fact, she’s perhaps the only exponent of Iranian cuisine (not to be confused with Parsi or Irani) in the country. “I have been cooking seriously all my adult life,” Anaida said, adding that her Iranian-Greek mother, who was also an holistic healer and clairvoyant, was her teacher.

To set the record straight, I asked Anaida if Iranian cuisine was anywhere close to Parsi food. She said they were as different as chalk and cheese.

For starters, Iranians, like Anaida, are “allergic to chillies”. The Iranian and Parsi culinary traditions had to be very different, for the original Parsis fled Persia to escape the persecution that had been unleashed after the Arab invasion of their homeland between the eighth and tenth centuries of the Christian Era.

Since their arrival and smooth absorption into our society, the Parsis have imbibed Indian cooking techniques and a taste for spices. Iranian cuisine too has evolved — and it has been in that state even after the years in exile that Humayun spent in the court of Shah Tahmasp, the longest-ruling Safavid ruler of Iran, and enjoyed his hospitality, which has been recorded in contemporary works of art, showing the Mughal being lavishly entertained by his host.

Humayun is said to have brought back with him a taste for Iranian cuisine, but it was Nur Jehan, Jehangir’s powerful and ambitious Iranian wife, who got the Mughal elite hooked on to her country’s cuisine.

Indo-Persian cuisine struck firmer roots in the royal courts of Awadh and Hyderabad, but the trajectory of the development of Indo-Persian cuisine has been very different from the Irani cafe culture, established by the Iranian Parsis who moved to Mumbai in search of better opportunities in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and Parsi cuisine, whose best expression continues to be the marriage feast.

The point of divergence is the most evident in the “beryani” as it is made in Ishfahan and as we know it in India. The “Esfahan Beryani” is just “fire-roasted” (it is cooked on flat spoons) mildly spiced minced lamb served on a naan.

The word “biryani”, in fact, means “fire roasted”. In India, the land of rice, biryani is a different creature altogether and we have more varieties of it than the number of states and union territories in the country. And the Iranian haleem, which is a breakfast staple in that country, is made with no oil or chillies.

The Iranians use mainly salt, pepper and cinnamon, saffron, which is added liberally to the Shole Zard (rice pudding), rose petals and mint powder (which together lend a new taste profile to their lassi, Doogh), black lime, walnuts, pomegranate, molasses, and khashk (dried fermented yoghurt), which lends a goat cheese flavour to their wheat noodle and vegetable soup (Oshk-e-Reshte) and eggplant rolls (Khashk-o-Badinjan).

And their halwa tastes just like the kadha parshad at the Golden Temple. See any similarities with Parsi cuisine. The two are indeed chalk and cheese.