How food inspires names of India’s Parsis

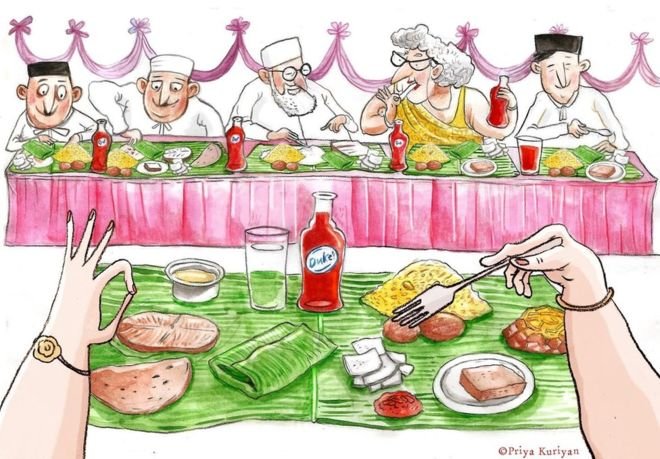

It is no exaggeration to say that Parsis, the Zoroastrians of India, take their food seriously – very seriously.

Love of good food and drink plays a central, oftentimes quirky, role in nearly every aspect of our culture.

When our babies sit upright for the first time, we celebrate by making them sit on top of laddoos (Indian sweet). At Parsi weddings, the clarion call of jamva chaloji (let’s eat!) has a hypnotic appeal.

Weddings are judged almost entirely on the quality of the pulao dal (rice and lentils) and the freshness of the patrani macchi (fish steamed in chutney).

For any other occasion or milestone, we scrupulously avoid fasting, proscribed in our religion as a sin.

Food is etched into our identity, and in many cases it is quite literally written into our names. Indeed, Parsi surnames provide a veritable smorgasbord of edible associations.

One family, with its roots in the western Indian city of Surat, evidently failed spectacularly in the art of cooking and, therefore, earned the surname Vasikusi, which means stinky food.

Other Parsi last names include Boomla, the Gujarati term for the Bombay duck, a slimy fish which has a dedicated fan following in the community, and Gotla, which is a fruit seed.

One particularly unusual variant of surnames ends with the suffix khao, suggesting a desire to eat or greediness.

A Papadkhao, therefore, could be a devoted consumer or hoarder of crispy fried papadums.

The existence of Bhajikhaos (vegetable-eater) demonstrates that not all Parsis were raging carnivores.

Curiously, a number of surnames revolve around cucumbers (kakdi): aside from Kakdikhaos, we also find Kakdichors (cucumber thief).

Many surnames incorporate the suffix wala or vala, which indicates a vocation or association with a particular food or item.

While Sodawaterbottleopenerwala is perhaps the most famous of Parsi last names, numerous others point towards professional vocations in service of good cuisine.

In colonial Bombay there were Masalawalas hawking spices, Narielwalas balancing coconuts, and Paowallas serving up the city’s distinctive Portuguese-influenced bread (and presumably keeping a tab on Paokhaos).

Around the time that Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy, the Parsi philanthropist and opium merchant, introduced ice cream to Bombay (now Mumbai) in the mid-1800s, we begin to hear of Icewalas.

And much later, in the 1930s, a Jeenadaru Cakewala in the city’s Fort district promised cakes that were the “highest in quality and purity”.

Complementing such individuals were Canteenwalas, Confectioners, Messmans, Bakerywalas, Hotelwalas, and Commissariats.

There is, however, some ambiguity associated with such names: the wala suffix could also indicate a fondness for a particular food.

Messrs Akhrotwala, Badamwala, and Kajuwala could have been cornering the market for walnuts, almonds, and cashews – or they could have just really enjoyed eating them.

Ditto for Peppermintwala, Limbuwala (limes), Papetawala (potatoes), Marghiwala (chicken), Biscuitwala, or Paneerwala (cottage cheese).

Food-related last names have also left a unique imprint upon the geography of Mumbai.

In the neighbourhood of Dhobi Talao, you can walk by one Parsi fire temple named after an Idawala (ida means egg) and another that bears the name Sodawaterwala.

Alcohol names

Pitha Street, a small lane near Flora Fountain, derives its name from an old Parsi tavern (pitha).

Pitha Street leads us to an important point: Parsis have also had a longstanding fondness for drink. Aside from consuming liquor, they dominated the trade in spirits across colonial India.

From Multan to Madras, thirsty Indians knew to seek out Daruwalas and Darukhanawalas who ran liquor stores, or Pithawalas and Tavernwalas who operated sit-down establishments.

Some Parsis crafted surnames that specified the precise type of alcohol they sold or produced, such as Winemerchant, Rumwala, and Toddywala. Refreshmentkeepers must have been more ambiguous about their holdings.

By the 1920s and 1930s, the Parsi penchant for liquor became a source of tension with someone who otherwise enjoyed friendly relations with the community: Mahatma Gandhi.

The Mahatma beseeched Parsis to give up drinks and shutter their liquor booths, but very few raised their glasses in support.

Then, in 1939, Gandhi caused Parsis to confront the unthinkable – bidding adieu to their beloved Parsi pegs – as he pushed Bombay’s government to adopt prohibition.

Outraged community leaders creatively argued that a dry law would violate their religious rights and accused the Mahatma of “racial discrimination”.

Some irate Parsis flooded Gandhi’s mailbox with letters written in tones that made the otherwise calm Mahatma blush.

“One writer uses language of violence which certainly brings him within penal laws,” Gandhi stated. Ironically, one of the key architects of the government’s prohibition policy was a teetotaller Parsi, MDD Gilder.

Today, the community has a much bigger problem on its plate. For the past several decades, Indian census figures have chronicled our rapidly dwindling numbers, largely brought about by declining rates of marriage and childbirth. We are an ageing community where deaths vastly outnumber births.

But for Parsis, the love of food has even transcended death. In certain funerary ceremonies, we honour our departed by leaving behind some of their favourite foods at a fire temple.

In order to help reverse our demographic decline, the community has doubled down on holding matrimonial meets for youngsters. Recognising that food can be a potent unifier, organisers of these meets lure in participants with sumptuous meals.

This strategy has met with mixed success.

One Zoroastrian youth organisation recently held a competition to document embarrassing dating experiences, prompting a young woman to write a poem complaining that her date “was interested only in his food plate”.

She won the competition’s top prize: two tickets to – you guessed correctly – a dinner at an upscale restaurant in south Mumbai.

Will such prizes and food-centric matrimonial programmes ultimately yield results?

We hope they do. And we hope that more Parsi youth bond over their abiding love for food, so that a community that lives to eat, lives on.

Parinaz Madan is a lawyer and Dinyar Patel is a historian.