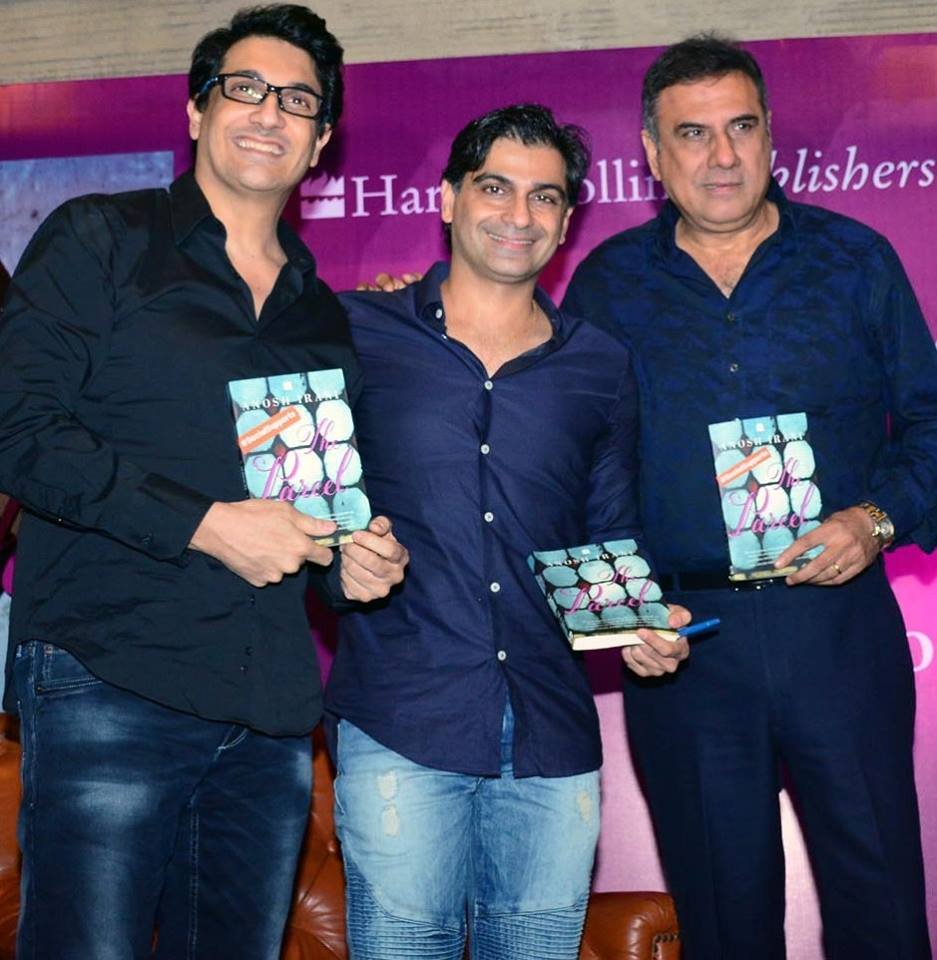

Book review: The Parcel by Anosh Irani – a sordid story of sex for sale in Mumbai and a hard-fought reclamation

Irani presents a compelling and stark portrayal of sex trafficking in Mumbai and unlikely redemption for a transgender prostitute-turned-handler who saves a 10-year old girl from a grim fate

Mud, blood and other bodily fluids: this novel takes no prisoners in its portrayal of prostitution in today’s Mumbai. Yet against this sometimes upsetting backdrop, author Anosh Irani presents a compelling tale of dignity and sacrifice.

The title refers to Kinjal, a 10-year old girl who has been trafficked from her village in Pakistan. She is kept in a cage in the attic of a brothel to prepare her for “opening”. The story, however, focuses more on her keeper, an ageing eunuch named Madhu.

Madhu’s own history is equally tragic. Rebuffed by his parents for being too feminine, the pre-teen Madhu finds solace amid a household of transgender sex workers who have been similarly abandoned. He endures castration to join them as a fully fledged hijra, a member of the third sex which is neither exclusively man or woman, but both.

Sadly for Madhu, the honeymoon period soon wears off. Now identifying as female, she is forced into prostitution where at first she enjoys some success. But as her youth fades away, so do the clients. Infighting among the other hijras means that she can no longer rely on the community for support either.

Persistently denied any real affection, Madhu becomes obsessed by reuniting with her estranged family. An attempt to do so goes wrong. It is only when she is instructed to preside over the initiation of another innocent – “the parcel” – into the sex trade that she realises a way to achieve salvation. The choti batti, the old word for parcel meaning “little light”, literally becomes the spark to the fire which will eventually destroy Madhu and release Kinjal.

Author Anosh Irani grew up near Kamathipura, where the action is set, and his first-hand knowledge of the area is evident, sometimes intrusively. The plot halts temporarily while the rituals and lifestyles of various hijras are detailed. Such information is necessary, however, to reinforce the credibility of a world which is so shockingly horrific that it otherwise might be dismissed as hyperbole. That the parcel is sold into slavery knowingly by her own mother and for less than the price of a goat is just one example.

Irani is at pains to show how “man’s inhumanity to man” extends throughout society. Even the hijras, lowest of the low, operate a hierarchy in which lesser members can be traded between the elite. Simultaneously, Madhu’s own clan is under threat of being made homeless as developers circle their house, spurred on by a property boom from which not even the red-light district is immune.

Irani writes: “For all this prosperity to happen, feet had to be cut off – the human feet of those who could barely walk to begin with. But a greater purpose had arrived: to provide housing for people who didn’t need it.”

Madhu is so entrenched in the system that she too is blinded to the evil in her actions. Despite mentally torturing the parcel, Madhu “believed that what she was doing was humane” as no physical violence is involved.

Madhu is eventually exonerated but other characters are not. While Irani resists lecturing and keeps the novel’s tone matter-of-fact, he is not above directing the jury. He lays responsibility for the iniquities firmly at the feet of parents, or those charged with childcare, who let these terrible events happen.

As another prostitute, Padma, says: “Everything that has happened to me since, has happened because one man failed to think I was worth anything.”

This is Irani’s point, especially dramatised in the scene where Kinjal returns home “unopened” and is still rejected by the villagers. A little more acceptance and understanding, this novel demonstrates, would really make a difference.