Portrait of a people

Khorshed Gandhy and Priya Maholey’s book of portraits of Parsis takes you back to a rich chapter of India’s past

“My name is Droid; one may burn a dordi (coir-rope), but the twist can never be taken out of it.”

— Dadabhai Naoroji to Prince Malhar-rao

I had always admired the Parsis as a community; mostly, however, from a distance. Till I had the unlikely fortune of forming an increasingly warm friendship with Saker and Mehli Mistry. Unlikely, I say, for we live at long distances from each other: I am in Chandigarh, and they live in Mumbai; I am an art historian with an interest in poetry, and their professional fields and interests are quite different, being banking, speech therapy, community service and western music. But it was staying with the Mistris during my more or less annual visits to Mumbai which has led to this friendship. For, it has been these stays which allowed me to sense where their hearts lie, get close to their modes of thought andthe broad-minded of their outlook upon life, savour their warmth and their generosity of spirit.

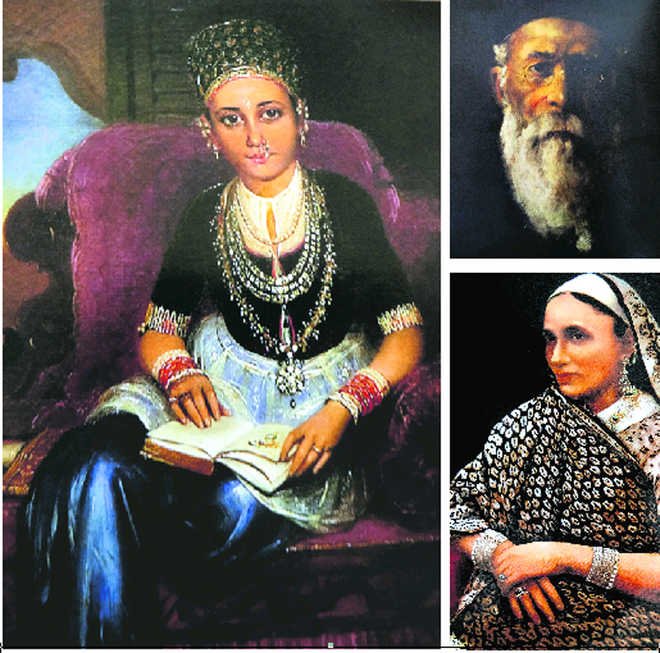

It is perhaps this growth in my admiration, which led me to take down my copy of a book, which had lain on my shelves, and browse through it: Portrait of a Community, Paintings and Photographs of the Parsees, which Khorshed Gandhi and Priya Maholey had put together some years back. To dip into the book was like travelling back in time, for, not only do the portraits that featured in it belong to the past, both in respect of period and style, but they also serve as reminders of some remarkable personages who had in their own ways shaped India. There they were looking out of their portraits at us: visionary industrialists, shipping magnates, intrepid merchants, founders of seminal institutions, philanthropists, men of learning, women of courage and style and enterprise. Predictably, among them there are names that nearly everyone knows: Dadabhai Naoroji, Pherozeshah Mehta, Jamshed, Dorab and J.R.D. Tata, Ardeshir Godrej, Cowasji Jahangir. But there are hosts of other names that are, undeservedly, less known: Jamsetji Jeejeebhoy, Cowasji Jehangir Readymoney, Pestonjee Bomanjee Wadia, Nowrojee Jamsetjee Wadia, Shams-ul-Ulama Jivanji Jamshetjee Modi, Lady Meherai Cursetji Cama. The visage, sometimes, the persona, of each one of them is there to see.

Interestingly, the collection of portraits in this volume was not easy to assemble. For, while some portraits were preserved in the families of the rich and the famous, even of the now forgotten, there were others that, as Khorshed Gandhy noted, ‘hung in dark corners and at immense heights where the reflection of their covering glass proved a great challenge (to photographers)”. Some portraits and photographs had in fact to be borrowed “from dealers who had picked them up from the ‘kabadi market’ that locally passes under the name of ‘chor-bazaar”, the families from which they came having discarded them as junk. But one remains grateful for this act of retrieval, for each portrait has a story to tell not only about itself but also about the India it sprang from.

Hardly any of the portraits, interestingly, is in the traditional Indian miniature painting style or format, nearly everything bearing the imprint of Europe. This, however, is not surprising considering that the Parsi aristocracy was among the quickest in India to take, at least externally, to European manners and style of living. Image after image shows men and women sitting comfortably in European style chairs or standing next to tables on which their hands rest, following approved studio fashion. One also remembers the fact that at the point of time one speaks of — late 18th and early 19th centuries — a number of European painters were active in India, plying brushes in oil, ready to be engaged. The names are well known: Tilly Kettle, Johann Zoffany, George Chinnery, James Wales, Ludwig Fleishmann, among them. The paintings these itinerant painters produced, with “their sheer realism of the flesh tones, the fullness of the bodies, the shimmering ornaments reflecting light, evoked a magical quality”, as has been said. “Good taste” is what they represented for the contemporary Parsi patrons. Gradually, of course, there were Indian painters, trained in the newly founded Art Schools, who had started painting in the ‘good taste’ style. Names had emerged of men with the gift of painting, foremost among them being Ravi Verma, and then, of course, painters like Pestonjee Bomanji, Pithawala and Jehangir Lalkala. The market for realistic portraits in oil was hot.

It is a long and fascinating story, and parts of it will have to be told another time. Meanwhile, there are these fascinating images to contemplate, the most commanding of them being the portrait of that fiercely nationalistic, grand old man, Dadabhai Naoroji: a philosopher-politician who was at one time the Dewan at the court of Baroda, at another, the first Indian member of the British Parliament, but ended up being one of the founders of the Indian National Congress. Somehow, in this portrait of his in old age, one can see him summed up.