Threads of Continuity

A look at Zoroastrian heritage in exhibitions that brought together India, Iran, and the UK

An unusual cultural phenomenon recently unfolded in India’s capital city. From March until the end of May, New Delhi’s prime museums and institutions facilitated a rich programme of events – exhibitions, talks, film screenings, concerts, publications, and even a fashion show – tracing the journey, history, and evolution of the Zoroastrian diaspora. A few weeks ago, I stepped out of the scorching sun into the corridors of the National Museum to peruse The Everlasting Flame, an exhibition providing a visual narrative of the history of Zoroastrianism, jointly organised with the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London, the British Library, and Tehran’s National Museum of Iran.

Though India’s Zoroastrian community is the largest in the world, it is still a micro-minority within the country, with most Indians being aware of it through the names and contributions of its more famous and affluent families. Congregated more in western India and the Deccan, Indian Zoroastrians are called ‘Parsis’, as well as ‘Iranis’, names denoting their origins (‘Parsi’ literally means ‘Persian’, and ‘Irani’, ‘Iranian’). Beginning in the eighth century A.D., Iran’s Zoroastrians began migrating to India in successive waves, following the collapse of the Zoroastrian Sassanian Empire and the Arab occupation of Iran. In the subcontinent, the Parsis became an influential group under colonial rule, eventually migrating to other parts of the world.

I’ve been to the National Museum several times, but walking through the exhibition space – twice – was transformative. After browsing a textual introduction supplemented by objects highlighting the connections between the Sanskrit Vedas and the Zoroastrian Avesta, I stepped into a sonorous dome echoing with hymns from the Gathas of Zarathustra, also inscribed on the walls. There was a section on funerary practices, introducing the Dakhmehs (Towers of Silence) no longer permitted in Iran, but not yet obsolete in India and Pakistan; religious books in Middle Persian (Pahlavi) from the 16th – 18th centuries; folios from Persian epics; weathered, reconstructed artworks from Afghanistan and China featuring the Iranian hero Rostam; the libretto of Mozart’s Magic Flute (featuring the Zarathustra-inspired character Sarastro, as well as Zoroastrian themes); a children’s version of the Shahnameh (Book of Kings) playing in a loop; and an etching of a stone relief from Darius the Great’s palace in Persepolis presiding over a room at the heart of the exhibition. The ceremony of the Yasna liturgies was also explained through videos and ritual objects, and even a replica of an Atashkadeh (Fire Temple) – one of the oldest in Mumbai, adorned with Achaemenid and Sassanian-era motifs – was present. This was easily one of the exhibition’s highlights, as traditionally, non-Zoroastrians are not admitted into Fire Temples.

The exhibition mapped the emergence of the religion in Greater Iran, its promotion to the dominant religion of the Persian Empire, and its journey to other parts of the world following the post-Islam exodus

A short walk away, at the IGNCA, was a second Parsi exhibition, Threads of Continuity, curated by Parzor Foundation Director Shernaz Cama, designer Ashdeen Z. Lilaowala, renowned puppeteer Dadi Pudumjee, and researcher Kritika Mudgal. Focusing on Zoroastrian philosophy and lived heritage, the exhibition took its name from the kusti, the girdle of 72 threads worn by every Zoroastrian from the time of their navjote (initiation) ceremony, which acts as a shield and symbolises the path to truth (Asha), choice, and connection to other beings. Threads also play an important role during the Yasna ceremonies, in marriages (as symbols of union and bonding), and at death, the kusti accompanying the body to the Tower of Silence.

I finally made my way to the NGMA, completing the trio of major museums in Lutyen’s Delhi. It took me two days over two weekends to see all three exhibitions, complete with eager eyes and frenzied note-taking garnering curious looks. Despite all the publicity and uniqueness of these exhibitions, however, museum-goers were few and far between. The NGMA engaged with the Parsi community through the lenses of art and migration. No Parsi is an Island, described as a ‘curatorial re-reading’ of the work of Parsi artists over the last 150 years, traced paintings and sculptures from colonial times to the present. The exhibition explored the metaphysical plight of the community’s members as ‘inhabitants of the in-between’, in a bid to demonstrate how the Parsi artist (and citizen), despite a history of migration, is strongly enmeshed in the fabric of Indian society. There were several sculptures by Piloo Pochkhanawala – amongst the first of India’s few women sculptors – including a maquette of her public installation Spark, which used to adorn Mumbai’s Haji Ali traffic circle, and oil portraits by father-son duo M.F. and Sorab Pithawalla. Other highlights included abstract works, as well as books written and illustrated by Mehlli Gobhai; 10 tapestries and a documentary on the all but extinct ghalamkari textile tradition by Nelly and Homi D. Sethna; drawings and sculptures by Gieve Patel; and giant canvases and old sketchbooks by Jehangir Sabavala, still popular at international auctions.

The theme of wayfaring continued in Painted Encounters, a section of the exhibition that gave the feeling of being transported to another era. A replica of the HMS Trincomalee – the oldest British warship still afloat and now belonging to the Indian Navy Collection – set the tone. The Parsi narrative was interspersed with that of colonialism in an exhibition about maritime migration flowing in two parts, distinguished by walls of maroon and deep blue. One could travel back tin time to learn about the opium trade – in which nearly 50 Parsi families played a crucial role – and the shipbuilding industry common in a community that settled in some of India’s major port towns. Through lithographs, photographs, glass paintings, and objets d’art from bygone times, the displays portrayed stories along the Silk Road, proving that ships and currents were carriers of not only merchants and material goods between Europe and Asia, but also of culture.

‘The Everlasting Flame’, ‘No Parsi is an Island’, and ‘Threads of Continuity’ ran through May 29 at the National Museum, National Gallery of Modern Art, and Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts in New Delhi, respectively.

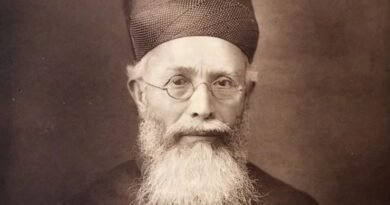

Cover image: William Johnson – Parsis in Plain and Holiday Attire (c. 1855 – 1862).