In a pickle

It’s a great time of the year to pay tribute to these wicked, tongue-blistering concoctions

First the statutory warning: this article might prove injurious to your health. Or, at least, peace of mind.

It has certainly proved troublesome to mine. As I revisit those wicked, tongue-blistering concoctions that have sat at the table in tiny bowls along the years, I’m feeling more than ordinary nostalgia. I’m feeling downright desperation.

There’s nothing quite as addictive as a good pickle. An oily, vinegary Goan prawn balchao, that manages to be sweet, sour and salty in a single mouthful. A bright, mustardy vegetable pickle packed with wholesome carrots, cauliflower and turnip. The tangy lime pickle that slowly discovers its identity after sitting in the sun for months on end. Or the killer creation served in the Northeast and made out of bhoot jolokia — chillies so fiery that if you unwittingly bite into one, you wish you were dead.

This is, of course, a great time of the year, to be pickle-hungry. For however much you love your north Indian green chilli pickle and limbu chatpat from Bohra Mohalla, you have to admit that mango pickles pack a special punch. And even as I write this piece, tart green mangoes have started appearing everywhere. On the branches outside my window. In tantalising heaps in the bazaar. And, hopefully, in the kitchens of all those kind people who make countless jars of fresh pickle and then generously send them to friends and neighbours.

All those aunties from Andhra Pradesh who spend tedious hours, choosing the sourest, firmest mangoes, chopping them into equal pieces, sun-drying mustard seeds and chilli, and then creating the perfect avakai pickle – one that is not just spectacular, but will stay the entire year without getting spoilt. Or the busy Gujarati households that come together to grate and giggle every year, as they turn out endless barnis of sweet mango chhundo to be consumed with thepla for many months.

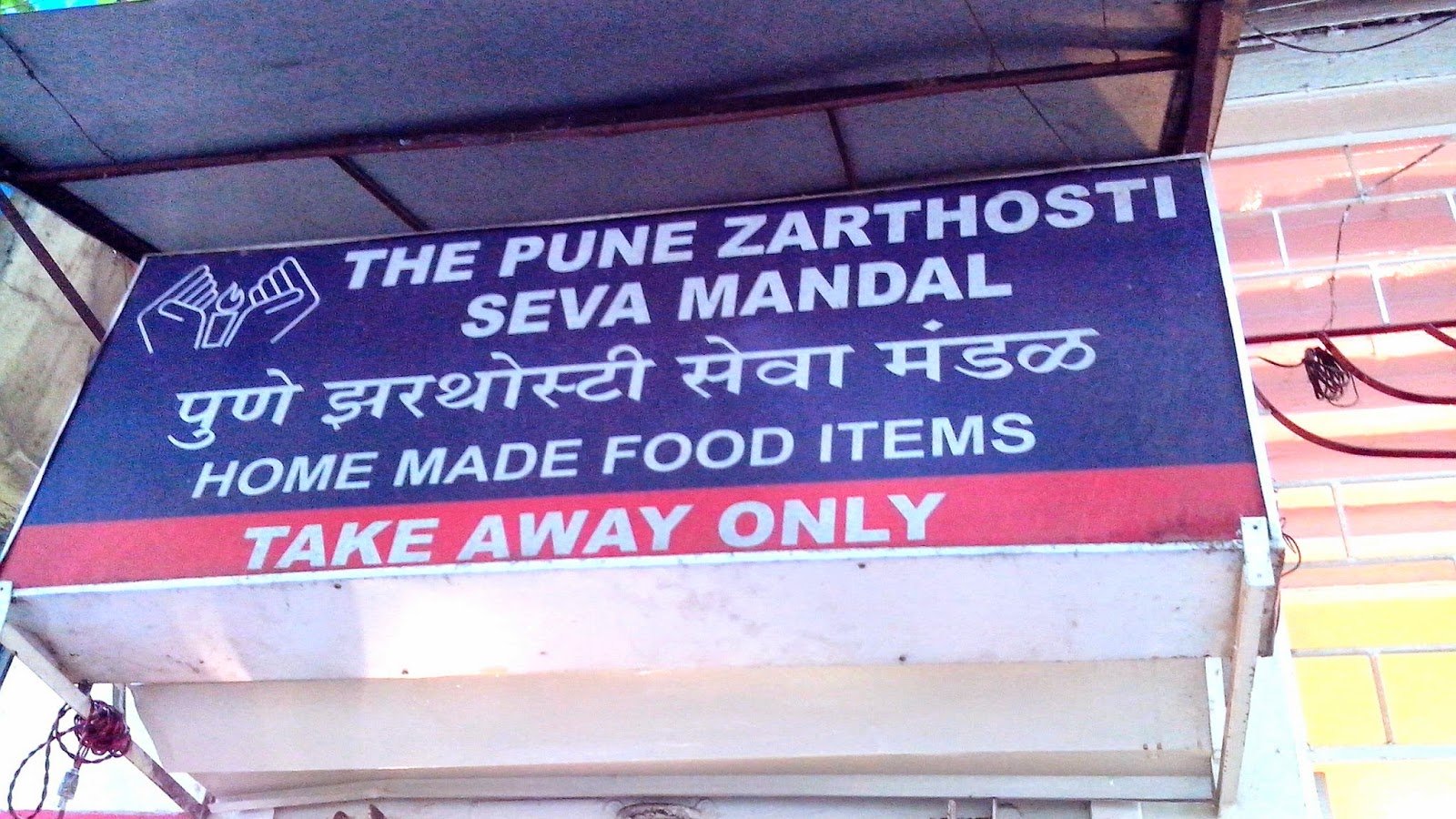

This is the time of year when rare bottles of Parsi buffena — made from whole, ripe mangoes — pop up in the Princess Street shops for a brief period. When the hordes descend on Taheri Stores in Bohra Mohalla, to taste the first gorkeri and spicy mango creations of the year. When terraces in Tamil Nadu will be witnessing that unmatched magic — the gradual transformation from mangoes and spices into a mindboggling thokku that elevates simple dahi-rice into a feast. When even quick-fix families like mine succumb to the mood, buy a packet of Bedekar masala and fill at least a couple of jam jars.

After all, it’s fun to be part of a tradition that seems to have begun more than 4,000 years ago. Before the days of refrigeration and canning, it was essential to find ways to preserve food. The problem was solved by drying fruits, vegetables and even meats in the sun with salt or brine. By 850 BC, Aristotle was praising the curative power of pickled cucumbers and, later, Roman emperors were feeding them to soldiers in the peculiar belief that they imparted special strength. Presumably, Indian philosophers and kings were also fans of our very own, incredibly sophisticated pickles. KT Achaya, that marvellous food detective, describes a Kannada work from 1594 that lists 40 varieties of pickle — involving not just mango and limes but also brinjals, fish and pork.

That’s just the tip of the ‘spiceberg’. Each community has its quirky specialities. My Parsi forefathers are best known for their rich, carrot-based lagan nu achar, which, as its name suggests, is a staple at wedding feasts. But the Parsis also make a stunning pickle with fish roe and the indispensable Navsari sugarcane vinegar. While my Bohra grandmother cooked up massive pots of mithu ichar — a 10-minute recipe involving dates, vinegar, jaggery, raisins, zardalu and Kashmiri mirchi. Fabulous with rice and chicken curry, but equally good as a topping for toast and scrambled eggs.

Then there is that wonderful north Indian kala nimbu ka achar that involves lime, masalas, lots of sun and even more patience. Whole limes are mixed with spices and left in the sun for a couple of weeks. Then the bottle is shoved to the very back of a dark cupboard for a year. After which it is retrieved. The blackened gunk is tasted, and the salt and sugar is adjusted. After which it returns to the cupboard for a couple of years at least.

Every region has its unique pickles. And most families seem to have their own precious recipes. For those who don’t, never fear. You can follow my example. All morning I’ve been taking breaks from writing this column to fill virtual baskets. I’ve just discovered a site called the Thenortheaststore.com and have ordered one king chilli pickle, one bird’s eye chilli pickle and one chicken pickle. (The highways in the Northeastern states are lined with tempting roadside shops selling multi-coloured pickles. During a recent trip to Meghalaya, I stocked up with glee, only to have my precious bottles confiscated at the Guwahati airport. So I feel entitled to this splurge.)

Then, while I’m at it, I find another site called GoanPickles and behave badly again. And, right now, I’m figuring out how to organise some Tarapori patio made from dry Bombay ducks. And wondering if there’s anybody driving past Padma Guesthouse in Kolhapur, who might obligingly get me a packet of mutton lonchhe.

After which, I will happily live on dal, rice and pickle for the next three months.

Mutton pickle

- 500g boneless mutton cut into small cubes

- Salt to taste

- 1/2 tbsp turmeric powder

- 2 tbsp ginger-garlic paste

For dry roast:

- 1/2 tsp fenugreek seeds

- 1/2 tsp cumin seeds

- 1/2 tsp coriander seeds

Other ingredients:

- 2 tbsp red chilli powder

- 250 ml oil

- 5-6 lemons

- 3 garlic pods

1 Dry roast the methi seeds, cumin seeds, coriander seeds. Once cool, grind them into a powder. Make a paste with the garlic.

2 Wash the mutton, then marinate in salt, turmeric powder and ginger-garlic paste for about 10 minutes. Then roast the mixture for about 10 minutes until there is no water remaining in it.

3 Take a wok, add oil and heat it. Put the roasted mutton into the oil and fry till golden reddish. Add red chilli powder and mix well. Add roasted masala and mix. Then add garlic paste and mix thoroughly.

4 Add plenty of lemon juice and then cook on simmer till oil separates. Do not overcook as the masala may stick to the base.

5 Once it cools, store in a glass jar and refrigerate for up to a month.

Published on The Hindu Business