Tales of broken lands

Armenia, Syria, Bengal – the locations may change, but the unfulfilled longing for a home that is lost remains the same

As she peered at the old photograph, the elderly Armenian woman could not hold back her emotions. She clasped her hands together, muttering and shaking her head in disbelief. The photograph depicted children standing in a row on a stage, perhaps for a school performance. Tears rolled down her cheeks, as she stroked the glass that protected the photograph, her fingers seeking out a little girl in a bonnet.

The photograph was taken in 1932 and was part of an exhibition collection called ‘Armenia 1915 Centenary of the Genocide’, displayed at the Paris City Hall in May 2015. Anna, the elderly woman, like other Armenians, had come to see the exhibition commemorating the anniversary of the Armenian genocide, a key event in the history of the 20th century. She had fled Armenia in West Asia as a child along with thousands of people in the wake of the violence unleashed by the Turks of the Ottoman Empire and had grown up in refugee camps in France. Now in her 80s, Anna recognised the little girl in the bonnet. “That’s me!” Anna exclaimed and dragged her daughter to show her the photograph. Both were pleased that an Indian showed interest in the exhibits and posed for a photograph with ready smiles.

My interest stemmed from the fact that a few thousand Armenians had escaped to India during the period; at least 2000 of them ended up in Kolkata. Since colonial times, the city was a thriving cosmopolitan business hub attracting communities from all over the world. During the 19th century, Kolkata had been broadly divided into the British ‘White Town’ and the Bengali ‘Black Town’. The Jews, Chinese, Greeks, Parsis, Armenians and the Portuguese lived in pockets between these segregated spaces, peacefully co-existing with the local populace. The sacred flame of the Parsis’ Zoroastrian fire temple continues to burn since 1912 in central Kolkata, sharing street space with the Aga Khan Jamatkhana, where people from the Ismaili community gather to pray. Unlike in the rest of Europe, the Jewish community were not persecuted in India, and so their numbers grew in Kolkata during World War II. As far back as the 18th century, the Baghdadi Jews came as traders and settled in the port cities, including Kolkata, and advanced their social and economic ambitions. Each of these immigrant communities thrived and started their own schools, places of worship and even newspapers.

While growing up in Kolkata during the 1960s and 1970s, Bengalis interacted sporadically with immigrant communities like the Armenians, Jews, Parsis and Chinese. But these interactions were limited to buying confectionary from the Jewish bakery Nahoum and Sons, tucking into dinners at the fabled Fatty Mama’s Chinese dhaba or buying personalised handmade high heels after getting our feet measured at Li’s in Bentinck Street in central Kolkata. I did not have any Armenian friends. As children, the closest we got to the Armenian community was when we peeped through the high iron gates of the Armenian school tucked away in Free School Street, off the fashionable Park Street. We could only catch a glimpse of the sprawling playground within the compound, and we used to plot about how to sneak in. We would eavesdrop on casual conversations our elders would have on how the Armenians were a wealthy business community, comprising mostly of merchants and builders, who “owned more than half of Park Street”. We learnt that the posh parts of Park Street that housed the restaurants and night clubs, forbidden to us even as teenagers, and majestic buildings like Park Mansions and Stephen Court were built by Armenians. There were stories galore of their wealth, real or imaginary, deposited in Hong Kong banks and how they took care of their own people. We would fantasise about becoming friends with a generous Armenian who would treat us to sumptuous cakes and chocolates from the famed Flury’s cafe.

Later, we discovered that Kolkata’s ties with the Armenians are even more deep-rooted than we imagined – the city owes its ‘existence’ to them. The Armenians are said to be the first settlers in the area now known as Kolkata, long before Job Charnock of the British East India Company set foot on the banks of the River Ganga in 1690, upsetting the long-held belief about the ‘birth’ of Kolkata. The tomb of an Armenian woman located in Church of Nazareth on Armenian Street in central Kolkata reveals she died a full 60 years before the arrival of Charnock, the ‘official’ founder of the city. The inscription reads: “This is the tomb of Rezabebeebeh, wife of the late Charitable Sookias, who departed from the world to life eternal on 11 July 1630.”

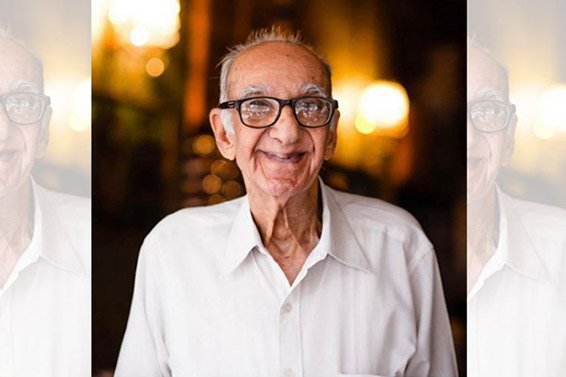

The first time I met an Armenian was in the late 1980s when, as a reporter, I decided to do an article about them. The few I met were all ageing, deeply fond of the city and nostalgic about the times gone by. I remember meeting a kind and humorous elderly gentleman who was living with an equally old Jewish man. He joked about their living arrangements – where else would I find a Jew and a Christian caring for each other! There were couples at the old people’s homes who recalled flowing silk gowns and dancing in grand halls under chandeliers and about how they were now taken care of by their own people. Their only complaint was loneliness, since thousands had left the city for better opportunities.

This pattern of exodus, where many foreign-origin families and Anglo-Indians immigrated to other countries, was noticeable following India’s Independence in 1947. Thousands of mixed-race Anglo-Indians faced an identity crisis and uncertainty when the British left the country. From the 1950s, armed with British passports, they migrated in large numbers to the Commonwealth countries of Australia, Canada and New Zealand. Many Jews left in pursuit of their new homeland, Israel. The relationship with the Chinese community soured considerably when thousands were interred in camps set up in Rajasthan’s desert during the one-month border conflict with China in 1962. Though the Chinese in India had become Indian citizens, they were suspected of being spies and were detained without trials; many left dejected for Canada and Australia. The Indian state, till date, has never apologised for the excesses committed at the time. The Armenians left around 1992, when Armenia became an independent country. Today, only a handful of them remain in Kolkata.

Click here to read more on Himalmag.com