A common cause in personal laws and gender rights

On Friday, just before the weekend, the Jamiat Ulema-i-Hind (JUH) knocked on the doors of the Supreme Court asking to join a barely begun public interest litigation that has the potential to change the way we view personal laws and how they stack up on gender rights.

The organisation of Islamic scholars, which claims a membership of 10 million across India, told the apex court that the source of Muslim personal law was the Holy Quran and thus does not fall under the expression “law in force”.

In October, a two-judge Supreme Court bench raised the issue of “gender discrimination… which concerns the rights to Muslim women”, ironically, while hearing a bunch of petitions concerning the rights of Hindu women who wanted to know if the Hindu Succession Act of 2005 would have retrospective effect.

It’s early days yet and the Supreme Court has asked the attorney general for assistance in examining the rights of Muslim women. But by asking to join the public interest litigation, the JUH has staked its claim in an old argument that insists that personal laws are inviolate.

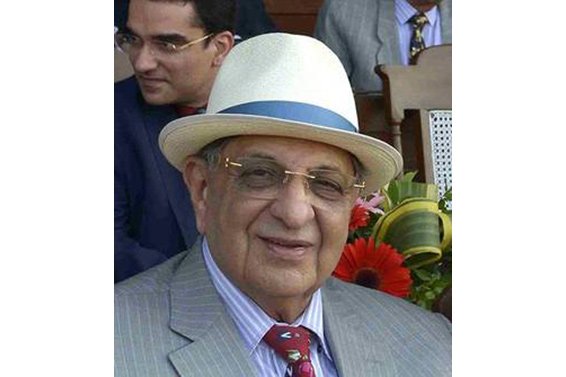

Thirty-one years ago, the JUH and the All India Muslim Personal Law Board had opposed granting maintenance to Shah Bano, a 62-year-old divorced mother of five whose husband had taken a second wife. Under Muslim personal law, husbands are obliged to pay mehr—an agreed sum of money at the time of marriage—and maintenance for roughly three months, a period known as iddat.

It was largely to placate the Muslim orthodoxy that the Rajiv Gandhi government passed the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights Under Divorce) Act, 1986, that overturned the Shah Bano judgment. But in a series of judgements ever since, starting with Danial Latifi (who in a strange twist, turned out to be Shah Bano’s lawyer), the Supreme Court has generally remained consistent to the principle that Muslim women have the right to invoke fundamental rights granted to them by the Constitution.

It’s not just Muslim personal law. Mary Roy succeeded in 1986 to strike down the Christian law of inheritance that discriminated against daughters. Last year, the courts questioned why Christian couples filing for divorce by mutual consent were required to be separated for two years instead of just the one year that applies to other communities. Even now, pending before it is a petition filed by a Parsi woman who has asked why her marriage outside her community has resulted in her forfeiting the right to worship at her fire temple.

The idea of a “uniform civil code” that will govern all Indians in matters of inheritance, adoption, marriage, divorce and maintenance remains a directive principle in the Constitution. In the nearly seven decades since Independence it has become a loaded term that, apart from a mention in the Bharatiya Janata Party’s manifesto, barely makes it to public discourse.

But first, two misconceptions need to be dispelled.

The first is that a uniform civil code will be a Hindu majoritarian one. Let’s not forget that Hindu women have also had to battle for legal rights, and continue to do so. The Hindu law reforms of 1956 were bitterly opposed by the Jana Sangh and even then stopped short of granting women a right to family property. That came about only in 2005, and it was as recently as last month that the Delhi high court finally held that the eldest daughter can indeed be a “karta” of a Hindu Undivided Family (HUF). But under a common code, what, for instance, would happen to the HUF, which, in fact, grants an advantage to Hindus by way of tax exemptions?

The second is that personal laws somehow “appease” minorities. This argument forwarded most often by the patriarchal Hindu right is so utterly ridiculous that nobody ever bothered to ask Muslim women what it was that they wanted. Last year, the first-ever survey of nearly 5,000 Muslim women found that close to 90% opposed both polygamy and triple talaq. So, when you talk of “appeasement”, then who exactly are these discriminatory laws appeasing? Not the women of the community, surely.

At a time when women across faiths are questioning orthodoxy by, for instance, insisting on their right to unfettered access to places of worship, the debate on gender disparity in personal laws is not out of place. But let’s be clear, it must be a debate that will look at discriminatory laws and practices in all religions.

A good starting point then is not a paternalistic and patronizing “plight of Muslim women” position. A good starting point is recognizing that the world has changed and along with it notions of social and gender justice. An ideal solution would be for reform from within religious communities. Failing that, of course, there’s always the courts.

Published on Live Mint