Love in Junagadh

Keki Daruwalla’s moving novel is a celebration of pre-Partition history as well as his childhood.

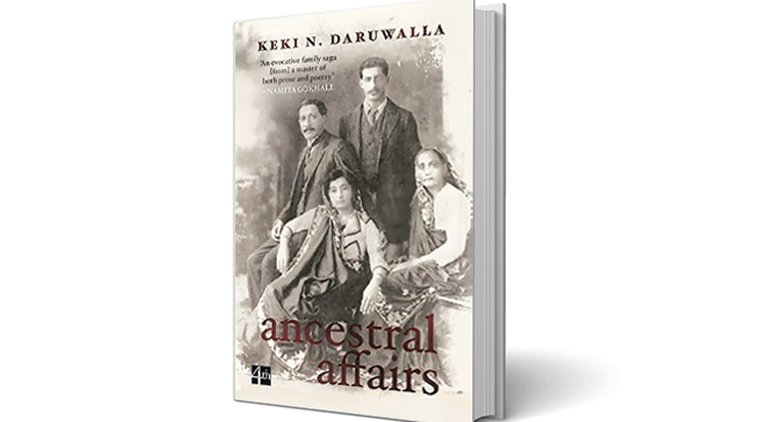

Title: Ancestral Affairs

Author: Keki Daruwalla

Publisher: Harper Collins

Price: 499

Pages: 243

By Rukmani Bhaya Nair

There are Raj novels and then there are Swaraj novels. Kipling’s Kim, EM Forster’s Passage to India and Paul Scott’s The Jewel in the Crown are examples of the former while R.K Narayan’s Waiting for the Mahatma and Mulk Raj Anand’s Coolie emblematise the latter, with Salman Rushdie significantly updating both sub-genres with his fantastical Midnight’s Children. Keki Daruwalla’s second novel, Ancestral Affairs, could not, therefore, have asked for a finer literary lineage — and he does it proud. Daruwalla’s accomplished rendition of India’s fraught 20th century history in one of its smaller pre-Partition Muslim states, to my mind, makes his book well worth reading in the 21st when India is, once again, rethinking its global role as well as engaged in a fierce internal debate on contesting definitions of nationalism.

Still and all, we do not primarily read stories for the light they throw on realpolitik. We read them because they move us. What moved me in this book were its set of love stories and its uncompromising first-person voices — a Parsi father and son narrating the story of their fractious lives in alternating monologues. Also, its charming, poetic descriptions of flora (“delphiniums spearing upwards”) and fauna (“a bird drift of quail, a fall of falcons”) and the irreverence of its language (“Fort for Making Seafaring Enemy Shit in Panty”). This short review will not allow me to dwell on the novel’s pervasive and self-conscious play with language but I will later return for a bit to the robust themes of ancestry and love that animate it. Let me begin, though, with its central player — not a person at all but a state and, perhaps, a divided state of mind as well.

Junagadh, the British protectorate that began by acceding to Pakistan but changed its mind, so to speak, and finally became a part of India, is the lovingly depicted location that allows key historical players like Shah Nawaz Bhutto, the Dewan of Junagadh, V.P Menon, Sardar Patel and others to make plausible cameo appearances in the novel. A tapestry of minor characters, some swashbuckling, some shabby — from nawabs to colonial sahibs, Turkish pashas to Afghan Pashtuns, and Chinese opium traders to hooch traders in Kanpur also enrich the weave of this novel. In this respect, Daruwalla’s deft fictional use of the historical archive impresses. What is unexpected, however, is the initial expression of gratitude in his ‘Acknowledgments’, preceding even his debt to MN Buch, on whose father’s private papers Daruwalla relies in his research.

Now, it is commonplace for writers to declare their childhood as the truest source of their inspiration, but it is unusual, if not unique, for an author to directly thank his: “I wish, firstly, to thank my childhood for the four years I spent in Junagadh from 1945 to 1948”, Daruwalla declares without equivocation. Thank one’s childhood? How exactly does one manage that? Well, through a grown-up celebration maybe — which is just what this book is. Every Indian reader will recognise at once the twin births cradled by the dates Daruwalla cites. Thus, the far from trivial task that he has set himself is to look back at that complex time not as a wide-eyed child but as an emotionally informed adult — which brings us back, I think, to the perennial subjects of love and inheritance that are so intimate a part of Ancestral Affairs.

The affair between Claire Barnes, wife of a well-off British trader, and the lawyer-hero of the novel, Saam Bharucha, includes all sorts of exciting romps, not just vigorously sexual but extending to the lure of property, arson and a semi-evil adversarial cousin appropriately named Neil Blackthorn. Spanning decades, it comes, surprise, surprise, to a happy ending in the present. Likewise, his less than tractable son Rohinton’s affair with his clever and complicated fellow Parsi, Feroza, ends satisfyingly. Indeed, if I were to fault Daruwalla, it would be for the godly ease with which he manipulates the plot, killing off, for instance, inconvenient husbands in a jiffy — both Claire’s and Feroza’s, and finally even Rohinton’s quietly divorced wife, Zarine. Yet, are these not the contrary freedoms that fictions afford us? In an age of “metro-reads” which demand so little effort — or love — from their readers, one should be very grateful indeed for what one might call the back-to-history “retro-read” that the nicely imagined Ancestral Affairs offers.

Published on The Indian Express