Chronicler of a community

Author Cyrus Mistry, recipient of the DSC Prize in 2014 tells Apoorva Sripathi why awards matter and why being reticent helps him write better

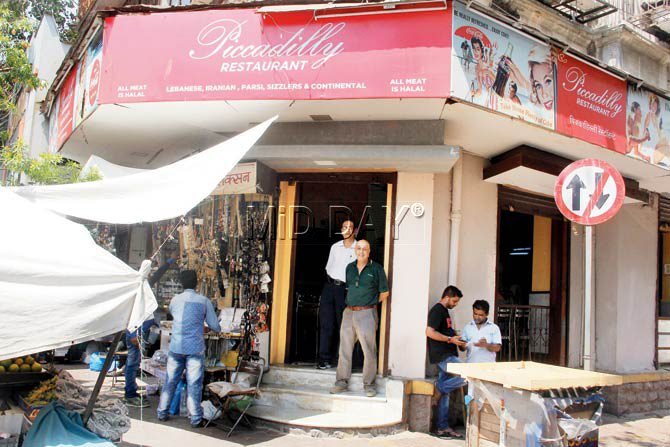

Winning the $50,000 DSC Prize in 2014 for the Chronicle Of A Corpse Bearer changed certain things for Cyrus Mistry. For one, the writer says, he isn’t as far from the madding crowd as he’d like to be. And he’s one of those writers to whom awards mean a great deal. The 59-year-old author, who started out as a playwright (his play Doongaji House won the Sultan Padamsee Award when he was 21), dabbled in almost all forms of writing: journalism, film screenplay, dialogue and documentary before settling on fiction. Although his first novel The Radiance of Ashes — a powerful story about a drifter in Mumbai searching for the meaning of life — was shortlisted for the Crossword Prize (2005), it was Chronicle… that put him in the big league. Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer deals with the idea of ritual purity and practices of the Khandhias or the Parsi corpse-bearer community. Currently living in Kodaikanal and working on his third novel, Mistry talks about, with measured care, on what awards mean to him and why.

Do awards matter to you?

One thing that I’d like to point out is that in this part of the world there’s not much readership for English writing. Whereas in England or America, there are lots of prizes and awards. And for anyone starting fresh, this can give affirmation and boost self-esteem. Then there’s also the problem of money and money is worthwhile. In another sense, the confirmation that the writer has some value, helps. There’s considerable publicity surrounding the event as well.

Did winning the DSC Prize influence you in any way?

No. I’ve been writing for many years now; since my late teens from when I decided to be a writer. The problem is in earning a living. I was a freelance journalist and that takes up time and energy. The award definitely helped in the ease of my writing and made me confident and because of that I was able to take more risks. This (Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer) itself was an experiment, writing about one community on a small microscopic canvas. To take that canvas and raise large questions was metaphorical: people aren’t familiar with the community I was writing about. But it worked because of the tiny focus of the novel. I was surprised when John Ralston Saul (then President of PEN International) spoke about the book at the ceremony — it confirmed that what I had written about had a global appeal. Then again, immediate experiences have a chance of universal appeal.

You are known to be reclusive. Did winning the award change that?

Well, it did. For several months after, I was kept busy by journalists like yourself. But it was a pleasant change. I’m not articulate enough in front of many people and the three-city tour loosened me up a little: I had pretty good conferences and it helped me a lot.

Is it imperative to be reticent to write better?

Yes, definitely. It’s true for all writers. I’d rather put it down on paper than talk to people; being on my own helps me write. So I cannot talk about what I’m working on now, I’m slightly superstitious that way. If I talk about it before it’s formulated on paper, I feel like I have squandered it away by talking about it. I can’t even begin to express the idea behind the book!

You’re a playwright and a journalist; you’ve written a short story (Percy) which was then made into a film for which you wrote the screenplay and dialogue. Do you believe in experimenting with diverse forms?

It’s all because of my career. I still enjoy theatre as a form. In fact, I have an incomplete play I want to finish after the novel I’m working on. And then the short stories happened because I didn’t believe I’d write a novel. But if one has to try and earn a living, the novel is the best form; it’s the only form people are willing to pay for. I was lucky when it came to my first novel — Picador UK gave me a large sum of money, based on the first three chapters, to complete it. And my second novel won a prize.

Did your community have a strong influence on your storytelling?

Yes. In a way, when I began writing short stories, I thought of writing on what I knew best. Before me, there wasn’t much on the Parsis. Later on, my brother (Rohinton Mistry) took it up. My first book’s protagonist is a Parsi, but he’s a maverick and doesn’t live like one.

Which brings me to your third novel — will you include a Parsi character in it?

I get away by writing about Parsis (laughs). My third novel doesn’t have a Parsi. But it’s somehow not weird — all my life I’ve written about them. I’m quite bored, actually.

Published on The Hindu