Cheers To Lal Chimney

It’s a privilege I haven’t had. Of living in a baug, that quaint yet quintessential bastion of Parsidom, the housing hub whose clusters across town are home to over half the 40,000 members of my community left in the city they virtually built.

Still, always a connect somewhere for everyone. Mine is with Mumbai’s only unwalled baug – Dadar Parsi Colony — where my parents grew up till they got hitched and preferred having kids in the cosmopolitan climes of Bandra. My cousins continue to occupy facing family apartments in ancestral acres near Five Gardens, on either side of the statue of Mancherji Joshi, my mum’s grand-uncle and founder of this colony of leafy lanes.

I’ve discovered the delights and denizens of Navroze Baug, Rustom Baug, Shapur Baug and Captain Colony as I researched books on Parsi theatre and language. To these I add Marzban Colony. Quietly gentrifying a dull Bombay Central stretch neighbouring Nair Hospital, five low-rise buildings of one-bedroom and bathroom units make up this colony named in the 19th century after Muncherji Marzban, a BMC engineer who promoted housing for the poor.

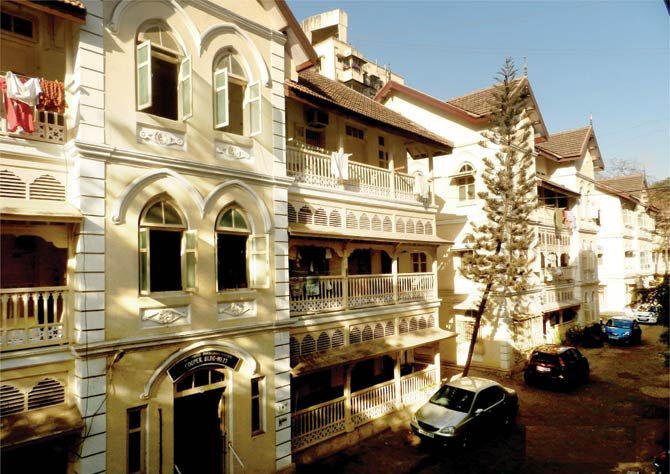

Located in what’s come to be colourfully called Lal Chimney Compound, because a red chimney once rose here, this baug sets a superb example of true trusteeship. Garib Zarthostiona Rehethan Fund (GZRF), the Trust running Marzban Colony, may be Mumbai’s only landlord to renovate rather than demolish — at zero cost to tenants. With results creative enough to earn the UNESCO Asia-Pacific Heritage Award in 2013, three years after a thorough structural revamp was initiated. “There is joy dealing with simple buildings,” says architect Vikas Dilawari of his unusual refurbishing assignment. “For us it was a free hand given, no corners cut. Like-to-like materials brought back old glory — using Burma Teak wood, redoing the ornamentation and cornices.” Embracing the challenge of working wonders with dilapidated structures, his team fully opened, tarred and tiled the five roofs, repaired the shell of the buildings, revived facade carvings, uncovered original balustrades, redid plastering along staircases, overhauled electrical wiring and replaced sewage pipes.

A fact to puff with pride about: Mumbai is ahead of the country in conservation efforts, with 16 buildings restored by UNESCO awarded architects. Dilawari has won this recognition for nine projects including the Rajabai Clock Tower, Bhau Daji Lad Museum and Royal Bombay Yacht Club. Technical achievement apart, UNESCO entries are picked for how well projects understand and reflect the spirit of a place, appropriate adaption, the projects’ contribution to local surroundings, their cultural and historical continuity.

While restoration of the Yacht Club renewed a Neo-Gothic monument and coastal landmark, stated the 2013 UNESCO citation, the conservation of buildings which form the Lal Chimney Compound has safeguarded a distinctive late 19th-century typology that had been in a ruinous condition.

But there’s a danger of seeing this fine specimen of community housing in isolation. Work of the type willingly undertaken by GZRF needs way wider reach and replication. “Mumbai has many unloved, uncared for buildings,” declares Dilawari. “It is only when someone looks after them that we realise what beautiful architecture we have inherited.”

Published on Mid-Day