Parsis In Pakistan: Beloved But Left Behind

Their loved ones may have migrated or passed away, but for many elderly Parsis, the community is there to provide support

There was a royal feast at Aunty Villy Engineer 96th birthday. There was cake, and there was suuji ka halwa too. Everybody inside the Parsi General Hospital came to the party; Aunty Nargis Gyara, Aunty Khorshed Malbari and her sister too. Then there were Gulbanoo Bamji and Homy Gadiali, secretaries of the hospital. The men from the male ward came too. So did the doctors. And the physiotherapist. All the attendants too. Nobody wanted to miss it.

And why would they? After all, Aunty Villy is a superstar. Some boast that the 96-year-old Parsi woman was the first lady admiral of the country’s navy. But Aunty Villy dampens all such talk. “You know I don’t like boasting,” she says dismissively.

And why would they? After all, Aunty Villy is a superstar. Some boast that the 96-year-old Parsi woman was the first lady admiral of the country’s navy. But Aunty Villy dampens all such talk. “You know I don’t like boasting,” she says dismissively.

Outside her ward, in the corridor, the evening shuffle begins to pick up. It is almost time for tea, and some of the other women have already secured their place on the benches.

On one of the benches are Aunty Nargis and Aunty Ami Jeriwalla, two sisters, both spinsters, now living in one of the wards. “People ask us why you didn’t get married,” exclaims Aunty Nargis. “But then they tell us it was the best decision of our lives!” In terms of agency and choice, the Parsi women living in Pakistan were well ahead of their times.

The chatter in the corridor steadily grows louder.

Meanwhile, the men lodged in the adjoining male general ward are only beginning to rise from their afternoon slumber. Word has spread though that teatime is nigh; there is some shuffling on the beds and some make an effort to sit up. Nobody has bothered to switch on the television till now.

A little later, a male patient from a private ward heads outdoors to smoke a pipe. He chooses the entrance by the main road to smoke, while an attendant keeps him company. The noise and smog around him don’t seem to matter; this is an evening ritual that must be performed.

The 30-bed Bomanshaw Minocher-Homji Parsi General Hospital, commonly known as the Parsi General Hospital, is a pre-Partition facility that was built to provide subsidised quality healthcare to poor Parsis and was run by the Bomanshaw Minocher-Homji Parsi Medical Relief Association.

Although the hospital was inaugurated in 1942, the association expanded the premises as needed. “We didn’t have the 30 beds that you see today, we just had three rooms. We didn’t have the population either that necessitated the setting up of a larger facility,” explains Homy Gadiali, secretary of the association. The infirmary, for example, was set up in 1965.

But the story of the Parsi General Hospital and its inhabitants perhaps mirrors the fortunes and fate of the Parsi community in Karachi.

They were once the crème de le crème of Karachi society and polity, with the city’s first mayor, Jamshed Nusserwanji, also hailing from a Parsi family. Those admitted to the hospital today are all septuagenarian, octogenarian or nonagenarian; many would have seen Nusserwanji and witnessed how the city evolved too.

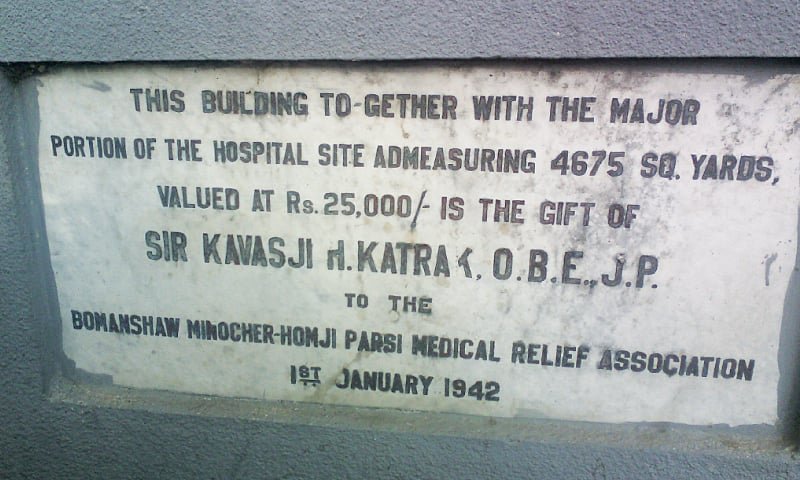

“The land for the hospital was donated by Sir Kavasji Katrak in 1942. He was the gentleman who built the bandstand at the Jehangir Kothari Parade; the bandstand itself was not donated by the Kothari family but by the Katraks. The hospital initially was built through a donation by a gentleman named Minocher Homji,” narrates Gadiali.

But over time, the number of Parsis in Karachi has dwindled. Gadiali estimates that the Parsi community has shrunk from about 5,000 at Partition to about 1,200 people now. Much of this decline in numbers is attributed to migration and birth rates.

“Even though Parsi people live long lives, deaths were never replaced by a corresponding number of births,” explains Gadiali. “There was a time when people didn’t get married because there was a lack of housing facilities for them. Now, much of the community-run accommodation facilities are lying vacant.”

While the Parsi community set up trust funds to take care of their own, the community saw major demographic shifts within. In pursuing their careers and sometimes due to insecurity, the younger generations began migrating from Pakistan. The older ones were left behind, sometimes out of necessity and sometimes out of choice.

“It is difficult to travel with an ill parent or parents if you are migrating from Pakistan,” says Gadiali. “There is the obvious tension of travelling, sometimes with kids, handling them, looking for a new home, settling down in a new place and other teething problems. Many people can’t afford to take an ill parent along, because medical costs abroad can be extremely prohibitive.”

It is because of this dynamic that the many of the 30 beds in the hospital are now occupied by elderly people whose families have either migrated or who have nobody to take care of them at home or even those whose families cannot afford caretakers able to tend to them around the clock.

In its essence, the Parsi General Hospital also doubles up as an old home facility. The hospital is a safe space for many Parsi elderly, because a sense of community and belonging pervades the hospital environment. Room rents are minimal in general wards; only Rs300 are charged per day. The maximum daily cost is Rs1,750 for a private ward. Four meals are served to patients every day. Every now and then, some Parsi families also send food and fruits over.

Many families arrange live-in attendants for their loved ones, but those who can’t still rely on the hospital without much hesitation. In the infirmary, for example, an elderly woman in her 90s is taken care of by an attendant around the clock, except at 7pm every evening, when her son arrives from work. The woman’s memory is failing, but what she knows is that her son will have dinner with her every evening.

Life is assisted for many old Parsis but it is normal too; there are no qualms about accepting medical help, nor does it hurt anyone’s ego or sense of self in doing so. Their age brings with it peculiar ailments; the majority admitted on temporary basis have arrived due to fractures, weak muscles, and other orthopaedic complaints. The hospital employs a physiotherapist; he helps patients practice movement exercises and walk.

“We might have a small staff, of doctors and attendants, but what we ensure is that those admitted here will be taken care of. There is an element of trust and reliability involved, since those living abroad need to know that their loved ones are safe,” says Gulbanoo Bamji, joint secretary of the hospital.

From time to time, donations received by various trusts and individuals have allowed the hospital to expand and keep the existing operations running smoothly. Gadiali regrets that it is only a matter of time before none of it will be needed, since there wouldn’t be many Parsis around to begin with.

But for those who live at the hospital, there is much to be grateful about, much happiness to share and many more days to look forward to. There are no regrets of being left behind. There is only an acknowledgment that those in the hospital shall take care of each other, in the best ways possible. This year, they celebrated Valentine’s Day too. They sang songs together, they ate extra snacks too, and they chatted for hours on end.

“All you need is three magical words,” says Aunty Villy, “Thank you God. Thank you for the gift of another day to serve you better. If you run into mishaps, know that ‘this too shall pass.’ Life is what you make it, so make it nice and bright.”

Published on Zoroastrains.net