India’s Parsis search for new funeral arrangements as there are not enough vultures to dispose of bodies

Katy Gundevia spent her final days in an apartment in one of Mumbai’s designated Parsi colonies, a few hundred yards away from the cavernous, circular wells where her community traditionally disposes of its dead.

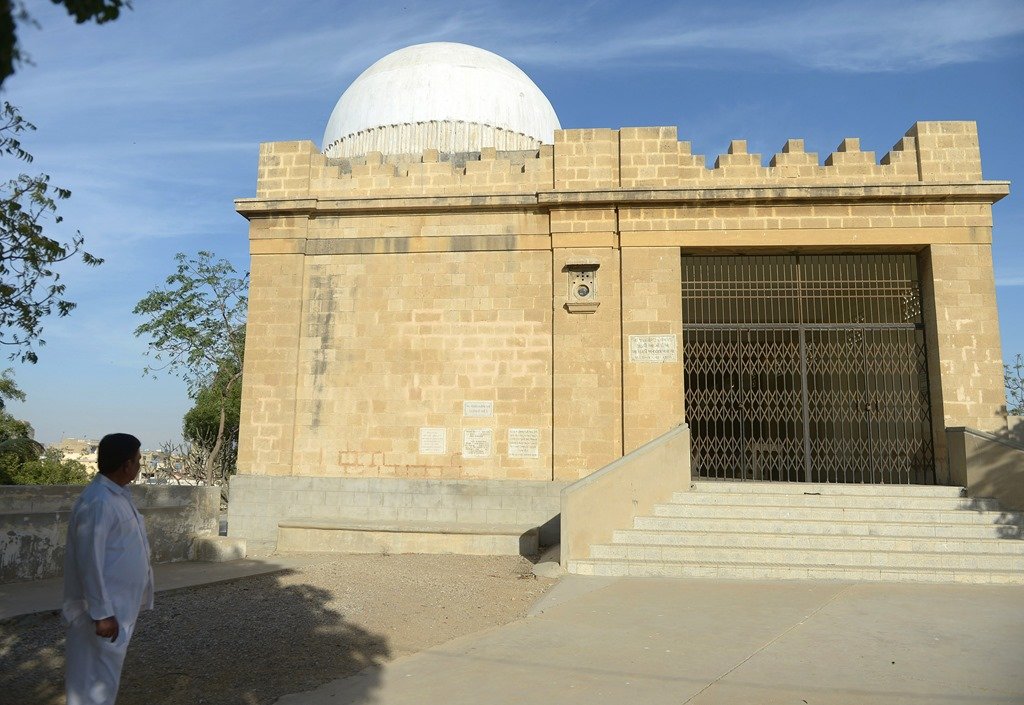

Parsis, descendants of Iranian followers of the ancient Zoroastrian religion who fled to India centuries ago, believe exposing corpses to scavenging birds and the sun ensures the sacred elements of earth, fire and water are saved from pollution by decaying flesh. But despite her strong faith, Ms Gundevia did not want her body to be taken to the nearby stone dakhmas when she passed away.

Parsis, descendants of Iranian followers of the ancient Zoroastrian religion who fled to India centuries ago, believe exposing corpses to scavenging birds and the sun ensures the sacred elements of earth, fire and water are saved from pollution by decaying flesh. But despite her strong faith, Ms Gundevia did not want her body to be taken to the nearby stone dakhmas when she passed away.

Instead, she was cremated on the other side of the city, at a facility used mainly by Hindus, defying hundreds of years of tradition.

Before her death last week, the 82-year-old realised what many of Mumbai’s Parsis have come to accept – that the city’s vultures have disappeared and bodies placed in the dakhmas are now left rotting in the open for months.

“If the system is not working, an alternative has to be found,” said Ms Gundevia’s daughter Navaz Master, who can see for herself how the number of vultures circling not far from the windows of her family home has rapidly declined. The vulture population in India is the victim of poisoning by a bovine painkiller which the birds ingest from feasting on cattle carcasses. “There are days when the smell comes right up to our house,” Ms Master said of the corpses lying in the dakhmas, also known as Towers of Silence.

India’s tiny but prosperous Parsi community is struggling to find a balance between preserving its traditional rituals and an embrace of modern practices, amid a declining birth rate and growing numbers of mixed marriages.

India’s tiny but prosperous Parsi community is struggling to find a balance between preserving its traditional rituals and an embrace of modern practices, amid a declining birth rate and growing numbers of mixed marriages.

Parsis, who are concentrated in Mumbai and count many of the country’s best-known billionaires among their ranks, now number fewer than 70,000 in a country of 1.2 billion, with fertility rates well below average. The debate over their death customs has opened up a divide between liberal Parsis, keen to take their faith forward, and conservatives and elders who have watched with alarm as their community both modernises – and shrinks.

“The vultures are a species threatened with extinction, just like the Parsis” – Dinshaw Mehta, chairman of the Bombay Parsi Punchayet

On Mumbai’s western sea front, Framroze Mirza presides over a newly opened and airy Parsi prayer hall at the crematorium chosen by Ms Gundevia. He was one of two reformist Parsi priests banished by community leaders from the Towers of Silence six years ago for conducting prayers for the few people who chose alternative methods of disposal. Families wanting to bury or cremate their loved ones struggled to find other venues where a priest could perform the ritual four days of prayers required to ensure the soul of the deceased reaches heaven. “This issue split the community,” says Mr Mirza of the dispute which spawned a long-running legal battle and set in motion plans for the new and separate prayer hall.

Mr Mirza and his colleagues are still barred from the Towers of Silence but other priests are, in theory, now allowed to perform prayers at both places, though few have offered their services at the new venue.

Seated under a fan and dressed in an immaculate traditional white suit, the spritely 62-year-old said he saw electric cremation as the fastest and cleanest modern way to dispose of a body, and was upbeat about the future.

“I get so many inquiries about this hall. People keep asking me how they should go about it,” he said. He has conducted seven funerals since the hall opened at the beginning of this month.

Yet for some orthodox Parsis, cremation is not only an affront to age-old traditions, it also has implications for a believer’s spiritual journey. “Every Zoroastrian soul is being condemned by taking this path,” said conservative priest Marzban Hathiram, who is holding meetings to try to dissuade Parsis from doing so. “The reformist section of the community is always waiting for an opportunity to overthrow the system,” he said.

For now, at least, two or three bodies are still committed daily to the original Towers, where solar reflectors have been installed to concentrate the sun’s rays and hasten decomposition. Walking through the acres of lush gardens that house the dakhmas, the head of Mumbai’s powerful community organisation said the future was frightening. “The vultures are a species threatened with extinction, just like the Parsis,” said Dinshaw Mehta, chairman of the Bombay Parsi Punchayet.

At first he opposed the priests backing cremation, but Mr Mehta has come round to the idea that they need to move with the times.

“It’s their choice; each to their own,” he says, resigned to the divisions. “We have accepted that they can pray elsewhere for cremation. But just not here.”